Difference between revisions of "User:AN_TRN_26"

(Edits.) |

m (Edits.) |

||

| Line 546: | Line 546: | ||

==== General ==== | ==== General ==== | ||

| − | '''Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader''' was born in London, England in 1910. Bader’s father fought in World War I, however, due to injuries sustained in the war, died in 1922. Bader’s mother remarried, however, due to his high energy levels and unruliness, Bader was sent away often to his grandparent's house and later was sent as a border to a prep school. This proved to be what he needed as sports became his outlet for expending energy and competitiveness. Rugby and any other physical confrontations with bigger and older opponents became his go to.<ref name="Hull" | + | '''Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader''' was born in London, England in 1910. Bader’s father fought in World War I, however, due to injuries sustained in the war, died in 1922. Bader’s mother remarried, however, due to his high energy levels and unruliness, Bader was sent away often to his grandparent's house and later was sent as a border to a prep school. This proved to be what he needed as sports became his outlet for expending energy and competitiveness. Rugby and any other physical confrontations with bigger and older opponents became his go to.<ref name="Hull" /> |

| − | At the age of 13, during a holiday trip to visiting his aunt and future uncle, RAF pilot Cyril Burge, Bader was given a tour of an Avro 504 biplane. Although interested in the visit, Bader did not give much thought to becoming a pilot. Bader was accepted to Cambridge and it was at this time that his uncle Cyril Burge let him know of a cadetship offered at RAF Air Force College Cranwell each year for six students. Bader applied and finished in fifth place and at the age of 18, leaving his school early.<ref name="Hull" | + | At the age of 13, during a holiday trip to visiting his aunt and future uncle, RAF pilot Cyril Burge, Bader was given a tour of an Avro 504 biplane. Although interested in the visit, Bader did not give much thought to becoming a pilot. Bader was accepted to Cambridge and it was at this time that his uncle Cyril Burge let him know of a cadetship offered at RAF Air Force College Cranwell each year for six students. Bader applied and finished in fifth place and at the age of 18, leaving his school early.<ref name="Hull" /> |

| − | At RAF Cranwell, officer cadet Bader continued his studies and expanded the types of sports he participated in to include hockey and boxing. Bader also found himself participating in banned activities which included speeding with motorcycles and racing motorcars. His studies lacked, causing him to almost be kicked out not only for grades but for being caught too many times participating in banned activities.<ref name="Hull" | + | At RAF Cranwell, officer cadet Bader continued his studies and expanded the types of sports he participated in to include hockey and boxing. Bader also found himself participating in banned activities which included speeding with motorcycles and racing motorcars. His studies lacked, causing him to almost be kicked out not only for grades but for being caught too many times participating in banned activities.<ref name="Hull" /> |

| − | Having just barely passed, Bader began flight instruction in September 1928 and after just over 11 hours of flight time, he made his first solo flight. Upon finishing flight school Bader was commissioned a pilot officer and was assigned to No. 23 Squadron RAF where he flew Gloster Gamecocks and Bristol Bulldogs.<ref name="Hull" Bader’s competitiveness and thrill-seeking nature led him to perform unauthorized aerobatics with the biplanes, pushing what both he and they could do. In 1931 at an upcoming airshow, Bader and a teammate Harry Day were scheduled to participate in a “Paris” event consisting of acrobatics in competition with another squadron. During a practice session and apparently on a dare while flying a Bulldog Mk. IIA, Bader made a low pass in which his left wing touched the ground causing the aircraft to slam down, pinning Bader in the wreckage. Once pulled free, Bader was immediately taken to the hospital where both of his legs were amputated, one below the knee, the other above.<ref name="Nye" /><ref name="Hull" | + | Having just barely passed, Bader began flight instruction in September 1928 and after just over 11 hours of flight time, he made his first solo flight. Upon finishing flight school Bader was commissioned a pilot officer and was assigned to No. 23 Squadron RAF where he flew Gloster Gamecocks and Bristol Bulldogs.<ref name="Hull" /> Bader’s competitiveness and thrill-seeking nature led him to perform unauthorized aerobatics with the biplanes, pushing what both he and they could do. In 1931 at an upcoming airshow, Bader and a teammate Harry Day were scheduled to participate in a “Paris” event consisting of acrobatics in competition with another squadron. During a practice session and apparently on a dare while flying a Bulldog Mk. IIA, Bader made a low pass in which his left wing touched the ground causing the aircraft to slam down, pinning Bader in the wreckage. Once pulled free, Bader was immediately taken to the hospital where both of his legs were amputated, one below the knee, the other above.<ref name="Nye" /><ref name="Hull" /> |

{{break}} | {{break}} | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| Line 561: | Line 561: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | It took most of a year for Bader to recover from the accident and work to regain many of his former abilities after being fitted for prosthetic legs. Grit and determination learned from early life helped him here as he learned to drive a car, play golf and even qualified to fly again after a trial flight in an Avro 504. While initially, his military medical examination proved him fit, the R.A.F. turned and medically retired Bader.<ref name="Hull" | + | It took most of a year for Bader to recover from the accident and work to regain many of his former abilities after being fitted for prosthetic legs. Grit and determination learned from early life helped him here as he learned to drive a car, play golf and even qualified to fly again after a trial flight in an Avro 504. While initially, his military medical examination proved him fit, the R.A.F. turned and medically retired Bader.<ref name="Hull" /> |

In October 1939, with the threat of war looming and with help from personal friends in the military, Bader was given a second chance to qualify for a flying position. Upon completing refresher courses, Bader was once again medically qualified to fly. Almost eight years after his accident, Bader performed a solo flight in an Avro Tutor and true to form, did the unthinkable to most and turned the biplane upside down flying about 600 feet off the ground. Soon after, Bader trained on Fairey Battle and Miles Master aircraft which were stepping-stones in preparation for flying Spitfires and Hurricanes. | In October 1939, with the threat of war looming and with help from personal friends in the military, Bader was given a second chance to qualify for a flying position. Upon completing refresher courses, Bader was once again medically qualified to fly. Almost eight years after his accident, Bader performed a solo flight in an Avro Tutor and true to form, did the unthinkable to most and turned the biplane upside down flying about 600 feet off the ground. Soon after, Bader trained on Fairey Battle and Miles Master aircraft which were stepping-stones in preparation for flying Spitfires and Hurricanes. | ||

| Line 567: | Line 567: | ||

Bader’s first assignment was to be with No. 19 Squadron which was based out of RAF Duxford. At age 29, Bader was older than most of his fellow pilots. It was here that he got his first look at the legendary Spitfire fighter. Here Bader practised air tactics, formation flying and even flights out over the ocean with sea convoys to practice navigation. Like other pilots such as Alexander Pokryshkin, Bader found that R.A.F. combat doctrine, flying in a line-astern and attacking enemy aircraft singly to be outdated where he preferred to utilise altitude and attacking from the sun to ambush enemy aircraft. He was ordered to learn the R.A.F. doctrine and did so with great skill which aided in his rapid promotion. In June 1940 Bader had his first taste of combat while flying near the coast of Dunkirk at around 3,000 feet. While flying, Bader noticed a Bf 109 flying in front of him heading in the same direction and at about the same speed. It wasn’t long before Bader caught up and downed the 109. Later that day, Bader was also credited with damaging a Bf 110 twin-engine fighter. On his next patrol flight, he was credited with damaging a He 111 bomber and then later while patrolling around allied shipping, almost collided with a Do 17 while firing at the bomber’s rear gunner during a high-speed pass. | Bader’s first assignment was to be with No. 19 Squadron which was based out of RAF Duxford. At age 29, Bader was older than most of his fellow pilots. It was here that he got his first look at the legendary Spitfire fighter. Here Bader practised air tactics, formation flying and even flights out over the ocean with sea convoys to practice navigation. Like other pilots such as Alexander Pokryshkin, Bader found that R.A.F. combat doctrine, flying in a line-astern and attacking enemy aircraft singly to be outdated where he preferred to utilise altitude and attacking from the sun to ambush enemy aircraft. He was ordered to learn the R.A.F. doctrine and did so with great skill which aided in his rapid promotion. In June 1940 Bader had his first taste of combat while flying near the coast of Dunkirk at around 3,000 feet. While flying, Bader noticed a Bf 109 flying in front of him heading in the same direction and at about the same speed. It wasn’t long before Bader caught up and downed the 109. Later that day, Bader was also credited with damaging a Bf 110 twin-engine fighter. On his next patrol flight, he was credited with damaging a He 111 bomber and then later while patrolling around allied shipping, almost collided with a Do 17 while firing at the bomber’s rear gunner during a high-speed pass. | ||

| − | On 28 June 1940, Bader was switched to No. 242 Squadron R.A.F. and became acting squadron leader of a [[Hurricane (Family)|Hawker Hurricane]] unit which was mostly made up of Canadians, a unit which had suffered many losses and was plagued with low morale. Initially resistant of the new commanding officer, the Canadian pilots soon followed their new champion due to his strong personality. With the struggling squadron reactivated and clear to fly, 242 once again became an effective flying unit.<ref name="Hull" | + | On 28 June 1940, Bader was switched to No. 242 Squadron R.A.F. and became acting squadron leader of a [[Hurricane (Family)|Hawker Hurricane]] unit which was mostly made up of Canadians, a unit which had suffered many losses and was plagued with low morale. Initially resistant of the new commanding officer, the Canadian pilots soon followed their new champion due to his strong personality. With the struggling squadron reactivated and clear to fly, 242 once again became an effective flying unit.<ref name="Hull" /> |

| − | On 10 July 1940, the Battle of Britain officially began and Bader’s squadron began to score kills. During inclement weather on one flight, Bader happened upon a Do 17 while only 600 yards out and when reaching approximately 250 yards, the rear gunner opened fire. Bader pressed his attack and fired two bursts into the bomber, which crashed into the ocean, confirmed by the Royal Observer Corps.<ref name="Hull" 21 August saw a similar situation where Bader sent another Do 17 into the ocean. August also saw Bader claim four Bf 110 twin-engine fighters, however during one engagement, he was jumped by a Bf 109 and was almost ready to bail out of his Hurricane but was able to recover the aircraft and limp it back to base.<ref name="Hull" /> | + | On 10 July 1940, the Battle of Britain officially began and Bader’s squadron began to score kills. During inclement weather on one flight, Bader happened upon a Do 17 while only 600 yards out and when reaching approximately 250 yards, the rear gunner opened fire. Bader pressed his attack and fired two bursts into the bomber, which crashed into the ocean, confirmed by the Royal Observer Corps.<ref name="Hull" /> 21 August saw a similar situation where Bader sent another Do 17 into the ocean. August also saw Bader claim four Bf 110 twin-engine fighters, however during one engagement, he was jumped by a Bf 109 and was almost ready to bail out of his Hurricane but was able to recover the aircraft and limp it back to base.<ref name="Hull" /> |

| − | September action slowed a little but Bader claimed several Do 17 and Ju 88 bombers. Sadly, when one of the Do 17 gunners attempted to bail out, his parachute snagged on the 17’s tail wheel and drug him to his death when the aircraft crashed into the ocean. Apparently, Bader took pity on the gunner and tried to kill him to spare him from the rest of the fall, but could not reach him in time.<ref name="Hull" | + | September action slowed a little but Bader claimed several Do 17 and Ju 88 bombers. Sadly, when one of the Do 17 gunners attempted to bail out, his parachute snagged on the 17’s tail wheel and drug him to his death when the aircraft crashed into the ocean. Apparently, Bader took pity on the gunner and tried to kill him to spare him from the rest of the fall, but could not reach him in time.<ref name="Hull" /> |

Starting in March of 1941, Bader received a promotion to acting wing commander and was stationed at Tangmere. This assignment rolled three squadrons under his command, the 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons.<ref name="Nye" /> In an attempt to divide the Germans and keep them fighting on two fronts (Eastern Europe/Russia and Western Europe), Bader’s wing of Spitfire fighters would perform sweeps over German-held territory and what was called “Circus” operations. Circus operations involved utilising medium bombers escorted with Spitfires to perform bombing operations, not necessarily to inflict heavy damage to ground structures, but more to keep the German Luftwaffe tied up trying to repel these attacks. | Starting in March of 1941, Bader received a promotion to acting wing commander and was stationed at Tangmere. This assignment rolled three squadrons under his command, the 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons.<ref name="Nye" /> In an attempt to divide the Germans and keep them fighting on two fronts (Eastern Europe/Russia and Western Europe), Bader’s wing of Spitfire fighters would perform sweeps over German-held territory and what was called “Circus” operations. Circus operations involved utilising medium bombers escorted with Spitfires to perform bombing operations, not necessarily to inflict heavy damage to ground structures, but more to keep the German Luftwaffe tied up trying to repel these attacks. | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 3 July 2019

This page was the 2652nd page created in this wiki. There are currently 25,252 pages and growing. So far betweem 485,586 users (of which 236 are actively editing), 195,549 edits have been made, how many of them are yours?

| Wiki Moderator Since 2018 |

| This member plays War Thunder on Windows |

|

This member considers Yak-2 KABB the best USSR aircraft in game. |

|

This member considers XP-55 Ascender the best USA aircraft in game. |

|

This member considers Fw 190 A-5 the best Germany aircraft in game. |

Contents

Aces of World War II

USA

Bong, Richard I.

General

War Expeirence

Tactics

Media

Bostwick, George E.

General

War Experience

Tactics

Media

Wetmore, Ray S.

General

Raymond Shuey Wetmore grew up in central California amid farm land, the son of a farmer.[1] Growing up Wetmore had the opportunity to take a short ride in an airplane when a flying circus came through, although he was largely unimpressed with the flight. It wasn’t until 1941 when he enlisted into the Army Air Corps that he chose to take the route of a pilot. In 1942 he started flight school as an aviation cadet and graduated in March 1943. With his pilot’s wings, Wetmore was next assigned to the 359th Fighter Group out of England with his first assignment flying P-47 Thunderbolts.[2]

War Experience

One instance Wetmore proved himself as a fighter pilot came when was leading "Red Section" over Merseburg while escorting bombers. During the flight, the bombers were jumped by approximately 30 Bf 109 fighters, reacting to this, Wetmore told his section to drop their external fuel tanks and bank to intercept. The P-51s were travelling too fast to target the Bf 109s who performed a split-ess. While overshooting, this caused the German fighters to split up and made it easier for the American pilots to select and chase a target. Wetmore singled one German fighter out and flew to within 400 meters before he opened fire. Several rounds hit the 109 in the wing root and fuselage and the German pilot reacted by deploying his combat flaps allowing him to slow down and perform a split-ess. Wetmore was in jeopardy of overshooting, however, he was able to make a quick burst into the German fighter which converted into a descending barrel roll which developed into a flat spin of which he did not recover from. As Wetmore was ascending back up to the fray, he was “bounced” or jumped by 15 to 20 Bf 109s at around 6,000 ft. Making a tight turn to avoid the attackers, Wetmore was able to take advantage of the attackers lack of tactics and was able to get behind one where when at a 70° deflection, Wetmore fired a quick burst which all struck the cockpit, apparently killing the pilot as the plane ended up stalling out and tumbling to the ground.[1]

|

Recalling later when his flight came across approximately 100 German Bf 109 fighters..."In order to defend ourselves, we had to attack."[2]

|

Another instance came when flying near Drummer Lake, looking below himself, Wetmore saw a flight of four Fw 190s following in a trail and called out to have he and his wing-man make the bounce on them. Wetmore singled out one of the 190s and at a 20-degree deflection opened fire at 300 meters. The German pilot attempted to extend his gear, however, ended up performing a belly landing which resulted in the destruction of the aircraft and killing the pilot. Selecting a second target, Wetmore gave chase and from very close range, Wetmore fired a short burst and in the 190s attempt to make a break ended up snapping the aircraft into the ground and exploding. Taking on a third target, again within 300 meters, Wetmore opened fire making several positive contacts resulting in the 190 spinning out of control into the ground.[3] Wetmore caught up with his wing-mate and noticed his canopy had frosted over and could not see very well let alone able to make an accurate shot. Both P-51 pilots were able to hit the fourth target with short bursts causing the German fighter to belly land on the snow-covered ground. Wetmore made for a go-around and fired several more shots into the downed fighter causing it to catch fire.[1][2]

The pinnacle of Wetmore's combat achievements happened on 15 March 1945 when he shot down a rocket-powered Me 163.[2] In his own words, he stated: "I dived with him and leveled off at 2,000 ft at six o'clock. During the dive my IAS was between 550 and 600 mph. I opened fire at 200 yards. Pieces flew all over. He made a sharp turn to the right, and I gave him another short burst, and half of his left wing flew off, and the plane caught on fire. The pilot bailed out and I saw the E/A [enemy aircraft] crash into the ground."[4]

Tactics

Wetmore's preferred tactic whether it was in the P-47 or in the P-51 was to get in close behind the enemy and wait for a deflection shot. Typically he would wait until around 300 - 400 meters and pause until the target aircraft would manoeuvre to allow for a 20° - 70° deflection shot. Apparently, Wetmore had exceptional eyesight as during his reports he would recall where his shots landed on the enemy aircraft, specifically noting "wing-root", "cockpit" or "engine."[1]

Situations, where Wetmore and his wingmen were outnumbered, did not deter them from attacking or taking on a numerically superior enemy. Wetmore took the side of divide-and-conquer trying to take on smaller amounts of enemies, however, remained cool under combat when that did not work out and more enemy aircraft jumped into the fight than expected.

Media

War Thunder's Weapons of Victory - Daddy's Girl

-

Ray S. Wetmore (left) converses with his armourer Sgt Locklyn Sangster who is in the process of servicing one of the P-51D's several machine guns.

Ray S. Wetmore (left) converses with his armourer Sgt Locklyn Sangster who is in the process of servicing one of the P-51D's several machine guns. -

Ray S. Wetmore preparing to taxi for takeoff in his P-51 Daddy's Girl.

Ray S. Wetmore preparing to taxi for takeoff in his P-51 Daddy's Girl. -

Ray S. Wetmore being carried from his P-51B after a successful mission by his ground crew.

Ray S. Wetmore being carried from his P-51B after a successful mission by his ground crew.

Germany

Hartmann, Erich A.

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

Marseille, Hans-Joachim

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

USSR

Dolgushin, Sergei F.

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

War Thunder's Weapons of Victory - Dolgushin's La-7

Golovachev, Pavel Y.

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

War Thunder's Weapons of Victory - Golovachev's Yak-9M

Kozhedub, Ivan N.

- Top allied fighter ace, three times Hero of the Soviet Union

General

Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub's first flying experience was as a teenager when he learned how to fly through the local Shostkinsk aeroclub where they flew Polikarpov U-2 (trainer versions of the PO-2) and UTI-16 (two-seat trainer version of the I-16).[5] The "U" in the aircraft name is the Russian uchebny which means "trainer." In 1940 he joined the Soviet military and graduated from Chuhuiv Military Air School in 1941 around the time the German's began their invasion of the Soviet Union. Eager to get to the front, Kozhedub was denied a transfer, instead, his superiors recognized his knowledge and expertise around the aircraft along with his ability to teach and retained him as a pilot instructor.[6] Ivan remained at the school for two more years instructing many pilots who would transfer to the front lines.[5][6] It was during the process of teaching the student pilots that Kozhedub refined his own abilities as a pilot. Finally, in 1943 Kozhedub after several denied requests to go to the front, was granted a transfer to the 240th IAP.

War Experience

Now on the front lines, Kozhedub was provided with one of the new Lavochkin La-5 fighters. In March 1943, Kozhedub flew on his first combat sortie and it would be one that he would not forget, as while focusing on one target, he developed tunnel vision and did not see two Bf 109s which descended upon him and riddled his aircraft with holes.[5] Able to get away, Kozhedub limped his aircraft back to base where it had to be scrapped after he landed. Lessons learned here taught him that you must always look around and keep an eye on the enemy at all times. Religated to older fighters, Kozhedub did not give up and began to increase his tally score of aerial victories as the months went on.[6] Kozhedub exercised confidence and technique and incorporated it with the experience he was gaining. Initially, he started out as part of a squadron, usually working in pairs when going after enemy aircraft, sometimes as bait and other times an attacker. Bomber escort duty was also necessary, but that didn't stop him from adding victory stars to his aircraft. Over time Kozhedub was provided with another new La-5 and several months later he was given an upgraded La-5F and then a La-5FN.[6]

In 1944 as Kozhedub was generating a significant tally of downed enemy aircraft, he was transitioned into the new La-7, which he determined to be the best fighter aircraft in the world and held that belief even after the war.[7] Aerial victory number 55 was especially memorable for Kozhedub, as while he and a partner were flying on patrol, they spotted an unusual aircraft which was travelling faster than what their La-7s could do. The aircraft turned out to be a German jet fighter, the Me 262 which could outrun them. Eager to attempt to shoot down the jet, Kozhedub's partner shot at the jet, spooking the pilot which caused him to turn to the left, right in front of Kozhedub. Losing enough speed in the turn, the jet was an easy target, one which Kozhedub unloaded on, knocking it out of the sky.[7][6] By the time the war had ended, Kozhedub had 64 confirmed aerial victories, however, it is estimated he had over 100, many of those others were shared kills in which he gave the full credit to the other pilot rather than take it for himself.[7]

Preferred Tactics

Kozhedub was a pilot of patience, waiting until almost on top of his target before letting loose his weapons. With nose-mounted cannons in La-5, La-5FN and La-7, setting gun convergence was not necessary, yet, Kozhedub typically waited until he was within 200 - 300 meters before firing and preferred unloading on an aircraft through deflection shooting or by aiming ahead of the target while it was climbing, diving or banking left or right. In an interview with Aviation History magazine, Kozhedub stated that while he respected the courage of German aces, he did not pay much attention to them, instead, he focused on "trying to guess as soon as possible the plans and methods of my enemy, and find weak spots in his tactics."[8]

|

I always felt respect for an enemy pilot whose plane I failed to down.

|

Describing attacking a target, Kozhedub stated, "I chose a victim and came in quite close to it. The main thing was to fire in time."[8] However, it was important to avoid tunnel vision when following a target hence why it was important to maintain caution as "caution is all-important and you have to turn your head 360-degrees all the time", a valuable lesson he learned in his first combat sortie in 1943. "The victory belonged to those who knew their planes and weapons inside out and had the initiative."[8]

Kozhedub spent the early years of the war from 1940 to 1942 as a pilot instructor. While learning to fly always takes time (Kozhedub was required 100 hours of flight time before he was first licensed at the aeroclub) and with the Great Patriotic war heating up, many new recruits were eager to get flying and mastering skills as quickly as possible and as often as eager students tend to do,"...young pilots often ask how they can learn to fly a fighter quickly; I came to the conclusion that the main thing is to master the technique of pilotage and firing. If a fighter pilot can control his plane automatically, he can correctly carry out a maneuver [sic], quickly approach an enemy, aim at his plane precisely and destroy him. It is also important to be resourceful in any situation."[8]

Keeping a cool head and knowing your surroundings were critical for setting up a battle to the attacker's advantage and here, "the main thing was to attack enemy planes during turns, ascents or descents, and not to lose precious seconds..."[8] because any second lost was an opportunity for the opponent to turn the tables and take any advantage away.

Media

Litvyak, Lydia V.

- First female fighter pilot to shoot down an enemy aircraft

- First female ace

General

Lydia Vladimirovna Litvyak, born in 1921 in Moscow and found an early love of aviation where she enrolled in a local flying club at the age of 14.[9][10] By age 15, Litvyak had performed her first solo flight.[11] By the time she was 18, Litvyak had become a flight instructor at the Kalinin Airclub and training 45 pilots by the time the German-Soviet war broke out in 1941.[12] By June 1941 Litvyak applied to join a military aviation unit, however, the recruiter noted that she did not have enough flight hours (1,000 total flight hours were needed) and rejected her application. Undeterred, Litvyak went to the next closest recruiting office and listed her pre-war flight time at over 1,000 hours, thus “meeting” the requirements, she was admitted into Soviet military aviation.[12][10]

After military basic training, Litvyak was assigned to Marina Raskova’s female air combat unit, Air Group 122, which included three regiments, the 586th Fighter Regiment, 687th Bomber regiment along with the famous 588th Night Bomber Regiment (the Night Witches).[11][9][10] Litvyak was assigned to the 586th Fighter regiment where she was selected to and trained on the single-seat Yakovlev Yak-1 fighter aircraft. At the time more advanced fighter aircraft such as the LaGG-3 was reserved for male pilots, whereas the female pilots were allotted the older Yak-1 aircraft.[9]

Litvyak was not a cookie-cutter military recruit and often found ways to express her individuality, including bleaching her hair with peroxide after being required to cut it short and adding a fur collar to her standard-issued military uniform. In spite of her rebelliousness, Raskova determined that Litvyak was a “brilliant pilot with instincts and gifts no training could provide.”[11]

War Experience

Lydia Litvyak’s first opportunity to fly combat patrols started in the summer of 1942 where she and others were assigned to fly defence missions over the city of Saratov, an important city and major port on the Volga River. After a successful assignment, Litvyak and other female pilots were transferred to a male flying regiment near Stalingrad (current-day Russian: Волгогра́д, English: Volgograd).[9] It was here on September 13, 1942, in which Litvyak was pitted in her first dogfight against Jagdgeschwader 53, one of Germany’s most lethal fighter units at the time.[10] It was during this event in which Litvyak shot down her first two enemy aircraft, a Ju 88 bomber and a Bf 109 G-2 piloted by German 11-kill ace Erwin Meier.[11] After Meier was allowed to meet the pilot who shot him down, he was shocked when it turned out to be Litvyak and refused to believe it was her until she explained in great detail the dogfight which lead to his being shot down.[9][12] Upon realizing the truth, he offered his gold watch to Litvyak as a sign of his respect where she stated:

|

"I don’t accept gifts from my enemies."

|

This began a series of successful missions in which she proved herself as a fighter pilot and earned the respect of the other pilots. Over the next few months, Litvyak racked up several more kills both as the sole attacker and shared attacks with fellow pilots of German Ju 88 bombers, Bf 109s and a Fw 190. Opportunities for combat lessened, mostly due to the senior leadership of Litvyak’s flying regiment and so she was transferred to the 9th Guard Fighter Regiment in early January 1943.[12] The men of this unit flew LaGG-3s and so the squadron did not have the facilities to repair the Yak-1 fighters. Coupled with this and the units upgrade to Bell P-39 Aerocobras, the female pilots with their Yaks were moved to the 73rd Guard Fighter Regiment which did have facilities to repair the Yaks.[11] It was here with the 73rd that Litvyak was promoted to Junior Lieutenant. Due to her fierceness in the air and her proven abilities, Litvyak was selected to participate in an experiment dubbed “Okhotniki” or “free-hunter”, an elite aerial fighting tactic which allowed specific pilots to fly in pairs, hunting the skies for enemy aircraft to seek and destroy at will and racked up a few more aerial victories.

In May of 1943, the German artillery was utilizing an observation balloon to report the location of Soviet soldiers, snipers and equipment to German artillery crews on the ground with great success. Attempts were made to destroy the balloon, however, all Soviet fighter attacks which attempted to attack the balloon were repulsed by heavy anti-aircraft fire.[9] Litvyak volunteered to attack the balloon but was turned down. For Litvyak, “no” meant looking for another way to get the job done. This time she approached her flight commander with a plan to fly a wide circle around the active battlefield and attack the balloon from the rear from over German-occupied territory. The plan was accepted and Litvyak took off. The plan worked flawlessly as she was able to come in from the rear of the balloon and get close enough to ignite the hydrogen-filled balloon with her tracer bullets, sending it to the ground in a crumpled heap.[11]

August 1943 proved to be Lydia Litvyak’s final flights where on her 4th sortie of the day on August 1st escorting IL-2 attackers, her flight was attacked by German Bf 109s. Focused on attacking a Ju 88 bomber, Litvyak did not see the two Bf 109s descend on her tail.[11] Another pilot from her flight, Ivan Borisenko recalled, “Lily just didn’t see the Messerschmitt 109s flying cover for the German Bombers. A pair of them dived on her and when she did see them she turned to meet them. Then they disappeared behind a cloud.” Borisenko last saw Litvyak’s Yak through a gap in the clouds which at that time was pouring out smoke and at that point being pursued by as many as eight Bf 109s. When an opportunity presented itself, Borisenko descended below the clouds but did not see her, a parachute or results of an explosion, however, she never returned from that mission.[12][10]

Litvyak was listed as missing in action, however, the full truth is not known. There are accounts of a Yak-1 discovered near the battlefield with a female who had a fatal head wound and was buried in a village nearby, however, there are also accounts of a female pilot parachuting to safety and then captured by German forces. Also listed is an account of fellow POWs recognizing her in a POW camp. Stalin was known to state any Russians taken as POW were considered to be traitors, so it is possible if she was captured, she may have avoided returning to a hostile Soviet Union. To this day there are many speculations as to the end of Lydia Litvyak, but no definite proof.

- Aircraft flown

- Yak-1 - White 02

- Yak-1 - Red 32

- Yak-1 - Yellow 44

- Yak-1 - White 23

- Yak-1b – unknown

Preferred Tactics

Lydia Litvyak, was a fearless pilot who took to the skies in her Yak-1 fighter, an underdog when compared to the German Bf 109s both in firepower and overall aircraft characteristics, never-the-less, Litvyak outperformed even some of Germany’s best.[13] One tactic Litvyak utilised was to attack the bombers, in doing so, this would bring in the escorting Bf 109s which she would then work into a dogfight. Not all fights went in her favour as she brought back to base several heavily beat-up aircraft including one which she had to belly-land. Even when wounded, she opted to get back into a fighter and return to the melee. Litvyak also found success when hunting with a partner and teaming up on enemy aircraft brought down a number of them.[11] It was a combination of instinct and brute force which kept Litvyak fighting even when at against all odds until the end.

Media

Pokryshkin, Alexander I.

- The first pilot to achieve Hero of the Soviet Union three times[14]

- All time highest scoring pilot in an American made fighter (47 kills in a P-39)

General

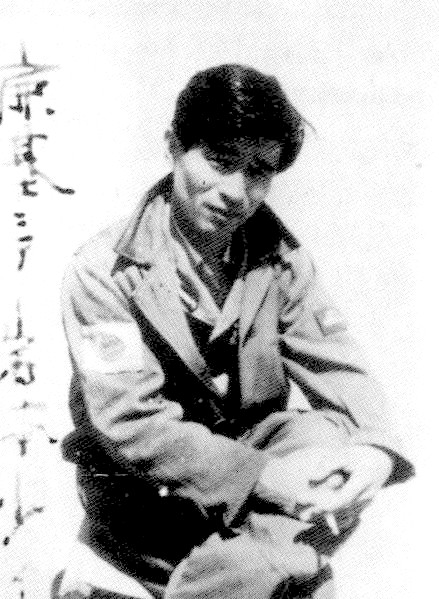

Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin was of Russian ethnicity, born in Novosibisk (Siberia). Pokryshkin’s father was a first generation factory worker and due to not having much money, the family was raised in the poor and crime-ridden part of town.[14] Rather than following the crowd, Pokryshkin followed his own path which noted by his peers as they called him “Engineer”. While at an airshow when he was 12 years old, Pokryshkin developed a fascination for flying. After finishing school, he found work as a construction worker, however, this was not to last very long as in 1930 he left home to attend a technical college where he excelled and earned his degree in 18 months. Finishing this, Pokryshkin then enlisted in the army to follow his dreams and be sent to aviation school. Unfortunately the flight school was closed and all of the cadets were transferred to become aircraft mechanics. Although requests for transfer were made, none were granted.[14]

Determined not to let this drag him down, Pokryshkin decided to put in his all and excel as a mechanic. Graduating from the mechanic school in 1933, he then rose quickly through the ranks and by December 1934 was promoted to Senior Aviation Mechanic with the 74th Rifle Division where he worked until 1938. While working as a flight mechanic, Pokryshkin worked at improving the equipment he worked on which included making improvements to the ShKAS machine guns and the R-5 reconnaissance aircraft.[14] This would ultimately play to his favour later on when higher-ups would try to have him court-martialed. During vacation times, Pokryshkin studied flight manuals and enrolled in a local aeroclub where he learned to fly glider aircraft. During one stint of leave, tested for engine powered aircraft and was able to perform a solo flight and earn his flying license in just under three weeks. Having this flying license automatically qualified him for flight school in which he was accepted.

War Expierence

Pokryshkin’s first assignment took him very close to the battlefront, into Moldavia, June 1941. On June 22nd, the first day of the war, his airfield was bombed, however, he and his aircraft survived without incident. Unfortunately, the next day was his first combat experience which ended in disaster. While patrolling with his squad in MiG-3s, he happened upon an aircraft which he had never seen, taking the opportunity, he opened fire and shot down the aircraft. To his horror, as the aircraft was going down, he noticed the red star on the wings. This aircraft was the new secret Soviet Su-2 light bomber and to prevent his wingmates from shooting down any others, Pokryshkin flew between them and the bombers to prevent any other loss. Pokryshkin was vindicated as the next day he and a wingman were jumped by five Bf 109s where he was able to shoot one down. He scored several more victories, however as luck would have it, he was shot down by German flak behind enemy lines. Pokryshkin spent the next four days working his way back to his base.[14]

|

"One who hasn't fought in 1941–1942 has not truly tasted war".

|

Early on in the fighting, Pokryshkin began to realize that the aerial combat doctrine taught by the Soviets was extremely outdated and he began to take extensive notes of battles and dogfights he and others were going through, looking to find a more efficient and better way to tactically fight.[14] Combat at that time was a treasure trove of information in which Pokryshkin took very detailed notes and ideas to improve over the outdated tactics. Items which he had to factor in were that Soviet pilots were in constant retreat, lacked controlling assistance from HQ and always up against a superior opponent with the odds stacked against them. Pokryshkin had his work cut out for him.[15]

In 1942, Pokryshkin’s squadron was outfitted with the Yak-1 fighter (replacing the MiG-3). Still the underdog against the German Bf 109s, he employed his new tactics with much success. During one light bomber/attacker escort, Pokryshkin was jumped by two Bf 109G-2 “Gustav” fighters. Now separated from his wingman, Pokryshkin attempted to dive away, however realizing the German fighters were faster and heavier, it would only be a matter of time before they would catch up, so he manoeuvred into a chandelle and then barrel-rolled which caused the first Gustav to overshoot, placing him within the Yak’s gunsights. Pokryshkin opened fire and shot the Gustav down. Although Pokryshkin’s aircraft was damaged by the second Gustav, he performed another barrel roll causing the Bf 109 to slide forward into gun range and was subsequently shot down. Pokryshkin proved that a lesser aircraft could outperform a superior aircraft if the proper tactics were employed.[14]

Later during the summer of 1942, the Yak-1 fighters were replaced by the newer lend-lease American P-39 fighters.[14] While not a favourite aircraft of the American pilots and ultimately rejected by the British, the P-39s found a home with the Soviets who put the fighters to good use. The tide was beginning to turn in the Soviets favour as they started to implement Pokryshkin’s tactics which included stacking different aircraft at different altitudes, basically creating a net so that any incoming enemy fighters if attempting to escape would be intercepted by the different layers of Soviet aircraft.[15] Also at this time, ground-based radar, forward controllers and advanced central ground control systems were implemented which were able to help feed real-time information to the pilots in the air and give them a head start on inbound enemy aircraft.

Now outfitted with the P-39K-1s, Pokryshkin once again began to pounce on the Germans. His very first combat flight in the P-39 netted him one Bf 109, however, days later he scored four more and another 8 over the next couple weeks. One of the tactics Pokryshkin learned was that German flights tended to become disoriented and demoralized when the flight leader was shot down and would typically retreat, so he started attacking the flight leader on the initial run into a group. Taking on the most experienced enemy was a difficult task, however with that pilot out of the way it was much easier for his wingmates to go after the rest that did not flee. It was on 23 June 1943 that Pokryshkin traded in his P-39K-1 “White 13” for the now famous P-39N-0 known as “White 100”. White 100 was Pokryshkin’s call sign for the rest of the war and became a call sign feared by German pilots. Transferred down to Ukraine, when escorting Pe-2 bombers, Pokryshkin would break radio silence to announce he was flying and during those times, the Pe-2 bombers performed their tasks without the threat of German fighters because they would not fly “White 100” was in the air.[15][14]

|

"Achtung! Achtung! Pokryshkin ist in der Luft" (English: "Attention! Attention!, Pokryshkin is in the air")

|

Tactics

Pokryskin rewrote the tactical doctrine for Soviet fighters to replace the outdated doctrine he was trained with. It was crucial as a pilot to have advantages which included altitude, speed, manoeuvrability all of which put you behind the enemy to fire on them.[15][14] Even when outclassed and overmatched, tactics could equal the playing field or even transfer the advantage if the pilot knew what they were doing.

|

"The battle training of a fighter pilot, as I see it, is complex process... the formula: altitude, speed, maneuver, and fire."[15]

|

Especially true with the P-39 fighters was the need to be in close when firing as the 37 mm shell had a slower velocity than machine gun rounds and with enough distance could be avoided, in close, it was much more difficult. The new doctrine also included flying with wingmates or squads to allow for watching each other’s backs whether firing at the enemy or just announcing their positions so the wingmates could avoid them. Demoralization was another tactic Pokryshkin employed to great success where he would exclusively target the enemy squad leaders (typically German aces themselves) and eliminate them first. This aggressiveness often caused the enemy fighters to become disoriented or flee the area in retreat. So effective were the tactics, just calling out that “100” was flying in the area kept the Germans from flying that day.

- Aircraft Flown

- MiG-3 - 7

- MiG-3 - 4

- MiG-3 - 01

- MiG-3 - White 5'

- MiG-3 - 67

- Yak-1B - unknown

- P-39K-1 - White 13

- P-39N-0 - White 100

- P-39N-5 - White 100

- P-39D - White 17

- P-39Q-15 - White 50

Media

- War Thunder News: Birthday of Alexander Pokryshkin

- War Thunder Ace of the Month: Alexander Pokryshkin

-

Image of Alexander Pokryshkin standing at the door of a P-39 lend-lease fighter.

Image of Alexander Pokryshkin standing at the door of a P-39 lend-lease fighter. -

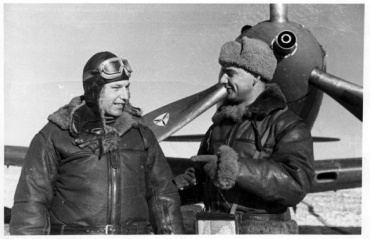

Alexander Pokryshkin and fellow squademate Dmitry Glinka standing before one of their lend-lease P-39 fighters.

Alexander Pokryshkin and fellow squademate Dmitry Glinka standing before one of their lend-lease P-39 fighters.

Zhukovsky, Sergey Y.

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

Great Britain

Bader, Douglas R.S.B.

- British fighter ace who flew with no legs.

General

Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader was born in London, England in 1910. Bader’s father fought in World War I, however, due to injuries sustained in the war, died in 1922. Bader’s mother remarried, however, due to his high energy levels and unruliness, Bader was sent away often to his grandparent's house and later was sent as a border to a prep school. This proved to be what he needed as sports became his outlet for expending energy and competitiveness. Rugby and any other physical confrontations with bigger and older opponents became his go to.[16]

At the age of 13, during a holiday trip to visiting his aunt and future uncle, RAF pilot Cyril Burge, Bader was given a tour of an Avro 504 biplane. Although interested in the visit, Bader did not give much thought to becoming a pilot. Bader was accepted to Cambridge and it was at this time that his uncle Cyril Burge let him know of a cadetship offered at RAF Air Force College Cranwell each year for six students. Bader applied and finished in fifth place and at the age of 18, leaving his school early.[16]

At RAF Cranwell, officer cadet Bader continued his studies and expanded the types of sports he participated in to include hockey and boxing. Bader also found himself participating in banned activities which included speeding with motorcycles and racing motorcars. His studies lacked, causing him to almost be kicked out not only for grades but for being caught too many times participating in banned activities.[16]

Having just barely passed, Bader began flight instruction in September 1928 and after just over 11 hours of flight time, he made his first solo flight. Upon finishing flight school Bader was commissioned a pilot officer and was assigned to No. 23 Squadron RAF where he flew Gloster Gamecocks and Bristol Bulldogs.[16] Bader’s competitiveness and thrill-seeking nature led him to perform unauthorized aerobatics with the biplanes, pushing what both he and they could do. In 1931 at an upcoming airshow, Bader and a teammate Harry Day were scheduled to participate in a “Paris” event consisting of acrobatics in competition with another squadron. During a practice session and apparently on a dare while flying a Bulldog Mk. IIA, Bader made a low pass in which his left wing touched the ground causing the aircraft to slam down, pinning Bader in the wreckage. Once pulled free, Bader was immediately taken to the hospital where both of his legs were amputated, one below the knee, the other above.[17][16]

|

"Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show."

|

It took most of a year for Bader to recover from the accident and work to regain many of his former abilities after being fitted for prosthetic legs. Grit and determination learned from early life helped him here as he learned to drive a car, play golf and even qualified to fly again after a trial flight in an Avro 504. While initially, his military medical examination proved him fit, the R.A.F. turned and medically retired Bader.[16]

In October 1939, with the threat of war looming and with help from personal friends in the military, Bader was given a second chance to qualify for a flying position. Upon completing refresher courses, Bader was once again medically qualified to fly. Almost eight years after his accident, Bader performed a solo flight in an Avro Tutor and true to form, did the unthinkable to most and turned the biplane upside down flying about 600 feet off the ground. Soon after, Bader trained on Fairey Battle and Miles Master aircraft which were stepping-stones in preparation for flying Spitfires and Hurricanes.

War Experience

Bader’s first assignment was to be with No. 19 Squadron which was based out of RAF Duxford. At age 29, Bader was older than most of his fellow pilots. It was here that he got his first look at the legendary Spitfire fighter. Here Bader practised air tactics, formation flying and even flights out over the ocean with sea convoys to practice navigation. Like other pilots such as Alexander Pokryshkin, Bader found that R.A.F. combat doctrine, flying in a line-astern and attacking enemy aircraft singly to be outdated where he preferred to utilise altitude and attacking from the sun to ambush enemy aircraft. He was ordered to learn the R.A.F. doctrine and did so with great skill which aided in his rapid promotion. In June 1940 Bader had his first taste of combat while flying near the coast of Dunkirk at around 3,000 feet. While flying, Bader noticed a Bf 109 flying in front of him heading in the same direction and at about the same speed. It wasn’t long before Bader caught up and downed the 109. Later that day, Bader was also credited with damaging a Bf 110 twin-engine fighter. On his next patrol flight, he was credited with damaging a He 111 bomber and then later while patrolling around allied shipping, almost collided with a Do 17 while firing at the bomber’s rear gunner during a high-speed pass.

On 28 June 1940, Bader was switched to No. 242 Squadron R.A.F. and became acting squadron leader of a Hawker Hurricane unit which was mostly made up of Canadians, a unit which had suffered many losses and was plagued with low morale. Initially resistant of the new commanding officer, the Canadian pilots soon followed their new champion due to his strong personality. With the struggling squadron reactivated and clear to fly, 242 once again became an effective flying unit.[16]

On 10 July 1940, the Battle of Britain officially began and Bader’s squadron began to score kills. During inclement weather on one flight, Bader happened upon a Do 17 while only 600 yards out and when reaching approximately 250 yards, the rear gunner opened fire. Bader pressed his attack and fired two bursts into the bomber, which crashed into the ocean, confirmed by the Royal Observer Corps.[16] 21 August saw a similar situation where Bader sent another Do 17 into the ocean. August also saw Bader claim four Bf 110 twin-engine fighters, however during one engagement, he was jumped by a Bf 109 and was almost ready to bail out of his Hurricane but was able to recover the aircraft and limp it back to base.[16]

September action slowed a little but Bader claimed several Do 17 and Ju 88 bombers. Sadly, when one of the Do 17 gunners attempted to bail out, his parachute snagged on the 17’s tail wheel and drug him to his death when the aircraft crashed into the ocean. Apparently, Bader took pity on the gunner and tried to kill him to spare him from the rest of the fall, but could not reach him in time.[16]

Starting in March of 1941, Bader received a promotion to acting wing commander and was stationed at Tangmere. This assignment rolled three squadrons under his command, the 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons.[17] In an attempt to divide the Germans and keep them fighting on two fronts (Eastern Europe/Russia and Western Europe), Bader’s wing of Spitfire fighters would perform sweeps over German-held territory and what was called “Circus” operations. Circus operations involved utilising medium bombers escorted with Spitfires to perform bombing operations, not necessarily to inflict heavy damage to ground structures, but more to keep the German Luftwaffe tied up trying to repel these attacks.

In the late spring of 1941, the wing’s Spitfires were all being replaced by the newer Spitfire VBs which carried two 20 mm Hispano cannons and four .303 machines guns in the wings. Bader instead opted to fly a Spitfire Mk. VA which did not have the 20 mm cannons, but had a total of eight .303 machine guns. It was his opinion due to his tactics of using a close-in approach that the lower calibre machine guns were more devastating than the 20 mm cannons. Here while flying in France, Bader typically encountered Bf 109s and shot down a handful over the summer as he flew over 60 fighter sweeps through France.

Bader’s last flight occurred on 9 August 1941 while he was patrolling the French coast in his Spitfire Mk. VA looking for Bf 109s. Unlike most days, his typical (and trusted) wingman was sick and could not fly, so Bader flew with three other aircraft from his squadron. Not long after crossing over to France, Bader spotted 12 Bf 109s flying in formation below their position. Initiating the attack, Bader dove, however, his angle was too steep and too fast to realize a gun solution and barely missed colliding with one of the 109s. Pulling up to extend away, Bader levelled out around 24,000 feet but found he was all alone, his wingmen nowhere to be found. Considering returning to base, Bader noticed three pair of Bf 109s several miles ahead of him. Bader dropped down in altitude to gain speed and came up under the 109s, the opened with a short burst from in close, destroying one of the German fighters. He was in the process of attacking a second when it started to trail white smoke and descend and noticed two of the other 109s off of his right, coming at him. He banked away and then believed he had a mid-air collision with one of the other pair of 109s.[17]

The back half of Bader’s aircraft from the cockpit on was gone and his fighter began to rapidly descend in a slow spinning fashion. Knowing he could not stay with the aircraft, he followed the bailout procedure by jettisoning his canopy and releasing his harness pin. The air now rushing into the cockpit started to force him out, however, his artificial leg became trapped in the rudder pedals and would not release. Bader’s only thought was to release his parachute and hopefully pull the leg free. It worked, however, the straps for the artificial leg broke, remaining with the aircraft, however, Bader was free and floating to the ground. Later looking through R.A.F. records, it is believed that another Spitfire pilot mistook Bader for a Me 109, this pilot described in detail of the “Bf 109” whose tail had come off and the pilot bailed out. German records (searched through by Adolf Galland himself concluded that no Bf 109’s had collided that day nor do any of the flight reports – even those of German pilots killed in action matched Bader’s incident). Bader’s artificial leg which was lodged in the aircraft when he bailed out was subsequently found in a field, however, it was badly damaged.

Upon his capture by the Germans, Bader was treated with great respect because of his being a double amputee and a fighter pilot. General Adolf Galland, in an attempt to help Bader, petitioned the British Government safe passage to bring a replacement leg, the operation was approved at the highest level on the German side by Hermann Göring himself. The British responded on 19 August 1941 by sending “Leg Operation” which included six Bristol Blenheim bombers with a good size fighter escort to parachute the replacement leg at a Luftwaffe base in St Omer.[17] Bader spent the next several years a prisoner of war, however every chance he got, he attempted to escape or practised “goon baiting” as the practice was to cause as much trouble to his captors as was possible or to play mind-games with them in an attempt to get them to lose their composure. Bader was ultimately placed in Colditz Castle Oflag IV-C on 18 August 1942 which was determined to be escape-proof. Bader remained here until 15 April 1945 when the United States Army liberated the facility. After his repatriation to Britain, in June 1945 a victory flyover London of 300 aircraft was conducted and Bader was given the honour of leading the entire flight in a Spitfire Mk IX.

Tactics

|

"If you had the height, you controlled the battle...if you came out of the sun, the enemy could not see you...if you held your fire until you were very close, you seldom missed."

|

Bader was a fearless pilot which stems from his thrill-seeking adrenaline junkie attitude he portrayed early on when racing motorcycles and fast cars. He did not have any issues with pushing an aircraft to its limits and was a natural when it came to performing aerobatics. Early on in his career and life, he survived a gruesome low altitude plane crash which resulted in the amputation of both of his legs. Such was his determination that within a year he was back racing cars and flying aircraft to prove he could still be a pilot with the R.A.F. Much of what he learned from racing and aerobatics bled over into his ideas on how to be the best fighter pilot he could be. While he was forced to learn the doctrines of the R.A.F., he never just left it at that and implemented what he learned from combat not only for himself but also for those pilots which flew under his command.

Bader’s philosophy of having altitude, speed and surprise, you could be devastating as a fighter pilot. Several instances during his flying suggested that he flew extremely close to enemy aircraft and at times almost colliding. At one point when attacking a German bomber and realizing he was out of ammunition, Bader contemplated taking out the enemy’s tail rudder with his propeller. With Bader’s preference for in-close fighting (200 – 300 meters), he preferred to have all machine guns on his aircraft instead of a combination of machine guns and autocannons. When his squadron was being upgraded to Spitfire Vb fighters, he chose to retain the Spitfire Va which had eight .303 machine guns as opposed to six .303 machine guns and two 20 mm cannons. It was Bader’s belief that when in close, the eight machine guns could be used with devastating effect.

While most people would think that Bader was at a severe disadvantage being a double amputee, he proved that it actually was a benefit when it came to being a fighter pilot. Without his lower legs, he was able to make tighter turns and maneuvers without suffering the same G-force effects as normal pilots because the blood could only pool so far in his legs and it would take longer and more G-force before he would get to the point of blacking out. In effect his amputation was like later flight suits which would squeeze the pilots legs during high G-force maneuvers, restricting the blood flow to the lower extremities.

Media

-

Douglas Bader posing on his Hawker Hurricane Mk.I in 1940.

Douglas Bader posing on his Hawker Hurricane Mk.I in 1940. - Top-scoring Southern Rhodesian ace of the war, and the highest-scoring ace of Greek origin

-

John Plagis posing in front of his Spitfire Mk IX.

John Plagis posing in front of his Spitfire Mk IX. - Japan's top ace of the Second Sino-Japanese War (war with China 1937 - 1945)

- Shot down 48 F4U Coursair fighters, 1-in-4 of all F4U air-to-air losses in WW II were at the hands of Iwamoto Tetsuzō.

- 1 vs. 1

- Quick Roll: When being followed, begin by skidding sideways to cause a sudden deceleration followed with a 1/2 quick roll causing the attacking aircraft to overshoot, reversing roles of the aircraft, causing the initial target aircraft to become the attacker with a firing solution on the overshot aircraft.

- Corkscrew Loop: When being followed, initiate a loop and attacker will follow, at the top of the loop, begin a skid-roll which will position your aircraft with guns on the attacker aircraft as they are coming up in the loop.

- Yo-yo Turn: This manoeuvre can be performed at either high or low speed and can be used to cause overshoot of an attacker or provide enough spacing for a pursuing aircraft to gain a target solution.

- Causing overshoot: The target aircraft must turn inside the attacking pursuit aircraft, causing the attacker to overshoot, allowing the initial target aircraft to roll onto the initial attackers tail and acquire target solution.

- Preventing overshoot: When an attacker wants to prevent an overshoot of their target, they must perform a quick climb followed with a quick dive, which absorbs energy, but maintains flight path preventing overshoot of the target.

- Formation Tactics

- Two Group Linked Formation Attack: The two groups are divided into offensive and defensive formations. The offensive formation utilises Boom & Zoom and diving attacks against the enemy aircraft while the defensive formations oversee the battle and provide high-altitude cover for the offensive group.

- Rendezvous Attack: Attack enemy aircraft after their mission is over and while they are on the way back to the rendezvous location where they meet up with other aircraft before heading over long distances back to base.

- No.3 Aerial Bomb Attack

- From the 12 o'clock high position, the attacking fighter will invert itself and dive on its target.

- Using an almost vertical dive (60 degrees) is required as the 30 kg No.3 aerial bomb requires releasing at speeds over 280 knots to properly work the timer and arm the bomb for the detonator explosion.

- Due to its excellent flight characteristics, the Zero had to start the dive in the inverted position to allow it to maintain the steep dive angle.

- Fought with famed Normandie-Niémen Hunting Regiment out of Tula, USSR

-

Rene and Maurice Challe in front of White 60, a Yak 9T-37. The Challe Brothers had joined the Normandie-Niemen Regiment on 18 March 1944.

Rene and Maurice Challe in front of White 60, a Yak 9T-37. The Challe Brothers had joined the Normandie-Niemen Regiment on 18 March 1944. -

Rene Challe shares a joke with Kazanov, his Russian Mechanic. In the background is White 60, Challe's personal aircraft carrying the emblem of the French GC HI/7 Fighter Group.

Rene Challe shares a joke with Kazanov, his Russian Mechanic. In the background is White 60, Challe's personal aircraft carrying the emblem of the French GC HI/7 Fighter Group. - ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hess, W. N. (2001). Americas top WW II aces in their own words: Eighth Air Force. St. Paul, MN: MBI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Gaijin. (2015, April 24). [Weapons of Victory] P-51D Daddy's Girl. Retrieved from https://warthunder.com/en/news/3010--en

- ↑ Wyllie, A. (2004). Army Air Force victories. Morrisville, NC: Lulu.

- ↑ Baldridge, C., Fogg, J., & Fogg, R. (n.d.). A Manifest Spirit: The 359th Fighter Group 1943-1945 (1st ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Лицар неба Іван Кожедуб. [Knight of the skies Ivan Kozhedub] (2010.). Retrieved from https://poltava.to/news/3210/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Prominent Russians: Ivan Kozhedub. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/military/ivan-kozhedub/

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bourne, Merfyn (2013). The Second World War in the Air: The story of air combat in every theatre of World War Two. Troubador Publishing Limited. 978-1-78088-677-0. p.263.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Guttmann, J. (2000, September). Interview with Ivan Kozhedub. Aviation History.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 White, E. (2017, October 06). The Short, Daring Life of Lilya Litvyak. Retrieved from https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/10/06/short-daring-life-lilya-litvyak-white-rose-stalingrad/

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Simonovich, S. (2018). Pilot Profile: Lydia Litvyak, the World's First Female Fighter Ace. Retrieved from https://aviationoiloutlet.com/blog/lydia-litvyak-first-female-fighter-ace/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Courtney, C. (2018, October 06). The First Female Flying Ace: Lydia Litvyak. Retrieved from https://disciplesofflight.com/first-female-ace-lydia-litvyak/

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Chen, C. P. (n.d.). Lydia Litvyak. Retrieved from https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=433

- ↑ Thompson, B. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.badassoftheweek.com/litvyak.html

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 Chlon, C. J. (2018, November 01). Site Navigation. Retrieved from https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/innovative-soviet-fighter-ace-2/

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Simha, R. K. (2014, June 07). Alexander Pokryshkin: The air ace who terrorised the Luftwaffe. Retrieved from https://www.rbth.com/blogs/2014/06/07/alexander_pokryshkin_the_air_ace_who_terrorised_the_luftwaffe_35823

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 16.9 Hull, M. D. (2018, December 12). Site Navigation. Retrieved from https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/fighter-ace-douglas-bader-the-rafs-legless-legend/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Nye, L. (2019, January 28). That time the RAF bombed a POW camp with an artificial leg. Retrieved from https://www.wearethemighty.com/history/douglas-bader-replacement-leg-ace?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Aces of World War 2. (n.d.). Ioannis Agorastos "Johnny" Plagis. Retrieved from https://acesofww2.com/rhodesia/aces/plagis/

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Vassilopoulos, D. (2018, October 15). John Agorastos Plagis. Retrieved from https://www.greeks-in-foreign-cockpits.com/pilots-crews/fighter-pilots/john-agorastos-plagis/

- ↑ Alexander, J. H. (2016, April 27). Trial by Fire at Coral Sea. Retrieved from https://www.historynet.com/trial-by-fire-at-coral-sea.htm#

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Généalogie de René CHALLE. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://gw.geneanet.org/garric?lang=fr&p=rene&n=challe

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Donjon, Y. (2007). René Challe. Retrieved from http://chezpeps.free.fr/bruno-challe/@/rene_challe.htm

Plagis, Ioannis "John" A.

General

Born in Hartley, South Rhodesia (current day Zimbabwe) in 1919, Ioannis Agorastos (John) Plagis was born to Greek parents who immigrated from the Aegean island of Lemnos. In 1939 when Britain and German commenced hostilities, John headed to the recruiting station and attempted to volunteer with the Rhodesian Air Force.[18] His application was denied due to the fact that he was still considered a Greek Subject due to his parents being Greek and having been born before the 1923 referendum when Southern Rhodesia became an independent colony in the British Empire. England, however, was desperate for volunteers and accepted Plagis’ application into the Royal Air Force of Britain, beginning service with the R.A.F. in 1940.[19]

War Experience

For Plagis, military training began in Southern Rhodesia, however, he didn’t begin operationally flying until the tail end of the Battle of Britain while based out of Britain. Early operations included flights over France, Holland and Belgium escorting bombers and looking for targets of opportunity. In 1942 an opportunity for Plagis to volunteer to reinforce Malta as they were under constant bombardment from the Germans and Italians. One of the first 16 Spitfires loaded on the H.M.S Eagle aircraft carrier, Plagis and several other fellow colony pilots (one other from Rhodesia, four from Australia, two from New Zealand and eight from England) headed for Malta.[19] Upon their arrival, they went into immediate actions, always outnumbered by enemy aircraft. It was only a matter of weeks before many of the pilots had been killed and most of the aircraft had been lost or badly damaged. England tried several more times to ferry in aircraft and pilots, but fewer were making the journey. Plagis once quipped that “...we at all times fought the enemy with great odds against us, in fact, if four of us were airborne and we encountered twenty enemy fighters and bombers, we considered it a reasonable fight.” In one day during four separate flights, Plagis and three wingmates intercepted and attacked 180 bombers which were escorted by 80 fighters, personally tallying up four destroyed, one damaged and one probably destroyed (not confirmed) without loss of any Spitfires. Total enemy aircraft destroyed while stationed in Malta tallied at 11, with two others probably destroyed and five more damaged.[18]

|

"It is difficult to single out one fighter pilot and make comparisons but because pilot officer Plagis shot down four enemy aircraft, he is worthy of special mention. He flies a Spitfire and with it he is devastating."

|

Plagis was sent back to England where he was found to be malnourished and had both a mental and physical breakdown.[18] After convalescing, he was assigned to No 64 Squadron in Coltishall in Southern England. Here his duties included bomber escort duty and armed recon patrols where he was able to tally up to two more German aircraft shot down. During July 1944, Plagis was promoted to Squadron Commander in charge of No 126 Squadron in which he racked up four more kills. Plagis participated in Operation Market-Garden and during the battle was shot down by anti-aircraft flak over Arnhem. The disabled Spitfire ended up crashing at a high rate of speed, however, Plagis walked away with only minor injuries.[19][18] Later in 1944, No 126 Squadron was upgraded from their Spitfires to Mustang IIIs (essentially P-51B Mustangs) which he flew to the end of the war performing bomber escort.[18] After the war ended, Plagis was sent back to his home country of Rhodesia and continued to serve the R.A.F. there. It wasn’t long until he was called back to England and at the personal request of Lord Tedder, Plagis flew the new Meteor jet aircraft for the next three years. It was at this time he was specifically tasked with giving an exhibition of aerobatics in the jet fighter for various foreign delegations in many city-centres in Europe. In 1948, Plagis received his discharge orders and returned to Salisbury, Rhodesia.[19]

Preferred Tactics

Typically outnumbered while flying in Malta, Plagis learned to rely on wingmates to help balance out air battles where they were at a disadvantage. No time for single glory heroics the Spitfire pilots would work on separating enemy fighters and working them into a position where any of the chase aircraft could line up a firing solution. Teamwork ensured safety with more eyes looking out for enemy fighters trying to sneak into the fight.

Media

War Thunder's Weapons of Victory - Plagis' Spitfire Mk. IXc

Japan

Iwamoto Tetsuzō

Country fought for

Country fought forGeneral

Tetsuzo Iwamoto was born in 1916 and initially grew up in Sapporo, Japan and later moved to Masuda, Japan. Early subjects in school which interested him included mathematics and geometry. Upon graduation at age 18, Iwamoto’s parents suggested he take college entrance examinations. Iwamoto left home, however to his parents' disappointment, they found out that instead he applied for entrance into the Imperial Japanese Navy, passed the examination and had become an Imperial Japanese naval airman 4th class. Five months later, Iwamoto was promoted to 3rd class. In 1936 he again advanced in rank and was a naval mechanic and crewman on the light carrier Ryūjō. It was during this time he studied hard and passed the IJNAS exam allowing him to attend aviator school. Iwamoto passed the flight training program and later a more formal aviation training which lasted through 1937.

War Experience

After graduating from aerial combat training, Iwamoto was assigned to the 13th Flying Group which routinely flew over Nanchang, China. The first opportunity for Iwamoto to participate in combat occurred on 25 February 1938 while escorting Type 96 land-based attack bombers. It was during this time when sixteen Chinese I-15 and I-16 fighters commenced attacking. The first enemy fighter Iwamoto engaged was only 50 m away when he opened fire causing the enemy fighter to ignite and crash. The second target, an I-15 was spotted below him where he descended and pounced on it, causing it to lose control and crash. Next came an I-16 which was at the top of its roll when Iwamoto opened fire, the I-16 was burning and out of control, however, Iwamoto lost sight of it and could only count it as a probable kill. The next I-15 attempted a head-on attack, both aircraft began to climb and dogfight, however, the I-15 attempted to dive away, but this made it an easy target for the Japanese pilot. The final enemy aircraft shot down was an I-16 which was descending with its landing gear extended and at about 200 meters above the ground, Iwamoto opened fire, the I-16 made an immediate split-S manoeuvre, however at that low of an altitude with gear extended, there was no room for error and the I-16 crashed. Iwamoto racked up four confirmed kills in his first aerial confrontation and by the time he was ordered back to Japan, he had flown over 82 sorties and downed a total of 14 enemy aircraft on the Chinese front.

During the battle of Pearl Harbor, Iwamoto was flying the A6M Zero fighter, however, he did not participate directly in the attacks that day. Instead, Iwamoto was chosen to fly “top cover” or security patrols over the carrier group. Due to the violent battle at Coral Sea and the heavy losses endured by the Japanese, they were ordered back to Japan for resupply and in doing so, Iwamoto missed the opportunity to participate in the battle of Midway. Defeat at Midway necessitated Iwamoto returning to service as a pilot instructor to train many new replacement pilots. With pilots trained, Iwamoto was ordered to Rabaul in 1943 where he lead many new and very inexperienced pilots against the Americans, British and Australian pilots of the US Navy and USAAF. During his time at Rabul, Iwamoto filed documentation stating that he shot down over 140 enemy aircraft.

Iwamoto seemed to be like a ping pong ball, going back and forth from Japan to the front lines and back again. In 1944, Japanese forces were removed from Rabaul to Japan, but only for a short time when they were ordered to go to the Philippines. When pulled from the Philippians, Iwamoto was ordered to defend Kyushu and Okinawa, however, the last months of the war, Iwamoto was tasked with training kamikaze pilots.

Iwamoto’s success in the cockpit has been compared to the same strategy of the top Luftwaffe ace pilot, Erich Hartmann where they prefer quick diving attacks with weapons bursts from very close range rather than turning in a dogfight. During the Battle of Coral Sea, US air forces were attacking the Japanese aircraft carrier Shokaku, however, it was here that Petty Officer Iwamoto and a wingman fended off the TBD Devastators, preventing their attempts to torpedo the carrier. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough as Dauntless dive-bombers got through and dropped several 1,000 lb bombs on the carrier deck.[20]

Preferred Tactics

Iwamoto had several tactics he employed depending on the circumstance of the aerial battle:

Media

Ace of the Month - June - Lt JG Tetsuzo Iwamoto

坂井 三郎 Sakai Saburō

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

Italy

Marcolin, Luciano

General

War Expierence

Tactics

Media

France

Challe, René M.P.A.

General

René Marie Paul Alexandre Challe and several siblings learned to love flying and the military at an early age. Their father General Georges Challe was in charge of France's 4th Infantry division during World War I, where he would ultimately die in combat 1917. General Challe's younger brother Maurice Challe was a French aviation pioneer after receiving military flight certification in 1911 as the 46th French military aviator. Maurice died in combat in 1916 while performing missions over enemy territory. Patriotism and heroic stories of General Georges Challe and his brother Maurice inspired the Challe children to pursue careers in aviation and with the military.[21]

Before the start of World War II, René Challe attended military school at St. Cyr and at the Air School in Versailles, upon his 25th birthday Challe received his pilot credentials. Challe would then be assigned to the 3/7 hunting group in the French Air Force. At the beginning of World War II, Challe is promoted to Lieutenant and transferred to 5th group.[21]

War Experience

Challe’s early venture into World War II began after Britain and France declared war on Germany. At the time, Challe had entered into the service of the French Air Force and was part of GC III/7. During the Battle of France, he was assigned to fly an M.S.406, a fighter of French design and build. The 406 was not a stellar aircraft, however, it did have a good climb rate and energy retention allowing for repeated dive and climb situations (Boom & Zoom). This aircraft carried two light-weight 7.5 mm machine guns and a single 20 mm Hispano cannon. As Challe found out, one weakness of the aircraft is its lack of armour. While credited with a potential kill shooting down a He 111, while chasing a Do 17 he was able to disable it causing it to crash, but not before the defensive gunners set his M.S.406 alight and Challe took a bullet to the chest, puncturing his right lung. Upon parachuting to the ground, according to one source, peasants mistook for a Luftwaffe pilot and attempted to kill him. Apparently, it took him slinging insults in French before they realised he was a French pilot evacuated him to Bar-le-Duc to recover in a hospital.[22]

After his recovery, France fell to the Germans and while the military was demobilized, Challe was determined to continue the fight against Germany. In August 1943 in the company of eight other aviators, they attempted to escape through Spain only to be caught and imprisoned. At the end of 1943, they were released to French authorities in Casablanca where they immediately volunteered to serve in the Normandie-Niémen Hunting Regiment which was French pilots flying for the Soviet Union in Soviet-built fighters in the city of Tula. Challe and others began their training on Yak-9 fighter aircraft and he was later assigned to the Yak-9T known as “White 60”. In June 1944, Challe was credited with his first German fighter kill when he downed a Bf 109. In a flight of three Yaks, Challe and his wingmates spotted two Bf 109s, determining they were alone, he dove and came up under one of the 109s and within 100 meters of his target, he opens fire with his 37 mm cannon, shearing off the right wing of the 109, causing it to enter into a spin and crash into the ground. Challe’s wingmates took care of the remaining 109.[22]