From the first operational jet fighter, to bombers intended to be able to fly to America in one trip, Germany’s Luftwaffe pushed the boundaries of military aviation to its fullest extent during the Second World War. However, from the war’s beginning, the Luftwaffe's leader, Hermann Göring, had avidly believed in the power of a certain aircraft type for ridding the skies of enemy fighter opposition: the 'Zerstörer' ('Destroyer'). But what actually was this design, and how successful was it in combat?

A Note on Abbreviations and Units

In the Luftwaffe, different branches were given different names, depending on the role which those aircraft played within the wider force. Bombers were organised into the Kampfwaffe, fighters into the Jagdwaffe, and the 'Zerstörer' into, of course, the Zerstörerwaffe. This was, however, simply a loose term for the different categories into which aircraft and their units would fall, not specific units themselves.

Aircraft were split into Gruppen (Groups), which were split into Geschwaderen (Squadrons), within which would be different Staffeln (Sections). Thus, '1st Staffel of Zerstörergeschwader 26' is commonly abbreviated as I./ZG 26.

The Idea

Since aircraft had first been used for widespread combat (around 1915), the general design and weapon configuration for piston-engined fighters has remained roughly the same: an engine (whether radial or liquid-cooled) at the front, driving a single propellor, with machine-guns or cannons being mounted either on the engine cowling, wings, or through the propellor hub. This set-up was consistently incorporated into propellor-driven fighter designs throughout the 1920s, '30s, '40s, and even into the 1950s; indeed, with this, some of the most successful aircraft ever have been made, such as the Supermarine Spitfire, Bf 109, and P-51 Mustang.

However, during the mid-1930s, a new school of thought in fighter technology started to emerge: what if, instead of fast, nimble, single-seat fighters which had to trade armament for speed, a twin-engined 'Zerstörer' with a much heavier armament for the cost of manoeverability was more efficient against enemy fighter oppostion?

The essential idea of the 'Zerstörer' is similar to a boxing match. In this sport, there are different weight classes: one of the lightest being the Flyweight, and the heaviest the Heavyweight. Now, imagine if one boxer from each of these two weight classes were in the ring against each other. In theory, if the Heavyweight manages to land a hit square in his opponent’s face, he would almost certainly knock him out, or even something worse. Instead of two Flyweights sparring, expending energy and time, the hope was that with one swift blow, a heavy 'Zerstörer' could knock the lighter aircraft out of the sky.

The idea of a 'breakthrough aircraft' had been tested by a few nations after the First World War, however it was in Nazi Germany, mainly driven by Hermann Göring, where the belief in the efficiency of this tactic persisted the longest. Being a successful fighter ace and recipient of the Blue Max (awarded for achieving eight air victories) during WWI, Göring certainly was well-informed on matters regarding military aviation. Clearly, his experience in the last war had shown him the benefits of air superiority, and thus was searching for a way to compete with the rapid advances in fighter technology made in the rest of Europe. For him, the answer was the 'Zerstörer'.

Theories have been put forward that First World War aircraft such as the Bristol F.2 Fighter were the origins for the 'Zerstörer', sacrificing manoeverability for heavy armament. However, the F.2 had its only armament centred in a turret behind the cockpit, the idea being that the pilot could focus on flying and evading enemy fire whilst a dedicated gunner could focus on targets. The Bf 110, in contrast, had more of a traditional, pilot-aimed armament configuration.

So, in 1934, the RLM (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or 'Reich Air Ministry') issued a specification for a multi-engined, long-range bomber-escort fighter, with the capacity for carrying bombs, and armed for offensive operations with cannons. Only three companies came forward to meet the requirement, however Bayerische Flugzeugwerke’s design, the Bf 110, was eventually chosen.

Whilst provisions were made for conversion into a fighter-bomber version (as were all 'Zerstörer' models), the Bf 110's primary role was as a long-range escort fighter, not a fighter-bomber.

Featuring 2×20mm cannons and 4×7.92 mm MGs, the first production Bf 110 (the 'C' variant) was one of the most heavily armed aircraft in Europe at the time. For contrast, the Bf 109's first production variant, the 'B', featured only 2×7.92 mm MGs. It must also be remembered that the 110 (and indeed the 'Zerstörer' idea as a whole) was developed in the age of wooden bi-planes: Britain’s front-line fighter was the Gloster Gladiator; the U.S.S.R.'s was the I-15; Italy’s was the CR.32. Against these lightly armed, slower, and structurally weaker designs, the Bf 110 would have been the king of the skies, being not only faster than the Gladiator (560 km/h, compared to 414 km/h), but having a substantially heavier armament as well. Considering this, the Bf 110 was indeed a very modern design, with an all-metal structure, liquid-cooled engines, cannon armament and radio communication.

In Practice

Poland and Western Europe

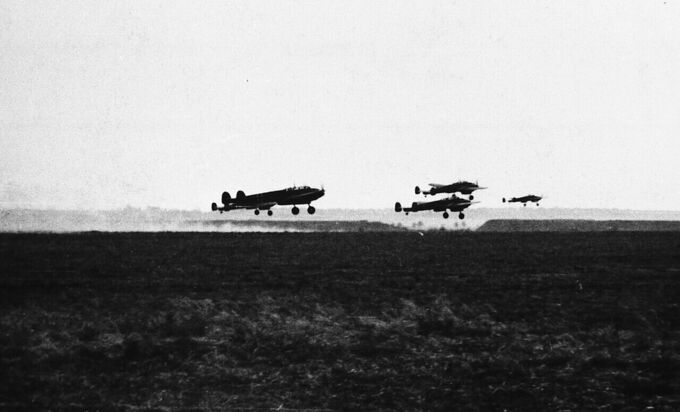

By 1939, tensions on the German-Polish border had increased to such an extent that the Wehrmacht invaded Poland on 1 September. At the time, only 102 Bf 110s were combat-ready. These aircraft were neither organised in Kampfgeschwaderen (bomber units), nor into Jagdgeschwaderen (fighter units), but rather units specific to the 'Zerstörer': the Zerstörergeschwaderen. The Bf 110s performed outstandingly well in this campaign despite their smaller numbers, mainly escorting bombers to their targets, after which they could abandon their responsibilities and strafe Polish airfields. When they did meet enemy fighter opposition, though, they proved more than a match, using 'boom-and-zoom' tactics of diving down on the enemy from in front of the sun (thereby blinding the victim), firing a short burst, and climbing away again. By 6 October that same year, Poland had surrendered, with 'Zerstörer' crews claiming 31 air victories, for the loss of 10.

The experience in Poland had convinced the Bf 110's crews of the efficiency of the 'Zerstörer', and allowed them to enter the Battle of France, Belgium and the Netherlands with great confidence in themselves and their aircraft.

This invasion took place on 10 May 1940, where 145 Bf 110s were comitted to battle in the Netherlands. They partook in ground-attack and escort missions, where they mainly encountered the out-dated Fokker D.XXI and, interestingly, the Fokker G.IA (which was based on similar principles to the Bf 110, but will be discussed later), with some of these aircraft being later employed by the Luftwaffe as trainers for future Bf 110 crews.

The Wehrmacht also undertook the invasion of France (code-named Fall Gelb, or 'Case Yellow') in parallel with the battle for Belgium and Holland. The French Armée de l’Air ('Army of the Air') was an experienced and well-equipped organisation: not only had it seen extensive action in the First World War, producing the top ace of the conflict (René Fonck, 75 kills), but its fighter designs were remarkably modern by 1940, with cannon-armed, highly manoeverable aircraft such as the M.S.406 being front-line fighters. In addition to this, it was reinforced by 25 squadrons of Britain’s R.A.F. (Royal Air Force), consisting mainly of the state-of-the-art Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires, based around Northern France. It was here, in the skies above France, that the 'Zerstörer' crews confidence started to be chipped away: 60 had been lost against R.A.F. and AdlA fighters, such as on 25 May, when around nine Bf 110s were engaged by a large group of Spitfires and Hurricanes. In the ensuing tangle, four 110s were destroyed, and one landed back at base riddled with 59 bullet holes! However, the Zerstörerwaffe was not without victories of its own in this period.

The Bf 110 ace Hans-Joachim Jabs destroyed two Morane-Saulnier 406s within a few minutes of each other on 15th May, and topped this two weeks later with two Spitfire Is in just five minutes on 29 May, ending the campaign with seven kills. Another example of the Bf 110's successes during this period was on 15 May, when III./ZG 26 claimed to have destroyed nine enemy aircraft during a bomber-escort mission, for the loss of two of their own. In reality, however, only two Allied aircraft were lost in that combat, so these 'Zerstörer' claims must always be taken with a certain amount of caution.

The Battle of Britain

The 22 June, 1940 saw the fall of the French government, bringing the majority of Western Europe under Nazi Germany’s control. Their final obstacle in the West, before being able to turn on the U.S.S.R., was Britain. The situation here was a little complex: in order to get an invasion fleet across the English Channel, the Wehrmacht had to first control the skies. If they did not, their dive-bombers would be constantly harassed by enemy fighters, thereby preventing them from performing their vital role: to destroy the Royal Navy, which was alot more powerful than Germany’s, the Kriegsmarine. If the Royal Navy in turn wasn’t defeated from the air, it would be able to crush the Wehrmacht's invasion fleet.

So, in order to gain this air superiority, the Luftwaffe officialy commenced offensive operations over England on 10 July, naming it the Luftschlacht um England (lit. 'Air Battle for England'), also known as the Battle of Britain.

Despite the obvious superiority in speed, manoeverability and climb-rate displayed by the single-engined Bf 109, Göring placed all of his trust in the Bf 110 for winning this campaign, and thus some of the top-scoring and most experienced pilots of the Luftwaffe were drafted into Bf 110 units.

At the beginning of the battle, 278 'Zerstöreren' were ready for operations over Britain, concentrated mainly in Northern France, Belgium and, to a lesser extent, Norway.

At the beginning of the battle, Bf 110 tactics were much the same as previous campaigns: fighter interception, with a bit of airfield ground-attack mixed in afterwards. However, serious problems were soon encountered. Firstly, the idea of a 'long-range' fighter, central to the 'Zerstörer' idea, turned out to be a falsehood in the Bf 110's design, with the aircraft only being able to spend a few minutes in combat over London with enemy fighters, let alone long-distance escort missions. In fairness, it could endure missions for a substantially longer period than the Bf 109's notoriously small fuel capacity. However, it was still a noticable flaw in the 'Zerstörer' Bf 110's design. Attempts were made to overcome this failure, by attaching a 1,050-litre non-jettisonable fuel tank under the aircraft’s fuselage, which crews nick-named the 'Dachelbauch' (lit. 'Dachsund’s belly'), for its low-hanging design.

Though this variant saw limited use (mainly for I./ZG 76 based in Norway, to supply enough fuel to fly to the north-east coast of England), it would prove extremely cumbersome, as not only would it increase drag, but the extra fuel would slosh around inside, altering the aircraft’s centre of mass, making it much harder to fly.

Another problem was that, especially in the late stages of the battle, around September to October, greater emphasis started to be placed on large air raids on towns and cities, using slow, poorly-defended medium bombers such as the He 111 H or Do 17 Z. These would need a heavy fighter escort to defend against the marauding Spitfires and Hurricanes, which would have the range to fly to London and back quite comfortably: obviously, the Bf 110 was chosen for this task. However in this role, the 'Zerstörer' suffered. Units were ordered to keep pace with the much slower bombers, forcing the Bf 110s to fly at medium altitude with their throttle cut back, cruising at a relatively low speed. This would prove fatal, as it meant that 'Boom-and-Zoom' tactics — where speed and high altitude are essential — which were so deadly in the rest of Europe, were out of the question. This put them at a marked disadvantage compared to the Spitfire, which was faster and vastly more manoeverable. In order to combat this, Zerstörer Gruppen would be forced to adopt a tactic specific to vulnerable heavy fighters: aircraft would fly in a rising spiral, covering each other’s tail; this would in theory prevent any enemies from getting on a Bf 110's 'six o’clock' without putting themselves in danger.

This was not always necessarily the case, however, as the combat report of Flight Officer Percy Weaver, 56 Squadron, shows:

“I observed five Me 110s [sic] below in a defensive circle and singled one out for attack. I fired for about six seconds and it broke away […]. I then saw another below me and chased it […] firing a short burst […] it dived vertically into the ground bursting into flames.”

The final factor that caused the 'Zerstörer''s abysmal failure over Britain is related to the previous point: the concept was physically unable to compete with its intended opponents: fighters. When it was presented to the R.L.M., the concept would have easily been able to deal with the wooden bi-planes that equipped most air-forces. However, Göring was unable to see that the R.A.F.'s fighters were not equivalent to wooden bi-planes, and were in fact far superior. Turn-rate, climb-rate, speed and overall agility were much more in the Spitfire and Hurricane’s favour, and to return to the boxing analogy:

A Heavyweight might indeed be able to cause severe damage to the lighter Flyweight. However those punches are useless if he can never catch his opponent, who is always somehow throwing punches from behind him.

A similar scenario occured with the 'Zerstörer' over Britain, and by the end of the campaign, 223 had been lost.

It must be admitted, however, that the Bf 110 was not exactly an easy target during the battle either, with Oberleutnant Jabs claiming 12 victories in under a month from August to September (shooting down three fighters in one day at one point), and Fighter Command’s only Victoria Cross (the highest decoration in the British Army) recipient, James Nicolson, being shot down in flames by a 'Zerstörer' (with his cockpit on fire, he remained in his aircraft long enough to shoot down his victor, who had already counted him as 'written off'. Sustaining severe burns whilst doing so, it was here that Nicolson was awarded the V.C.).

Another example during the battle was on 9 July, when Squadron Leader George Lott of 43 Squadron was caught into a head-on pass with a Bf 110. Bringing all eight of his Hurricane’s 7.7 mm Brownings to bear on the 'Zerstörer', he was caught in a shower of cannon rounds which splintered his canopy into hundreds of shards which flew straight into the Squadron Leader’s face, blinding him and forcing him to land at the nearest airfield. Despite the poor manoeverability and range, the Bf 110's armament still far out-classed that of enemy fighters.

Despite these victories, it was clear that the Bf 110's moment was past, and thus the remaining Zerstörergeschwaderen were mainly relegated to the fighter-bomber role.

An incident of note during this battle was that Göring’s nephew, Hans-Joachim Göring, piloted a Bf 110 in a combat role over Britain. He was shot down and killed in action on 11 July, which further dented the 'Zerstörer''s already sullied reputation.

The end of the Bf 110's 'Zerstörer' role

After the defeat of the Luftwaffe over Britain, the Bf 110 started to be retired from 'Zerstörer' roles, being relegated instead to fighter-bomber, night-fighter and bomber interceptor missions until the war’s end. In the latter capacity especially it performed very well, offering a superior platform for extra weapons (such as Wfr.Gr. 21 rockets or a 37 mm BK 3.7 cannon) compared to the single-engined Bf 109 Gs and Fw 190s, and was able to absorb more rounds as well. On the Eastern Front, the ground-attack role suited the Bf 110 well, with the Knight’s Cross recipient Johannes Kiel destroying 62 aircraft parked on the ground, 29 ground targets, and even a submarine and patrol vessels, illustrating the capabilities of the machine.

This shows how the Bf 110 itself wasn’t a 'bad' or 'out-dated' aircraft; as an interceptor, ground-attack or even night-fighter, it was extremely capable, as were most aircraft of a similair design in such roles. It was, however, how it was originally used, as a 'Zerstörer', that this aircraft struggled in combat.

Thus, by mid-1941, there was a glaring hole in the Luftwaffe’s armoury: a modernised 'Zerstörer' to fill the Bf 110's vacancy.

In 1938, just a few years after the Bf 110 had been designed, Messerschmitt AG began work on another 'Zerstörer' design (possibly in order to iron out some of the 110's deficiencies), in the form of the Me 210. It had a more streamlined bomb arrangement than the Bf 110, and was substantially faster as well. Despite the combat efficiency that this design promised, it was hurried into production before proper testing could be completed, and had been delivered to front-line units by early 1942. Because of this botched process, the aircraft was an utter failure under Luftwaffe markings: it had an unfortunate tendency to stall and go into near-unrecoverable flat spins, and it was difficult to handle due to a short fuselage and wing platform deficiencies. Thus, after some limited combat service in the U.S.S.R., North Africa and France, production was halted just a month after it had begun. Such a failure was this aircraft that it caused great harm to Willy Messerschmitt’s (the head of Messerschmitt AG) reputation, leading Erhard Milch, the Inspector General of the Luftwaffe and an ardent enemy of Messerschmitt’s, to force him to step down as chair of the company. It has even been claimed that Göring remarked, in a fit of rage, that on his grave it would read:

“He would have lived longer if the Me 210 had not been produced.”

Thus, the Bf 110's production was stepped up, being forced to fill in the vacancy left by the 210, and serving as a stop-gap until another design could be put forward to serve in Göring’s Zerstörergeschwaderen.

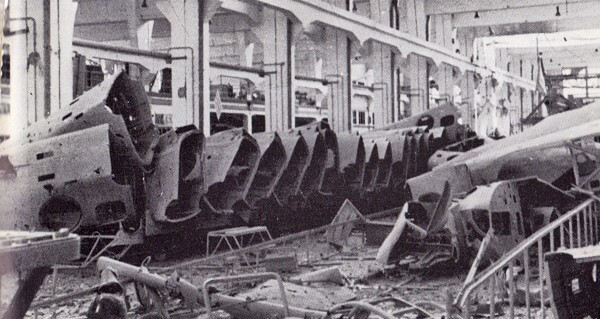

The Me 210 found a new lease of life, however, in the Hungarian Air Force. Denominated the Ca-1 variant ('a' meaning Ausländisch, or 'Foreign') by its German designers, this variant was sold to be assembled under licence in Hungary in early 1943 at the Dunai Repülogépgyár Rt. factory. This variant featured an elongated fuselage, rectifying previous stability issues, and superior Daimler-Benz DB 605 engines.

These aircraft would serve mainly in the fighter-bomber role (although some were experimentally fitted with a 40mm Hungarian Bofors gun for bomber interception, whilst others were used to test a primitive proximity-fuse rocket) from 1943 until they were destroyed by their crews in March 1945. In this capacity as light ground-attack aircraft, the Me 210 Cs were notably successful, despite it not fulfilling a traditionally 'Zerstörer' role.

After the abysmal failure of the 210, the R.L.M. was left again to search for a modern 'Zerstörer', and after a prototype high-altitude Me 310 was built, Messerschmitt settled on the Me 410 to fill the Zerstörergeschwaderen. Design of this aircraft was eased somewhat by the fact that it was essentially an improved Me 210. Adding superior Daimler-Benz DB 603 engines and rectifying previous stability issues, the Me 410 started to replace the aging Bf 110s by January 1943. The intense base armament of the 410 (2×20 mm MG 151 cannon and 2×7.92 mm MG 15s) proved popular with crews, who nicknamed it 'Hornisse' ('Hornet') for the sharp sting offered by its twin 13 mm MG 131 barbettes in the rear.

By this time in the war, however, there was a problem: Germany’s offensive tactics were starting to falter, and the initiative was starting to be handed to the Allies. The Red Army had encircled 22 German divisions at Stalingrad, Voroshilovgrad had been liberated, and Rommel’s hopes in North Africa had been all but crushed. This therefore meant that there was no more possibility for the Luftwaffe to carry out long-range bombing operations in support of attacking ground forces, as there had been earlier in the war; especially if the skies were swarming with superior Allied fighters, as was rapidly becoming the case.

By this time, then, it could be argued that the 'Zerstörer' in the traditional sense, as a bomber-escort, was dead, and those aircraft denominated as such by this time in the war could only carry the name for propaganda purposes.

Such was the case with the Me 410. Never truly used as a fighter, this aircraft (still a wonderful piece of equipment for its time) was resigned to a plethora of other duties. These included ground attack, with a total of three possible bomb configurations; bomber interception, where it saw great success (it could be argued that the 410 was the best bomber-interceptor the Luftwaffe produced) with variants being equipped with a 50 mm autocannon; and in infamous 'intruder' missions over the British isles.

Later War and Influence

So, by the middle of the war, c.1943, the 'Zerstörer' had almost completely disappeared from the ranks of the Luftwaffe, and remained there in name only. This was due to four main reasons:

- The fact that the whole idea was to fail from the beginning, with heavy armament simply not being able to compete with the superior turn rates and manoeverability offered by contemporary mono-engine designs. The 'Zerstörer' thus suffered from poor performance in combat.

- Developing and producing new twin-engined designs was far more time-consuming and costly than simply upgrading already existing designs such as the Fw 190 and Bf 109 G.

- The RLM, spurred on mainly by Hermann Göring, persisted in the belief that the 'Zerstörer' was a valid, competitive design which showed promise in combat well into the war, and subsequently cost the Luftwaffe hundreds of experienced, valuable personnel which it would sorely miss as the Allies' air forces pushed on Berlin.

- Despite it already being

outclassed by 1940, new designs that started to be fielded by the

Allies, such as the P-51 Mustang and La-5, started to completely

outstrip the

'Zerstörer' not only in manoeverability and cheapness, but in heavier

armament as well, which had been the 'Zerstörer''s only saving grace in

the Wehrmacht’s conquest of Europe.

This design, however, was not completely lost on other nations' tactics. The Netherlands designed an aircraft much similar to the Bf 110 in the late 1930s, named the Fokker G.IA. This aircraft shared many features akin to the Bf 110, such as heavy armament (8 × 7.92 mm FN-Browning M.36 No.3s, which earned it the nickname 'Grim Reaper'), a two-man crew, and a split tail (in the Fokker G.IA’s case, in the form of twin-booms). The Dutch even had a name for this kind of aircraft like the 'Zerstörer': 'Jachtkruiser', or 'Hunt Cruiser' in English.

In addition, the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, inspired by the idea of the 'Zerstörer' and probably realising the promise of such a design against the bi-planes and early monoplanes operated by China, initiated a program for the development of such an aircraft in 1937. This resulted in many designs being put forward, however the Ki-45 'Toryū' ('Dragon Slayer', a much better name than 'Zerstörer', in my opinion) was eventually chosen for operational status. It was originally intended to serve in the bomber escort role, much like the Bf 110. Also similar to the Bf 110 was the fact that, upon being faced with the nimble but well-armed fighters fielded by the U.S.A.A.F., namely P-40 'Warhawks', the slower bi-engine simply could not compete, and losses on the Japanese side were usually high. Interestingly, the usage of the Ki-45 after such experiences followed closely the Bf 110 as well, with it first being relegated to ground-attack roles (gaining a good reputation with its crews), and then to bomber-interception, where variants equipped with the large 37 mm Ho-203 cannon could destroy the heavier-armed B-17s and B-29s with ease.

Post-WW2

By the war’s end, in August 1945, the age of the piston engine was nearly over, and the age of jet aircraft was starting to dawn. Germany had already deployed the Me 262 and Me 163 in combat to great success, Britain’s Gloster Meteor had just entered service intercepting V1s, and the U.S.S.R. was busy developing possibly one of the most famous early jets ever, the MiG-15. All these aircraft chiefly relied on speed to come out on top in dogfights, and yet were still able to carry a heavier armament than any piston-engined fighter of the previous war (compare the MiG 15's 2×23 mm NS-23 cannon and 37 mm N-37D cannon to the La-5's 2×20 mm ShVAK cannon), despite having to sacrifice manoeverability. This meant that, in theory, all fighters had become the 'Zerstörer' by 1947, as no longer could an aircraft carry an armament that was markedly heavier than the fighter designs which had already been deployed, without becoming more disadvantaged in combat than it had already been in WW2.

And so the 'Zerstörer' idea died, within a decade of its conception. A folly pushed by a man whose ideas had been stuck in the previous decade, and who had failed to see its doomed future before it had happened.

Gallery

This is somewhat unconventional in these kinds of articles, however I want to share with the reader some images of interest relating to this subject which I have stumbled upon during my research, and which I have found to have enriched my own image of the 'Zerstörer' whilst writing this piece.

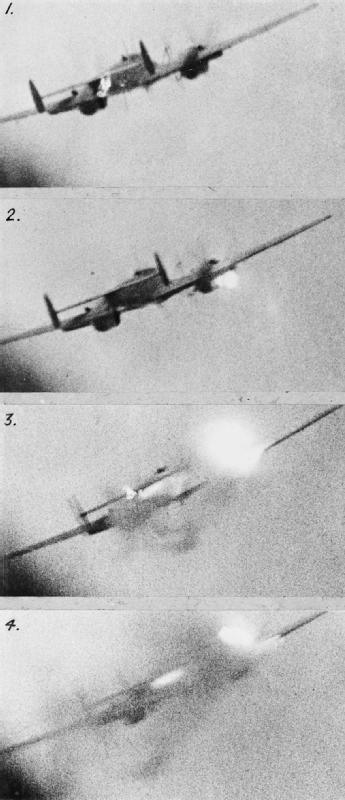

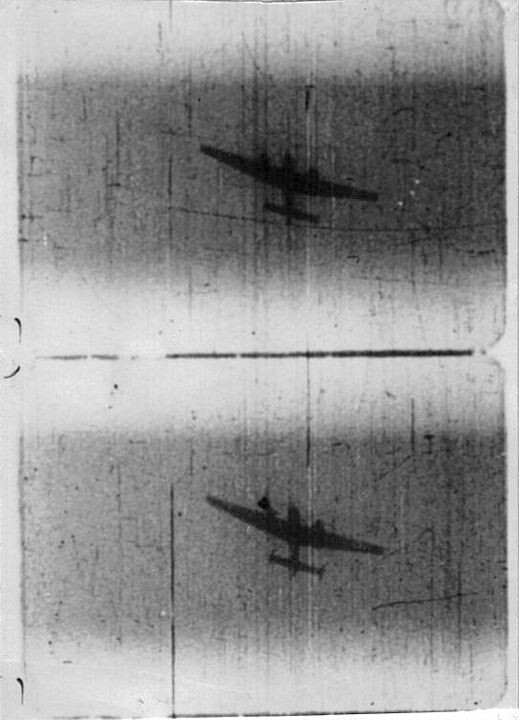

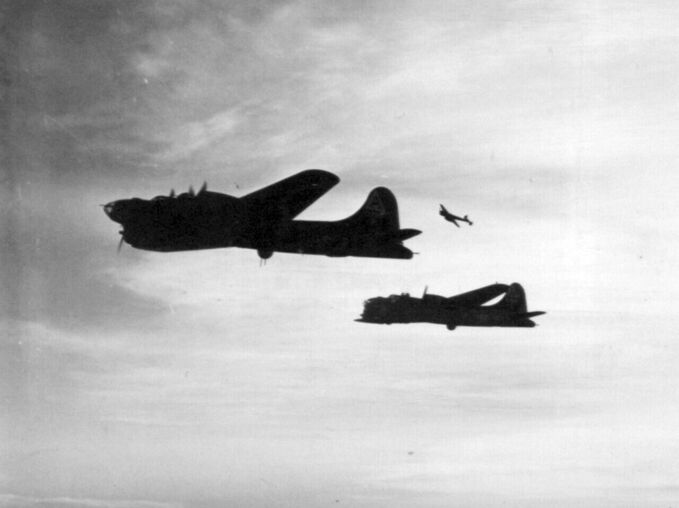

The Bf 110 during the Battle of Britain

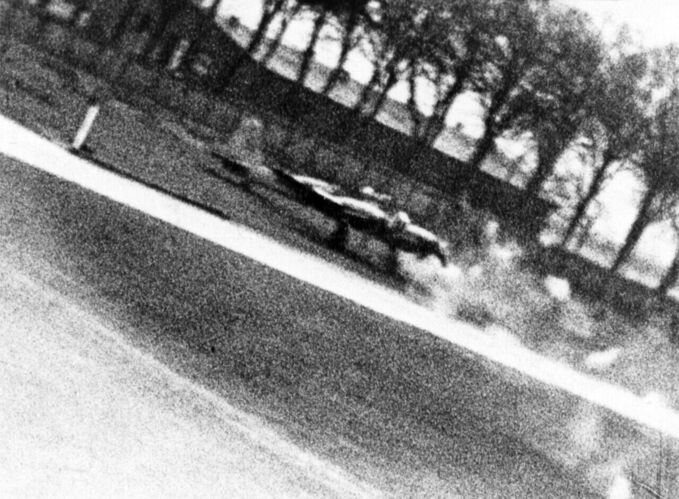

The Bf 110 in the Bomber Interception Capacity

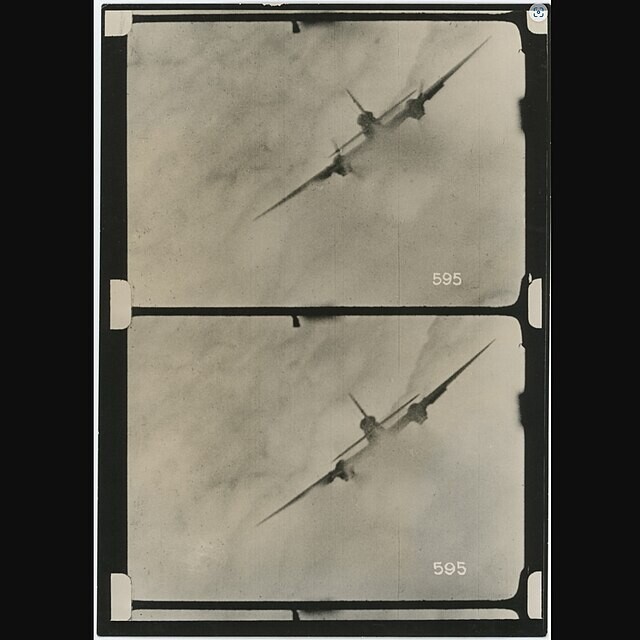

The Me 410/210

- Messerschmitt Bf 110, Wikipedia

- Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zerstörer Aces of World War 2: No. 25 (Aircraft of the Aces) by John Weal, Osprey Publishing

- In Defence of the Messerschmitt Bf 110, Youtube

- 1939-40 (Pt.1) (Aircraft Casualties in Kent) compiled by G.G Baxter, K.A. Owen and P. Baldock, Meresborough Books

- Messerschmitt Me 410 Hornisse, Wikipedia

- Messerschmitt Me 210, Wikipedia

- Kawasaki Ki-45, Wikipedia

- Messerscmitt Bf-110 Part 2: The Polish Campaign, Youtube

- Messerschmitt Bf-110 Part 3: The Western Campaigns of 1940, Youtube

- Luftwaffe Over Britain — Reissue 2019, Key Publishing

- Battle of Britain — Special Commemorative Edition, Time Life

- Battle of Britain 80th Anniversary Issue, Key Publishing

- The Mighty Eighth: Masters of the Air Over Europe 1942-45 by Donald Nijboer, Osprey Publishing

- JACK OF ALL TRADES MESSERSCHMITT’S BF 110, Key Aero Magazine

- Messerschmitt Bf 110 operational history, Wikipedia