Difference between revisions of "AIM-9E Sidewinder"

(→Description: Added weapon image) |

Colok76286 (talk | contribs) (→Vehicles equipped with this weapon: Added F-4F) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

* {{Specs-Link|f-4e}} | * {{Specs-Link|f-4e}} | ||

* {{Specs-Link|f-4ej}} | * {{Specs-Link|f-4ej}} | ||

| + | * {{Specs-Link|f-4f}} | ||

* {{Specs-Link|f-100d}} | * {{Specs-Link|f-100d}} | ||

* {{Specs-Link|f-104j}} | * {{Specs-Link|f-104j}} | ||

Revision as of 18:28, 14 April 2021

Contents

Description

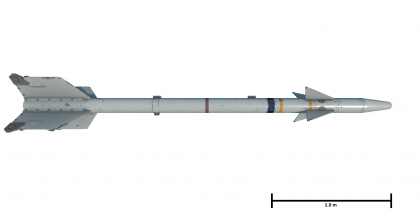

The AIM-9E is an American infrared homing air-to-air missile, it was introduced in Update 1.87 "Locked On".

Vehicles equipped with this weapon

- A-7D

- F-4C Phantom II

- F-4E Phantom II

- F-4EJ Phantom II

- ◄F-4F Early

- F-100D

- F-104J

- Hunter FGA.9

- T-2

- F-1

General info

The AIM-9E is a direct upgrade over the previous AIM-9B missile, and on many aircraft serves as a upgrade over that missile. The AIM-9E provides a missile with a higher top speed and therefore higher energy meaning it is more capable of hitting targets at slightly further ranges and gives the target less time to dodge. The missile features a much larger seeker cone meaning the missile will not lose lock as easily.

Effective damage

Like the -9B, this weapon features a 4.5 kg warhead that will generally destroy an aircraft in one shot providing the weapon scores a direct hit. In some cases the weapon may deal crippling damage such as setting fires or blowing off a wing without necessarily scoring a kill. Not scoring a direct hit will result in greatly reduced damage.

Comparison with analogues

Damage is very similar in practice to almost all missiles of this era.

Usage in battles

Used to engage air targets in all three game modes. The missile is capable of firing from a significant angle around the pipper, but use at the extreme edge of lock on circle will almost always result in a miss.

RB: When the seeker head is primed, a large circle and a small circle will appear. The small circle is the acquisition circle, an enemy plane must be in this circle to be locked, the large circle is the limit of lock, i.e if the target leaves this circle lock will be lost. To give best chances of success this should be used to "lead" a target. e.g a target moving left to right should be placed in the left part of the large circle to give the missile a "head start" in intercepting its target.

SB: The missile is used in a similar sense to the -9B but will be more forgiving and versatile. It can be hard to tell what your limits of lock are but experience will help. To lock place the target in the cross hair while the missile is searching, once the high tone for a lock is heard try place the cross hair significantly a head of the enemy as if making a deflection shot. You must reduce your G loading before firing but not while holding lock. Testing seems to indicate that you must be below 3 or 4G to fire. Like the -9B, the missile works best in surprise attacks and is more resistant to manoeuvres than its predecessor. The missile is great for taking down bombers without dealing with gunners, especially unaware ones. Can easily score a 100% P(k) against AI bombers.

Pros and cons

Pros:

- Mach 2.5 as opposed to 1.7

- Wide seeker head

- Increased effective range

- Decreased time to target

Cons:

- Retains 10G limit

- Has low G limit for launch

- Rear aspect

History

Development

The missile’s history starts at the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) at China Lake in 1947.[1] Under William B. McLean, the missile conception sprang from mating lead-sulfide proximity fuzes that were sensitive to infrared radiation with a guidance system to home onto the infrared source.[2] Initially his own private project, McLean eventually received approval by Admiral William S. Parsons for development.[1]These missiles were first test fired in 1951, with the first air-to-air hit was made on 11 September 1953 on a drone.[3] This experimental missile would be designated as the XAAM-N-7. The missile would also earn the name "Sidewinder" by the development team, named after the desert rattlesnake that senses its prey’s heat and moves in a winding motion.[1][2]

Initially a US Navy project, the US Air Force was urged into participating by Howard Wilcox, the next project lead after McLean was promoted to upper management at NOTS in 1954.[1] This culminated in a shoot-off in June 1955 between the Navy’s Sidewinder against the Air Force’s GAR-2 Falcon missile. The Sidewinder’s performance in this event resulted in the US Air Force putting their support in the Sidewinder.[3] By May 1956, the missile was officially adopted as the AAM-N-7 for the US Navy and the GAR-8 for the US Air Force.[3][4] These designation would remain until 27 June 1963, when the Sidewinder’s designations were standardised across all armed services as the AIM-9.[5]

AIM-9E

While the US Navy improved on the initial production model into the AIM-9D, the US Air Force lagged behind due to development into other projects such as the AIM-4 Falcon.[1] However, the US Air Force eventually came around to improving the AIM-9B Sidewinder missile for their fighters.

Improvements over the AIM-9B came with a reduced drag conical shape, compared to the US Navy's ogival shape in the AIM-9D. Although the upgrades to the optical assembly had a lower frequency rate than the AIM-9D, it had a faster tracking rate.[6] The biggest change to the missile was the implementation of Peltier thermoelectric cooling for the infrared seeker, which eliminated the need of nitrogen gas for cooling in previous models, and can run infinitely so long as electrical power can be maintained.[1][6] These upgrades were implemented into the US Air Force's Sidewinders as the AIM-9E by the late 1960s.[1] 5,000 AIM-9B versions were converted into the AIM-9E.[4] A later improvement in the AIM-9E-2 was also made with a reduced-smoke motor.[3]

The AIM-9E began appearing in Vietnam for the US Air Force sometime after the conclusion of the 1968 Operation Rolling Thunder and became one of their main missile armament. However, intense air-to-air activity in Vietnam were not present until 1972, with the advent of Operation Linebacker. From January to October 1972, there were 71 AIM-9E missile launch attempts. However, only 6 missiles managed to down an aircraft, with 1 other hitting an aircraft. Factors affecting this low performance were put down to "air crew training, launches out of the envelope, the tactical situation, marginal tone, tone discrimination, the missile going ballistic, and other malfunctions."[7]

Due to these results, the US Air Force continued development of the AIM-9 with focus on short-range dogfights against a maneuvering enemy. Initially dubbed the AIM-9E "Extended Performance" missile, the program would be designated as the AIM-9J.[8]

Media

Excellent additions to the article would be video guides, screenshots from the game, and photos.

See also

External links

- References

- Bibliography

- Gervasi, Tom. America's War Machine: the Pursuit of Global Dominance: Arsenal of Democracy III. Grove Press, Inc., 1984.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Falcon & Sidewinder Air-To-Air Missiles." Air Vectors, 01 Apr. 2019, Website.

- Hollway, Don. "The AIM-9 Sidewinder: Fox Two!" HistoryNet, Website.

- Kopp, Carlo. "The Sidewinder Story: The Evolution of the AIM-9 Missile." Air Power Australia, 27 Jan 2014, Website.

- Parsch, Andreas. "AIM-9." Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Designation-Systems.Net, 09 July 2008, Website.

- Parsch, Andreas. "Current Designations of U.S. Unmanned Military Aerospace Vehicles." U.S. Military Aviation Designation Systems, Designation-Systems.Net, 30 March 2020, Website.

- Siemann, John W. Project CHECO Southeast Asia Report. COMBAT SNAP (AIM-9J Southeast Asia Introduction). Defense Technical Information Center, 24 Apr 1974.