Sleek, powerful, and fast, the 'Sparviero' ('Sparrowhawk') was one of the deadliest warbirds above the Mediterranean when it first entered service in the mid-'30s. However, as the Second World War started to go badly for Italy, the SM.79's shortcomings were quickly exposed by a new generation of fighters, which this aircraft’s designers had not prepared for.

A quick note on Italian units:

In the Regia Aeronautica ('Royal Air Force'), aircraft were split into Squadriglie (the equivalent of an R.A.F 'Squadron') of roughly 16 machines each. There were two Squadriglie to each Gruppo (the R.A.F.'s 'Group'), and roughly two Gruppi to every Stormo. The Stormi, depending on the role of the aircraft within the unit, were given an abbreviation; in the case of the 'Sparvieri' Stormi, this would be B.T., or 'Bombardamento Terrestre' ('Land Bombing').

Origins

It could be argued that the 1930s was the Golden Age of aviation in the West, with fighter technology constantly improving and aviation increasingly being used for leisure and in races. Of these innovations, many were popularized in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, both of which had shown great interest in aviation in the post-war period. This was especially true for the concept of widely available civilian passenger airlines, another new idea in this period. In fact, many famous aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica and Luftwaffe (most of which are featured in-game) were originally designed with passenger transportation in mind: think the Do 17, He 111 (although this is debatable), and the SM.81 'Pipistrello'. It was with this in mind, as a commercial airliner, that Savoia-Marchetti initiated the development of one of the most famous Italian aircraft of the war, the SM.79.

Design and Developement

By late 1933, Savoia-Marchetti’s chief aeronautical engineer, Alessandro Marchetti, had produced the plans for this new aircraft. His priorities in the design had mainly been speed and maneuverability, as it was intended not only as a commercial airliner but also as a racing plane for international races such as the Istres-Damascus-Paris (where the SM.79 came first) and MacRobertson England-Australia race (however, it entered production too late to compete in this). Its overall structure was inherited from the earlier SM.81, following the vogue at that time for 3-engined aircraft (as can also be seen in the Ju 52 and Ford Trimotor). However, unlike the 'Pipistrello, ' the SM.79 was designed with a retractable undercarriage, which at that time was rather a novelty, especially amongst Italian designs.

The focus on speed in this aircraft is apparent in the design: the fuselage was noticeably light, consisting of a welded steel tube frame covered in fabrics and duralumin, while the wings were constructed using wooden wing spars. While this was an outdated method for aircraft assembly by this time, the lightness of its frame and wings was noticeable, while it was still able to retain durability. In addition, the lightness afforded by the structure allowed for the aircraft to remain afloat in an emergency landing for 30 minutes before sinking, allowing the crew ample time to get out safely.

The first prototype, coded I-MAGO, was fitted with three Piaggio P.IX Stella RC2 nine-cylinder radial engines. With this configuration, it flew from Milan to Rome in June 1935 in 1 hr. 10 min. with an average speed of 408 km/h. However, it was soon realized that the Piaggio engines were not only not providing enough power to allow the SM.79 to perform at its fullest potential but also were unreliable and so were replaced numerous times until finally an installation of three Alfa Romeo 126 RC.34s was settled on.

By now, the SM.79's prototype had excelled in many races and competitions and was one of the best designs Italy could offer in the world of aeronautical racing. So successful was it that it broke 26 world records. Because of this, increasing interest in the project was shown by the Regia Aeronautica, who were quick to spot its promise as a medium-long-range bomber. After an official inspection of the aircraft, Savoia-Marchetti built another prototype solely for military interest, which was then set a test: in September 1935, it was to fly 2,000 km, weighted with 2,000 kg to simulate the burden of a full payload, defensive armament, etc.

Having completed this challenge successfully (with an average speed of 386 km/h and breaking six world records at the same time), full-scale production of the SM.79 was authorized to begin.

Originally, two variants were produced: one for commercial use (racing and transport) and one for the Italian Air Ministry’s testing; however, production of the civilian variant was eventually dropped, and the SM.79 was then adopted by the Regia Aeronautica for military operations in early 1936, given the name 'Sparviero' for its clean lines and remarkable speed.

Overall, not many changes were made to the SM.79 series 1 (the first fully military variant), apart from:

- The introduction of 5x defensive machine guns, consisting of one fixed, forward-facing 12.7 mm Breda-SAFAT machine gun, one mounted dorsally, one mounted underneath, and 2x license-built 7.7 mm Lewis guns in the waist.

- Due to the third engine on the nose, the traditional position for the bombardier at that time (at the front of the aircraft, usually inside a greenhouse-like canopy) was unavailable. Thus, a position for the bombardier was added in a ventral gondola, with a Jozza-2 bombsight and automatic camera.

- A bomb-bay and cat-walk with the capacity of holding 1,250 kg of explosives was also added.

Even after these modifications, the 'Sparviero' was much faster than any of its peers, with a maximum speed of 430 km/h. In comparison, the Do.17, Germany’s equivalent medium bomber, could go only 407 km/h, and had a lighter maximum bomb load as well.

In Action

Spain, 1937-1939

Having begun production of the SM.79 in October 1936, Italy now needed somewhere for this aircraft to receive its baptism of fire and test it in combat. The answer: Spain, which was fighting a vicious civil war.

Both Germany and Italy were already supporters of the Nationalist cause, which was led by General Francisco Franco; indeed, the Aviación Nacional ('National Air Force') already had Italian BR.20s, SM.81s and CR.32s, as well as German Do 17s and Bf 109s in service. So, in early 1937, more aircraft designs arrived for the Francoist cause, this time in the form of the 'Sparvieri'.

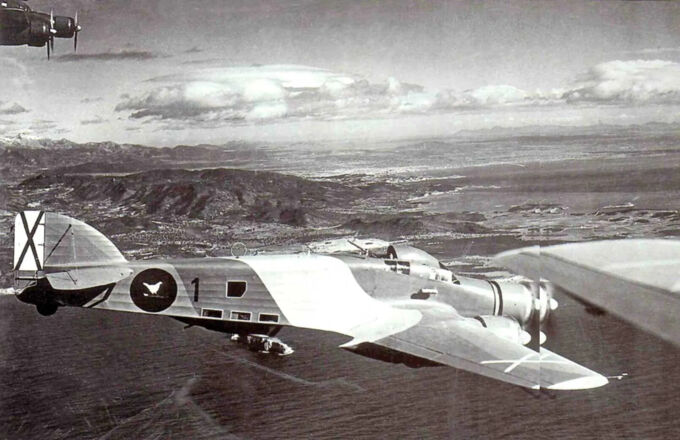

Originally, only three aircraft of the 12° Stormo B.T. (known as the 'Sorci Verdi' or Green Mice) were sent, however it was later joined by the 111° and 8° Stormi. Based in the Balearic Isles as four separate groups known as the Falchi delle Baleari ('The Balearic Falcons'), these aircraft were used mainly for attacking and weakening the Republican naval blockade in the Straits of Gibraltar, and 5 'Sparvieri' took part in the sinking of the battleship Jaime I at Cartagena on the 21st May 1937, causing some damage by dropping sixty 100kg bombs.

Cities too were struck by SM.79 units, notably during the infamous raid on Guernica on 27th April 1937, or when a lone 'Sparviero' disabled the power station of Seira. Ground-attack duties were generally left to the slower SM.81s, who were provided with an escort; the SM.79s, however, operating at higher altitudes and higher speeds, didn’t need fighter cover, as not only could no enemy fighter catch them, but no friendly aircraft could keep up with them either!

On the 11th of October, 1937, three SM.79s were intercepted by a group of Soviet-made Polikarpov I-16s. The 'Moscas' ('Flies, ' a nickname given to the I-16), being one of the few monoplane fighter designs in service with the Republican Air Force, were the only aircraft that were able to keep pace with the 'Sparvieri', going only 15 km/h faster, despite their smaller size. During the engagement (which was the first instance of combat for the SM.79), one bomber was damaged, and none were lost, showing the near-invincibility of the 'Sparviero' in the skies above Spain.

By the end of the conflict in 1939, the SM.79 had shot down 19 Republican aircraft for the loss of 4 of its own, participated in the destruction of a battleship, and had dropped nearly 6,000,000 kg of bombs.

The new fascist government retained 61 of the 100 SM.79s (mainly the serie 1 variant) that had served during the war, as well as buying 26 more.

Overall, the experience gained in the Spanish Civil War regarding the SM.79 would prove invaluable to the Regia Aeronautica, with a greater understanding of its flight characteristics and limitations (such as a lack of oxygen masks), allowing for important improvements in future models. In addition, it gained great popularity with its crews, who affectionately named it 'Il gobbo maledetto' ('The damned hunchback'), due to its distinct dorsal hump. Furthermore, the operations over Spain convinced the Regia Aeronautica that fast, high-altitude bombers could simply outstrip enemy interceptors and so didn’t require fighter escort; this overconfidence in its abilities would prove fatal, however, in the next war in which the 'Sparviero' was to fight.

The Second World War

By the time Italy entered the war on the 10th of June, 1940, the Regia Aeronautica had 403 combat-ready 'Sparvieri' divided into fourteen Stormi, making up the bulk of Italy’s bomber strength.

France, 1940

By the 12th of June, as Germany was unleashing its Blitzkrieg upon a shocked France, Italy decided to share in its destruction, mainly as a token of allegiance to Nazi Germany, but also as a chance to expand her Mediterranean influence. It was under these circumstances that the SM.79 had its first taste of combat during the Second World War. Both that day and the following, 19 'Sparvieri' of the 9° and 46° Stormi (based at Viterbo and Pisa, respectively) set out to attack French shipping on the southern French coast, along with the Sardinian-based 38° Gruppo, which attacked the French naval base of Bizerte in Tunisia.

With the southeast of France coming under Italian control on June 24th, Italian High Command turned its attention east, towards Greece and the Balkans, with the aim of further extending its Mediterranean seaboard.

Greece, 1940

Thus, on the 28th of October, the first units of the Regio Esercito ('Royal Army') crossed the Greek border in the north of the country. Supporting this offensive were the 104° and 105° Gruppi based at Tirana, Albania, as well as other SM.79-equipped units based in the Aegean Sea, such as the 92° Gruppo, which operated from Gadurrà airfield in Rhodes. From these bases, the 'Sparvieri' were deployed in a multitude of roles, as troop transports, air support for the faltering infantry columns, and torpedo bombers against Greek shipping (this role in particular will be discussed in more detail later). Despite the Regia Aeronautica’s best efforts, however, this campaign would turn out to be an utter fiasco for Italian forces, with the last units being withdrawn from this front on the 22nd of April, 1941.

North Africa and Ethiopia, 1940-1942

Mussolini’s next attempt at expansion was in North Africa, with the invasion of Egypt on the 13th September.

125 SM.79s divided amongst 4 Stormi were sent at first to Libya but were eventually joined by the 27° Gruppo, based in Barce, in what is now Libya. In this theater, the SM.79 carried out the tasks that it had done so well in the past: border patrols, long-range bombing, ground attacks, and transport duties. However, the confidence in the aircraft’s abilities, which had been built up through years of weak opposition, was quickly shattered by the RAF’s Spitfires and Hurricanes.

This came as a great surprise to the crews of the SM.79: their only previous experience with the RAF had been in Ethiopia just a few months before (where 84 'Sparvieri' were sent to support the attacking ground forces). In this conflict, the Italians were intercepted mainly by the antiquated Gloster Gladiator or even the South African Hawker Hartbee. Thus, unlike the Luftwaffe, which had already encountered the Spitfire and Hurricane in France, the Regia Aeronautica was caught completely off-guard by these new British designs.

Early in this campaign, the SM.79s would perform their attacks in much the same fashion as they had had done in Spain, with minimal fighter cover. However, the key difference now was that the heavier-armed fighter opposition that faced them could keep pace with the 'Sparvieri', and were indeed much faster than them. Thus, when contact was first made with this new generation of fighters, losses were heavy on the Italian side, and these bomber formations started to carry out raids whilst accompanied by some sort of fighter cover, mainly in the form of MC.200s and MC.202s. Despite this, most units were withdrawn after the defeat of the Italian forces in North Africa in early December, in order to focus on Malta and the Mediterranean convoys, although some were retained to support the German Afrika Korps' efforts in the Western Desert, notably during the battles of El Alamein. For the aircraft that remained in this theatre, the situation only got worse with the introduction of the Lend-Lease program in March 1941: suddenly, not only had the (already deadly) machine gun-armed Spitfires received 20mm Hispano cannons, but faster, newer American designs such as the P-38, P-51 and P-40 were posing a threat to the near-defenceless 'Sparvieri'.

Yugoslavia, 1941

Thirty SM.79s were used in the Axis assault against Yugoslavia too in April of 1941, to no notable success. Interestingly, however, the Yugoslav Air Force operated 40 export models of the 'Sparviero' at the time of the invasion, making it one of the few moments in history where opposing sides used the same equipment!

No SM.79s were deployed against Britain during the Battle of Britain, nor in the Soviet Union during Operation Barbarossa.

Malta, 1940-1942

By the middle of the war, it had seemed that the Axis had near-complete control of the Mediterranean Sea (even if the Germans controlled most of it). However, there was one island in the middle of the sea that was still held by the British, from which they could harass Italian and German convoys headed for North Africa, called Malta.

In order to capture this strongpoint, vast air raids coordinated by the Luftwaffe in conjunction with the Regia Aeronautica were carried out from June 1940, featuring every aircraft type the two air forces could throw at it, including the 'Sparviero.' The first SM.79 units to be used in this air assault were the 30° Stormo, based in Sciacca, Sicily, and the 279° Squadriglia; however, numbers were soon bolstered by the arrival of the 10° Stormo. Throughout this two-and-a-half-year siege, multiple SM.79 units from throughout the Mediterranean would take part in the assault, and it is thus difficult to arrive at a full list of all the 'Sparvieri' units that participated.

During this battle, these aircraft fulfilled two main roles: strategic bombing of strongpoints and cities and convoy attacks. The opening of the campaign was heralded by a sortie of SM.79s on the 11th of June, 1940, when 55 were sent to damage Malta’s three airfields, escorted by a formation of MC.200s. The mission overall was a success, with the bombers being able to release their payload and all of them returning home, despite an interception by three (of the island’s six!) Gloster Gladiators.

Overall, this campaign developed in much the same way as the North African one had: the 'Sparvieri' were at first met with very limited air defence capabilities, allowing them to carry out raids at will. However, when the first Spitfire Vs flew into Malta in early 1942 to relieve the out-of-date Gladiators and Hurricanes based there, the SM.79's fortunes rapidly switched, requiring more substantial fighter cover to be provided for missions.

This can actually be recreated in a Single Mission in-game, “Operation Bowery”, where the player plays as a Spitfire taking off from a carrier, landing in Malta, and then going on to intercept some oncoming enemy bombers.

Torpedo modification and use, 1940-45

During the SM.79's tests for military service in late 1938, it was experimentally modified to hold a 450 mm torpedo. This wasn’t an ideal configuration, as the frame could become unstable when flying at low speed; however, at this time, the Regia Aeronautica didn’t have a large amount of varying bomber designs on which it could test this torpedo, and so it was decided that the 'Sparviero' would have to be used, with or without instability. Thus, by July 1940, the Speciale Unità Aerosiluranti ('Special Torpedo-Bombers Unit', later named the 278ª Squadriglia) was formed in order to test this aircraft’s anti-shipping capacity; a 'trial by fire', if you will. This unit was at first transferred to an airfield near Tobruk, Libya, in order to carry out anti-shipping operations against the Royal Navy, which at the time was severely hampering the Regio Esercito's abilities to operate in that theatre. Most of the crews for the Aerosiluranti ('torpedo-bombers'), however, lacked not only the necessary training, but also the equipment with which to carry out these precise operations, as early 'Sparviero' variants did not feature any torpedo aiming device, requiring estimation and a certain amount of luck to hit targets.

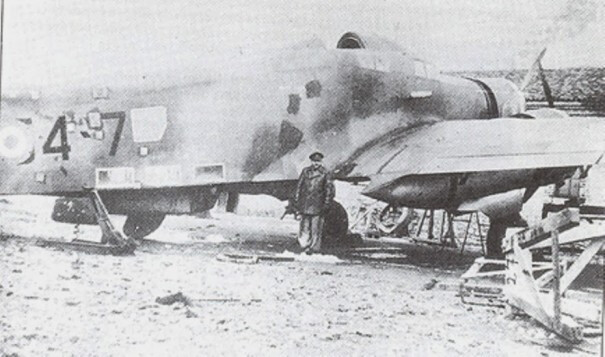

It was under these circumstances that the Aerosiluranti carried out their first operation of many, in a surprise evening attack on shipping in Alexandria harbor on 15th August. This mission was a total failure, however, as the anti-aircraft fire was so thick that the mission was aborted and only two of the five aircraft that set out returned, one without a wheel. The others had to force-land in the desert without dropping their loads on target.

The rest of 1940 would prove busy (if relatively unsuccessful) for the 'Sparvieri' of the 278ª Squadriglia, with the only notable success taking place on the 3rd of December, when 'Sparviero' ace Tenente Carlo Emanuele Buscaglia severely damaged HMS 'Glasgow' near Crete. This unit would go on to be one of the best SM.79 Squadriglia of the war, scoring hits on multiple Royal Navy vessels and severely damaging three of the Royal Navy’s best cruisers in the Mediterranean (including the 'Glasgow').

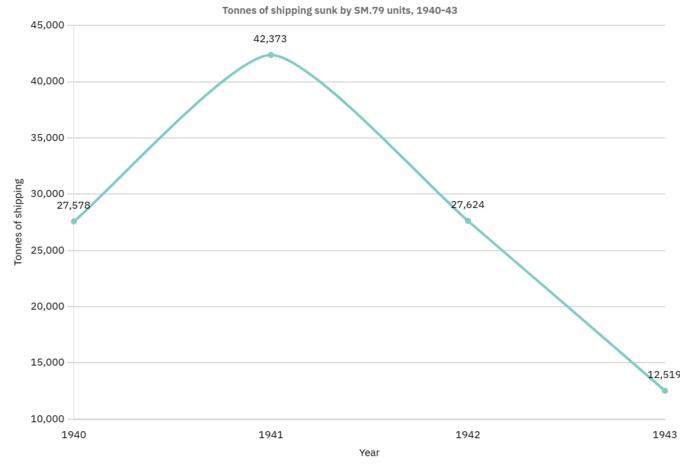

Despite the disappointment experienced by the Regia Aeronautica at the SM.79's debut as a torpedo bomber, by early 1941, many units had been converted into the Aerosiluranti role. In this year, the SM.79s met with great success, damaging many Royal Navy cruisers, destroyers, and battleships, and sinking dozens of supply vessels. In addition, the Aerosiluranti were central to the Siege of Malta: while their bomber counterparts bombed Maltese airfields and cities, the torpedo variants continually harassed the British convoys attempting to relieve the blockade, with mixed success.

Then, the following year during the invasion of Sicily, seven Aerosiluranti Gruppi were ranged against the Allied fleet, where consistent attacks (57 missions in five days) were made on the supporting aircraft carriers and cruisers in conjunction with the more numerous German Ju-88s and other torpedo aircraft.

However, by this time in the war, much like on land, the SM.79 was beginning to fall prey to the fighters of British and American aircraft carriers that were increasingly present in the Mediterranean. Planes such as the Seafire and Martlet could take off from a carrier, find and destroy a 'Sparviero', land, refuel, and take off again. This would prove a real problem for the crews of SM.79s, and, despite future modifications to try and modernize the bomber, it never enjoyed the unmatched superiority of 1938 again.

Post-Armistice service, 1943-1945

The A.N.R. (L’Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana, in English, 'National Republican Air Force, ' which was the air arm of the puppet government under the Nazis, the Italian Social Republic) on most of the SM.79s of Fascist Italy, which had surrendered through an armistice in September 1943 to the Allies. These continued to serve as torpedo bombers and transports, notably bombing the Anglo-American invasion fleet during the Anzio landings in January 1944. A few (15) were produced for this air force; however, the majority of them were former Regia Aeronautica veterans, mainly the bis/T.M. variant, which was only produced towards the end of Fascist Italy’s rule, in mid-1943.

Another notable mission carried out by the National Republican 'Sparvieri' was in June 1944, when a force of 12 modified SM.79s took off from the south of France at night and flew to Gibraltar in a surprise attack. Ten aircraft reached the unprepared British defenders, and three had to force-land in Spain due to running out of fuel, but overall the mission was a success, with the crews claiming 27,216 tonnes of shipping sunk. Similar missions would often be carried out by SM.79 units of the A.N.R., such as the attack on Bari harbor the day after the Gibraltar raid, to varying success. These units also partook in torpedo attacks on Allied shipping in the eastern Mediterranean in July, from bases in Greece. Overall, however, these aircraft suffered immensely at the hands of the Allies, whose fighter aircraft and intense anti-aircraft defenses from ships hampered their efficiency. The last 'kill' of this aircraft during the war would take place in January of 1945, just four months before the end of the war in Europe, when a 5,000-ton ship was sunk by torpedo.

On the Allied side, the co-belligerent Italian Air Force had been formed, consisting mainly of captured Regia Aeronautica machines, and among these were 29 'Sparvieri.' After the 1943 armistice, aircraft of the 41°, 132°, 131°, and 104° Gruppi were flown to the rapidly advancing Allied line in surrender. These aircraft, after an examination, were put into action once again under Allied colors. Under this air force, the 'Sparvieri' served numerous roles, mainly as transport for supplies and personnel, spreading propaganda leaflets in German-held northern Italy, and dropping spies of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) into enemy territory.

Post-war use

After the destruction of the Italian puppet government in 1945, the Aeronautica Militare (the new Italian Republic’s air force) was desperately trying to modernize its equipment, as native military technical innovation had effectively ceased after Fascist Italy’s surrender. The majority of these new designs were provided by the U.S.A. (like the P-47D-30), while Italy’s economy was getting back on its feet. Most designs that had been used by the Regia Aeronautica during WW2 were scrapped in Italy; however, the 'Sparviero' was one of the few of these aircraft that were retained. Due to their unusual speed for their design, these aircraft were used for transport, training, and target practice until finally ending service with their native country in 1952.

One aircraft (captured in Sicily) was retained by the U.S.A.A.F. for comprehensive evaluation, being assigned to the 79th Fighter Group. In tests the aircraft performed well; however, it was eventually scrapped.

Nations that operated the SM.79

The success displayed by the SM.79 in Spain and early in the Second World War aroused interest in other nations, who hoped to purchase this design. Air forces from all over the globe operated these machines, with some serving even into the '60s:

1. Lebanon: Four 'Sparvieri' were purchased by the Lebanese Government in late 1949, and entered service with the Lebanese Air Force that same year. These aircraft were similar to the Italian variants used during WW2, however no torpedo capabilities or waist-mounted machine guns were included. It was out of date by the time it entered service, and this especially became apparent when one 'Sparviero' was intercepted by Israeli Mystere IVA jet fighters, who forced it down into Israel. These aircraft were retired in 1965, and Lebanon was the last country to operate this aircraft for military use. The last two surviving SM.79s are both former-Lebanese machines.

2. Iraq: Four 'B' variants were bought in 1938, and these were used against British forces in the Anglo-Iraqi war of 1941. Following the Iraqi Government’s collapse, however, all four were destroyed.

3. Croatia: A few 'Sparvieri' were transferred into the Croatian Air Force from Yugoslavia after its defeat, where they were used during the Second World War in transport and anti-partisan roles.

4. Greece: One SM.79 was used by the RHAF (Royal Hellenic Air Force) after a counter-attack into Italian-held Albania in 1940 found a damaged 'Sparviero', which was then used as a transport aircraft until the German occupation.

5. Brazil: In 1938, three SM.79 Ts (standing for 'Transatlantico', or 'Transatlantic', which were racing variants equipped with extra fuel) flew from Rome to Rio de Janeiro. With a break at Dakar, the two remaining aircraft (one was left behind in Dakar due to engine failure) flew the entire journey in almost exactly 24 hours. This would prove a fantastic piece of propaganda for Savoia-Marchetti’s design (especially as Bruno Mussolini, the Italian dictator’s son, was piloting one of the SM.79 Ts with his name emblazoned along the fuselage as identification markings!), and upon arrival in Brazil, these aircraft were gifted to the Brazilian Air Force. These would later be converted for military use; in addition, three B variants were also ordered by Brazil. They were used until October 1944, by which time they had all been sold for scrap.

6. Nazi Germany: After the 1943 armistice, as well as including many SM.79s into the newly-formed A.N.R., the Luftwaffe also seized a few examples for their own use. Painted with a bright yellow underside (as was the Luftwaffe's convention for foreign aircraft, such as with the Vickers Wellington), these aircraft served as transports alongside the Ju-52 until the end of the war. Some had also been captured from Yugoslavia.

7. Fascist Spain: As previously mentioned, the Fascist government retained some SM.79 veterans of the civil war for use in their own army, as well as buying a few more. With a lack of Italian spare parts after the war, these were eventually officially retired in 1947, however they had been made redundant a few years before.

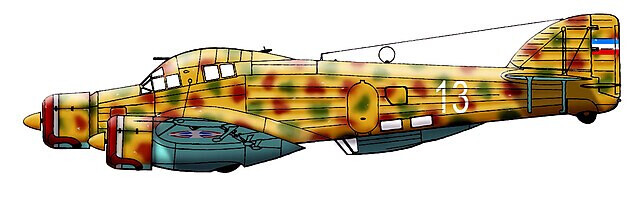

8. Yugoslavia: Forty-five serie 1 variants were ordered in 1939 (named the 'K' variant, specifically designated for Yugoslavian use) and had entered service with the Royal Yugoslav Air Force that same year. The level of cooperation between the two nations was notable. However, Italy was stopped from sending more deliveries to Yugoslavia due to pressure from Nazi Germany. Most of these machines escaped during the Axis invasion to Romania, the USSR (where three were operated by the Soviet Air Force) and Egypt, where 117th Squadron RAF employed them in the Middle East for a while.

9. Romania: The Romanian Air Force bought 32 of the aircraft (renaming it the IAR 79), in 1937 and 1938. Whilst some serie 1 variants were used, the 'B' variant was the most numerous and popular 'Sparviero' to see service with Romania, and this variant is thus depicted in-game under Romanian markings.

SM.79 Variants In-Game

1. Serie 1: The first variant of the SM.79, featuring a ventral gondola and 3x Alfa Romeo 126 RC 34 engines. Used in the Spanish Civil War and early WW2 campaign. Used for bombing and ground-attack.

2. Serie 4: Later variant, used in the majority of Italy’s theatres of war during WW2. Very similar design to the serie 1.

3. Serie 8: A further refinement of the serie 1, with the addition of an improved dorsal turret with a wider firing arc.

4. AS: Standing for Africa Settentrionale, this variant was designed for use in the hot, harsh climate of North Africa. Featuring a sand filter on the engines' carburettors and an extended radiator, there were not many radical changes from the serie 8.

5. bis/T.M: Being the first variant to be used for low-level torpedo bombing, quite a few changes were made to this variant, mainly being: the removal of the ventral gondola (more space being made for the torpedo), armour plating added to all crew-member positions and the replacement of the 7.7 mm Lewis guns with 12.7 mm weapons. Slower than previous versions.

6. B: Whilst Savoia-Marchetti were developing the three-engined SM.79 serie 1 in 1935, they developed in parallel to this project a two-engined version, which was a more common engine arrangement for bombers at the time. Naming it the SM.79 B, this prototype was rejected by the Air Ministry for military use (as it was deemed 'less safe' than a three-engined design). However Savoia-Marchetti retained its blueprints, perhaps with the aim of future export and conversion into a passenger plane. Reverting to a traditional glazed canopy meant that the pilot could be placed further forward in the cockpit, and the gondola could be dispensed with.

7. bis/N: This was a further refinement of the bis/T.M variant, with superior radio equipment being added (a problem which had plagued many aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica at the time). If using a torpedo, the bomb-bay, which would be empty, could also contain an extra self-sealing fuel tank, for long-range operations. Newer engines, the Alfa Romeo 128 RC.18, were added as well, improving its climb rate.

Surviving aircraft

Only two 'Sparvieri' survive in museums today, however wrecks have been found both submerged in the Mediterranean and on land. At least one is in a private collection.

One aircraft is kept in the Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics in Trento, Italy. This was one of the few aircraft sent to Lebanon after serving the Regia Aeronautica during the war, and was given the serial number L-113. This was donated to Italy in 1966. It has undergone restoration, and is now in Lebanese colours.

The other is kept in the Italian Air Force Museum in Bracciano. Coded L-112, this aircraft too served with the Lebanese Air Force, and was returned to Italy in the mid-'60s. Restored to its original Regia Aeronautica colours, this aircraft carries the markings of Tenente Buscaglia’s aircraft, consisting of Verde Mimetico squiggles over a Giallo Mimetico base.

- Combat Units of The Regia Aeronautica — Italian Air Force, 1943-45, by Chris Dunning

- https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Savoia-Marchetti_SM.79_Sparviero

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Savoia-Marchetti_SM.79_Sparviero

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZXScEN1OeeI&t=1s

- Profile Publications, Issue 89: The Savoia Marchetti S.M.79, by Giorgio Apostolo

- https://www.key.aero/article/fighting-sparrowhawk

- Purnell’s History of the World Wars Special: Bombers, 1939-1945