Difference between revisions of "AIM-9D Sidewinder"

Colok76286 (talk | contribs) (Edits) |

typenamehere (talk | contribs) (→Pros and cons) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

* Slightly more powerful and much longer burning (2.1 vs 3.5 seconds) rocket motor than the [[AIM-9E]] | * Slightly more powerful and much longer burning (2.1 vs 3.5 seconds) rocket motor than the [[AIM-9E]] | ||

* Has uncaged seeker and good seeker gimbal limits | * Has uncaged seeker and good seeker gimbal limits | ||

| − | * Has a very good | + | * Has a very good 18 G overload |

'''Cons:''' | '''Cons:''' | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

<!--Examine the history of the creation and combat usage of the weapon in more detail than in the introduction. If the historical reference turns out to be too long, take it to a separate article, taking a link to the article about the weapon and adding a block "/History" (example: <nowiki>https://wiki.warthunder.com/(Weapon-name)/History</nowiki>) and add a link to it here using the <code>main</code> template. Be sure to reference text and sources by using <code><nowiki><ref></ref></nowiki></code>, as well as adding them at the end of the article with <code><nowiki><references /></nowiki></code>.--> | <!--Examine the history of the creation and combat usage of the weapon in more detail than in the introduction. If the historical reference turns out to be too long, take it to a separate article, taking a link to the article about the weapon and adding a block "/History" (example: <nowiki>https://wiki.warthunder.com/(Weapon-name)/History</nowiki>) and add a link to it here using the <code>main</code> template. Be sure to reference text and sources by using <code><nowiki><ref></ref></nowiki></code>, as well as adding them at the end of the article with <code><nowiki><references /></nowiki></code>.--> | ||

===Development=== | ===Development=== | ||

| − | The missile’s history starts at the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) at China Lake in 1947.<ref name="Goebel2019">Goebel 2019</ref> Under William B. McLean, the missile conception sprang from mating lead-sulfide proximity fuzes that were sensitive to infrared radiation with a guidance system to home onto the infrared source.<ref name="HollwayFOX2">Hollway "The AIM-9 Sidewinder: Fox Two!"</ref> Initially his own private project, McLean eventually received approval by Admiral William S. Parsons for development.<ref name="Goebel2019"/>These missiles were first test fired in 1951, with the first air-to-air hit was made on 11 September 1953 on a drone.<ref name="ParschAIM9">Parsch 2008</ref> This experimental missile would be designated as the ''XAAM-N-7''. The missile would also earn the name "Sidewinder" by the development team, named after the desert rattlesnake that senses its prey’s heat and moves in a winding motion.<ref name="Goebel2019"/><ref name="HollwayFOX2"/> | + | The missile’s history starts at the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) at China Lake in 1947.<ref name="Goebel2019">Goebel 2019</ref> Under William B. McLean, the missile conception sprang from mating lead-sulfide proximity fuzes that were sensitive to infrared radiation with a guidance system to home onto the infrared source.<ref name="HollwayFOX2">Hollway "The AIM-9 Sidewinder: Fox Two!"</ref> Initially his own private project, McLean eventually received approval by Admiral William S. Parsons for development.<ref name="Goebel2019" />These missiles were first test fired in 1951, with the first air-to-air hit was made on 11 September 1953 on a drone.<ref name="ParschAIM9">Parsch 2008</ref> This experimental missile would be designated as the ''XAAM-N-7''. The missile would also earn the name "Sidewinder" by the development team, named after the desert rattlesnake that senses its prey’s heat and moves in a winding motion.<ref name="Goebel2019" /><ref name="HollwayFOX2" /> |

| − | Initially a US Navy project, the US Air Force was urged into participating by Howard Wilcox, the next project lead after McLean was promoted to upper management at NOTS in 1954.<ref name="Goebel2019"/> This culminated in a shoot-off in June 1955 between the Navy’s Sidewinder against the Air Force’s GAR-2 Falcon missile. The Sidewinder’s performance in this event resulted in the US Air Force putting their support in the Sidewinder.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/> By May 1956, the missile was officially adopted as the ''AAM-N-7'' for the US Navy and the ''GAR-8'' for the US Air Force.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/><ref name="GervasiArsenal">Gervasi 1984, p.256</ref> These designation would remain until 27 June 1963, when the Sidewinder’s designations were standardised across all armed services as the '''AIM-9'''.<ref name="ParschDesignation">Parsch 2020</ref> | + | Initially a US Navy project, the US Air Force was urged into participating by Howard Wilcox, the next project lead after McLean was promoted to upper management at NOTS in 1954.<ref name="Goebel2019" /> This culminated in a shoot-off in June 1955 between the Navy’s Sidewinder against the Air Force’s GAR-2 Falcon missile. The Sidewinder’s performance in this event resulted in the US Air Force putting their support in the Sidewinder.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /> By May 1956, the missile was officially adopted as the ''AAM-N-7'' for the US Navy and the ''GAR-8'' for the US Air Force.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /><ref name="GervasiArsenal">Gervasi 1984, p.256</ref> These designation would remain until 27 June 1963, when the Sidewinder’s designations were standardised across all armed services as the '''AIM-9'''.<ref name="ParschDesignation">Parsch 2020</ref> |

===AIM-9D=== | ===AIM-9D=== | ||

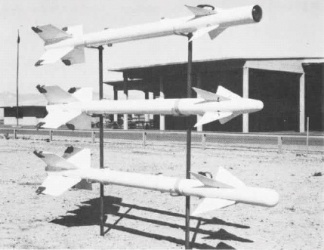

[[File:AIM-9B-9D-9C NAN3-71.jpg|x250px|right|thumb|none|A rack of Sidewinder missiles used by the US Navy. From top to bottom: [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]], [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and AIM-9C.]] | [[File:AIM-9B-9D-9C NAN3-71.jpg|x250px|right|thumb|none|A rack of Sidewinder missiles used by the US Navy. From top to bottom: [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]], [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and AIM-9C.]] | ||

| − | Recognizing the limitations the initial production [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|Sidewinder]] had, the US Navy set to work to improve the missile. The construction of the missile nose was changed into a streamlined ogival nose. The optical seeker was improved with a wider field of view, and the infrared seeker with a reduced field of view to downplay background noise.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9">Kopp 2014</ref> A new nitrogen cooling system was installed for the fuse, which enhanced head sensitivity for the missile.<ref name="HollwayFOX2"/><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9"/> Manoeuvrability was improved with a faster seeker tracking rate, as well as a new actuator system.<ref name="KoppAUSAIM9"/> The Sidewinder's missile range was improved with new Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to have a 18 km range.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/> Finally, a new Mk 48 continuous-rod warhead was fitted to the missile for increased lethality, which also allowed for an infrared or a radio proximity fuse.<ref name="Goebel2019"/><ref name="ParschAIM9"/><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9"/> These improvements were settled into the '''AIM-9D''' variant for the US Navy. About 1,000 AIM-9D units were produced between 1965 and 1969.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/> | + | Recognizing the limitations the initial production [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|Sidewinder]] had, the US Navy set to work to improve the missile. The construction of the missile nose was changed into a streamlined ogival nose. The optical seeker was improved with a wider field of view, and the infrared seeker with a reduced field of view to downplay background noise.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9">Kopp 2014</ref> A new nitrogen cooling system was installed for the fuse, which enhanced head sensitivity for the missile.<ref name="HollwayFOX2" /><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9" /> Manoeuvrability was improved with a faster seeker tracking rate, as well as a new actuator system.<ref name="KoppAUSAIM9" /> The Sidewinder's missile range was improved with new Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to have a 18 km range.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /> Finally, a new Mk 48 continuous-rod warhead was fitted to the missile for increased lethality, which also allowed for an infrared or a radio proximity fuse.<ref name="Goebel2019" /><ref name="ParschAIM9" /><ref name="KoppAUSAIM9" /> These improvements were settled into the '''AIM-9D''' variant for the US Navy. About 1,000 AIM-9D units were produced between 1965 and 1969.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /> |

| − | In 1963, the US Army's Missile Command (MICOM) were interested in the US Navy's development of the AIM-9D and looked into a possible conversion of the missile into a surface-to-air role. The feasibility was seen as possible by 1965 and so the US Army looked into making the AIM-9D the main armament of their ''Chaparral'' program.<ref name="ParschMIM-72">Parsch 2002</ref> These modified AIM-9D Sidewinders were delivered in 1967 and designated ''XMIM-72A'', which were later approved as the ''MIM-72A''.<ref name="ParschMIM-72"/> The only major difference to the missile is that only two of the four fins have rollerons (stabilising gyros), while the other two were made non-moving.<ref name="Goebel2019"/><ref name="ParschMIM-72"/> | + | In 1963, the US Army's Missile Command (MICOM) were interested in the US Navy's development of the AIM-9D and looked into a possible conversion of the missile into a surface-to-air role. The feasibility was seen as possible by 1965 and so the US Army looked into making the AIM-9D the main armament of their ''Chaparral'' program.<ref name="ParschMIM-72">Parsch 2002</ref> These modified AIM-9D Sidewinders were delivered in 1967 and designated ''XMIM-72A'', which were later approved as the ''MIM-72A''.<ref name="ParschMIM-72" /> The only major difference to the missile is that only two of the four fins have rollerons (stabilising gyros), while the other two were made non-moving.<ref name="Goebel2019" /><ref name="ParschMIM-72" /> |

| − | Continual improvements over the AIM-9D version eventually developed into the [[AIM-9G Sidewinder|AIM-9G]] in the 1970s.<ref name="ParschAIM9"/> | + | Continual improvements over the AIM-9D version eventually developed into the [[AIM-9G Sidewinder|AIM-9G]] in the 1970s.<ref name="ParschAIM9" /> |

== Media == | == Media == | ||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

;Bibliography: | ;Bibliography: | ||

| + | |||

* Gervasi, Tom. ''America's War Machine: the Pursuit of Global Dominance: Arsenal of Democracy III''. Grove Press, Inc., 1984. | * Gervasi, Tom. ''America's War Machine: the Pursuit of Global Dominance: Arsenal of Democracy III''. Grove Press, Inc., 1984. | ||

* Goebel, Greg. "The Falcon & Sidewinder Air-To-Air Missiles." ''Air Vectors'', 01 Apr. 2019, [http://www.airvectors.net/avsdaam.html#m5 Website]. | * Goebel, Greg. "The Falcon & Sidewinder Air-To-Air Missiles." ''Air Vectors'', 01 Apr. 2019, [http://www.airvectors.net/avsdaam.html#m5 Website]. | ||

Revision as of 16:51, 20 August 2021

Contents

Description

The AIM-9D is an American Infrared homing air-to-air missile. It was introduced in Update 1.93 "Shark Attack".

Vehicles equipped with this weapon

General info

The AIM-9D is a member of the Sidewinder family of missiles, it incorporates a number of improvements over the AIM-9B, from which it was developed. It should be noted that the AIM-9E was also a development of the AIM-9B rather than the AIM-9D; while the AIM-9D was developed for the US Navy, the AIM-9E was a separate development for the US Air Force. In game the AIM-9D is generally similar to the AIM-9E, but there are distinct differences between the two.

The AIM-9D has the best effective range of any missile currently found on fixed wing aircraft in the game.

Effective damage

Like the AIM-9B & AIM-9E Sidewinders the AIM-9D is fitted with a 4.5 kg TNT warhead and 5 m proximity fuse. This amount of explosive mass is in the vast majority of cases enough to either outright destroy an enemy aircraft or cause non-survivable critical damage; however there are some occasions where an enemy aircraft can survive a hit and make it back to base.

Comparison with analogues

Compared to other Sidewinders

The AIM-9D is a substantial improvement over the AIM-9B. The key improvements are:

- More effective fins

- Overload of 16 G instead of 10 G

- Rocket motor burns for 3.5 instead of 2.1 seconds

- Max speed of 1,000 m/s instead of 800 m/s

- Has an uncaged seeker

- Better IR seeker range

- Seeker gimbal limit of 40° instead of 25°

- Better tracking rate

These changes make the AIM-9D a far superior all round missile. The uncaged seeker makes maintaining a lock prior to launch much easier and allows you to lead the missile. Once the missile is launched it tracks targets much better than the AIM-9B and has far superior speed and range.

The AIM-9D is very similar to the AIM-9E, with the following key differences:

- More effective fins

- Overload of 16 G instead of 10 G

- Rocket motor burns for 3.5 instead of 2.1 seconds

- Max speed of 1,000 m/s instead of 800 m/s

The increased overload and improved fins mean the AIM-9D can track targets better than the AIM-9E. The other changes mean that the AIM-9D has a far superior effective range than the AIM-9E. While both missiles can theoretically fly 18,000 m from their point of launch; the AIM-9D's much longer burning motor and higher maximum speed means that it holds it's speed much better at longer ranges and can remain effective at ranges where the AIM-9E would have lost too much speed to do so. It is not uncommon for AIM-9Ds to be able to hit targets in excess of 5 - 6 km from their point of launch (an even in excess of 7 km some times). However unlike the AIM-9E the AIM-9D cannot be slaved to an aircraft's radar.

Compared to other missiles

Compared to the R-60 the AIM-9D is a very different missile with a different play style. The R-60 has more effective fins than the AIM-9D, a higher maximum overload, and a much higher tracking rate (more than double that of the AIM-9D). All this makes the R-60 a far superior weapon for short range engagements against manoeuvring targets. However, the AIM-9D excels at longer range engagements, being able to engage targets at ranges far beyond what the R-60 could ever hope to, even in ideal conditions. Under ideal conditions the R-60 has a maximum engagement range of around 3.5 km, however in combat the effective range is usually less than 2.5 km; by comparison under combat conditions the AIM-9D routinely take out targets at ranges in excess of 5 km, with even kills on targets as far away as 9 km having been observed in combat. The rocket motor on the R-60 burns for 0.5 seconds less than the AIM-9D, while also producing less than half the thrust, which coupled with it's lower top speed and much lower flight time and flight distance limits severely restrict it's range.

The incredible range of the AIM-9D is what distinguishes it from other air-to-air missiles in the game. It is also among the more manoeuvrable missiles currently available to jet aircraft.

Usage in battles

The AIM-9D is a radical departure from the SRAAM you will have grown accustomed to while playing the Hunter F.6; the SRAAM has far superior manoeuvrability and maximum effective range of an SRAAM is comparable to the bare minimum range you want to be using the AIM-9D at. The AIM-9D is not built for very short range combat; most of the time the missile will not hit it's target when fired from within 1 km, the missile needs to gain speed for the fins to become fully effective, by which point it has usually overtaken its target when fired from this range.

Where the AIM-9D truly excels is in longer range engagements. Ideally you should fire the AIM-9D at a target 2 km or more away from you, and if the target is manoeuvring you should use the uncaged seeker to "lead" the missile (although this starts becoming less important at longer ranges. The AIM-9D has a stated maximum locking distance of 5 km; in practice this means that from the rear you can lock on to most non-afterburning jets at about 4.5 km; however as afterburners produce a lot of heat you can lock on to an afterburning jet as far away as 10 km (and possibly even hit them too).

When engaging a target with the AIM-9D further really is better (to an extent). The more distance the missile has, the better it is able to follow a flight path leading it to the target, and the more likely it is that the enemy will be unaware of your presence. You can routinely engage afterburning targets located 5 - 7 km away from you with the AIM-9D; and although kills at 9 km have been observed you are probably "trying your luck" by the time you get to those sorts of ranges.

At very short ranges (typically a bit less than 1,000 m) the AIM-9D can lock on to an afterburning jet from the front, while this is usually of little use (it cannot really manoeuvre at that sort of range and angle of attack), it can be useful in head-on attacks.

Pros and cons

Pros:

- Good range, can hit targets up to 4 km away from you

- Slightly more powerful and much longer burning (2.1 vs 3.5 seconds) rocket motor than the AIM-9E

- Has uncaged seeker and good seeker gimbal limits

- Has a very good 18 G overload

Cons:

- Cannot be slaved to the radar

- Has a much lower tracking rate than the R-60, making it less effective at tracking targets in comparison

History

Development

The missile’s history starts at the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) at China Lake in 1947.[1] Under William B. McLean, the missile conception sprang from mating lead-sulfide proximity fuzes that were sensitive to infrared radiation with a guidance system to home onto the infrared source.[2] Initially his own private project, McLean eventually received approval by Admiral William S. Parsons for development.[1]These missiles were first test fired in 1951, with the first air-to-air hit was made on 11 September 1953 on a drone.[3] This experimental missile would be designated as the XAAM-N-7. The missile would also earn the name "Sidewinder" by the development team, named after the desert rattlesnake that senses its prey’s heat and moves in a winding motion.[1][2]

Initially a US Navy project, the US Air Force was urged into participating by Howard Wilcox, the next project lead after McLean was promoted to upper management at NOTS in 1954.[1] This culminated in a shoot-off in June 1955 between the Navy’s Sidewinder against the Air Force’s GAR-2 Falcon missile. The Sidewinder’s performance in this event resulted in the US Air Force putting their support in the Sidewinder.[3] By May 1956, the missile was officially adopted as the AAM-N-7 for the US Navy and the GAR-8 for the US Air Force.[3][4] These designation would remain until 27 June 1963, when the Sidewinder’s designations were standardised across all armed services as the AIM-9.[5]

AIM-9D

Recognizing the limitations the initial production Sidewinder had, the US Navy set to work to improve the missile. The construction of the missile nose was changed into a streamlined ogival nose. The optical seeker was improved with a wider field of view, and the infrared seeker with a reduced field of view to downplay background noise.[3][6] A new nitrogen cooling system was installed for the fuse, which enhanced head sensitivity for the missile.[2][6] Manoeuvrability was improved with a faster seeker tracking rate, as well as a new actuator system.[6] The Sidewinder's missile range was improved with new Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to have a 18 km range.[3] Finally, a new Mk 48 continuous-rod warhead was fitted to the missile for increased lethality, which also allowed for an infrared or a radio proximity fuse.[1][3][6] These improvements were settled into the AIM-9D variant for the US Navy. About 1,000 AIM-9D units were produced between 1965 and 1969.[3]

In 1963, the US Army's Missile Command (MICOM) were interested in the US Navy's development of the AIM-9D and looked into a possible conversion of the missile into a surface-to-air role. The feasibility was seen as possible by 1965 and so the US Army looked into making the AIM-9D the main armament of their Chaparral program.[7] These modified AIM-9D Sidewinders were delivered in 1967 and designated XMIM-72A, which were later approved as the MIM-72A.[7] The only major difference to the missile is that only two of the four fins have rollerons (stabilising gyros), while the other two were made non-moving.[1][7]

Continual improvements over the AIM-9D version eventually developed into the AIM-9G in the 1970s.[3]

Media

Excellent additions to the article would be video guides, screenshots from the game, and photos.

See also

External links

- References

- Bibliography

- Gervasi, Tom. America's War Machine: the Pursuit of Global Dominance: Arsenal of Democracy III. Grove Press, Inc., 1984.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Falcon & Sidewinder Air-To-Air Missiles." Air Vectors, 01 Apr. 2019, Website.

- Hollway, Don. "The AIM-9 Sidewinder: Fox Two!" HistoryNet, Website.

- Kopp, Carlo. "The Sidewinder Story: The Evolution of the AIM-9 Missile." Air Power Australia, 27 Jan 2014, Website.

- Parsch, Andreas. "AIM-9." Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Designation-Systems.Net, 09 July 2008, Website.

- Parsch, Andreas. "Current Designations of U.S. Unmanned Military Aerospace Vehicles." U.S. Military Aviation Designation Systems, Designation-Systems.Net, 30 March 2020, Website.

- Parsch, Andreas. "MIM-72." Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Designation-Systems.Net, 20 Feb. 2002, Website.