If someone mentions bomber aircraft, chances are a lot of people — particularly Britons — will immediately think of the Lancaster. It was so ubiquitous and performed so many unique and famous actions, that it will always be remembered as one of the most successful bomber designs of the Second World War.

Design

The Lancaster’s tale starts with Air Ministry Specification B.13/36 which called for a medium bomber powered by two massive engines to replace the Wellingtons and Hampdens in service at the time. Avro’s design was the Avro Type 679 Manchester which used two 24-cylinder Rolls-Royce Vulture engines.

Before the Manchester had first flown however, some at Avro, including head designer Roy Chadwick, were uneasy about the design. Thus Avro Type 683 was created, which used the Manchester’s fuselage and parts of the wing, but with four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. A Manchester with serial number BT308 was removed from the production line and modified into the prototype Type 683 at the end of 1940. Initially known as the Manchester Mk III it first flew in January 1941. The design was modified over several months and resulted in a largely new design, which now bore the name Lancaster.

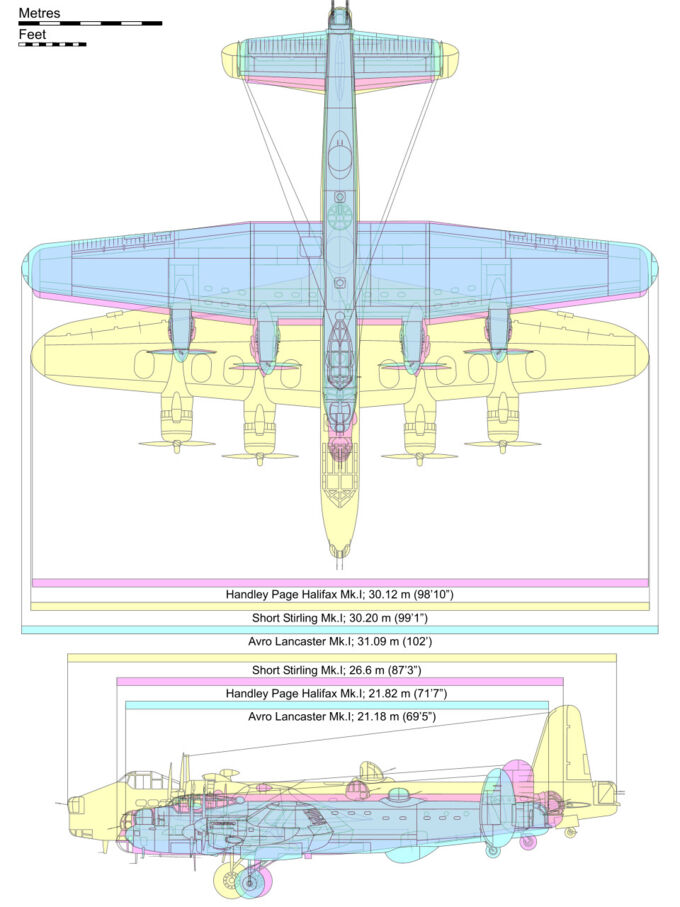

The Avro Type 683 Lancaster had an oval monocoque fuselage dominated by the enormous 10m long bomb bay. The cockpit was directly over the forward end of the bomb bay with navigation and radio stations just behind, under the large canopy. In the extreme nose, a glass dome was provided for the bomb-aimer. Three power-operated gun turrets in the nose, tail and dorsal positions provided the Lancaster with defensive capabilities. Some versions also carried a small ventral turret with two machine guns. Huge fuel tanks in the wings allowed the Lancaster to travel for 4,000km. Interestingly, it was essentially the smallest of the four-engined “heavies” used by the RAF, despite also carrying a heavier payload.

Armament

Offence

The Lancaster’s primary role was to carry tonnes of bombs long distances and to drop them on enemy targets. It carried out this role exceptionally, thanks to its massive and unobstructed bomb bay. This allowed it to carry a huge range of different ordnance without modification. Each different bomb load had a codename and was used for a different target. “Usual” for example was used for area bombing and consisted of 2,832 4-lb incendiaries and a 4,000lb “Cookie” blockbuster bomb. “Abnormal” comprised nine 1,000lb bombs and was used to destroy industrial targets. “No-ball” was intended to knock out V-1 flying bomb launch stations.

Defence

Defensively the Lancaster was seemingly well-equipped. Two Browning .303 machine guns were in each of the nose and dorsal power-operated turrets and four were in the tail turret. The tail guns each had 2,500 rounds and the others had 1,000 rounds per gun. Early B.Is and B.IIs carried a small ventral turret which was found to be very hard to use as it was sighted using a periscope which had a very narrow field of view, not suitable for air-to-air gunnery. Later versions didn’t carry this turret, the space instead being used for H2S.

The tail and dorsal turrets were always was a matter for much debate and experimentation. Initially Lancasters carried a Frazer-Nash FN-20 in the tail, which was often replaced by the marginally better FN-120. By the end of the war — after having tried the unreliable Rose turret, the FN-121, and various radar gun-laying systems — the RAF standardised on the radar-equipped FN-82 with two .50 calibre machine-guns which equips the Lancaster B.III in-game.

As for the dorsal turret, very early aircraft carried the Manchester’s “dustbin” turret, shared with the Stirling and Sunderland. Most eventually used the Frazer-Nash FN-50 or improved FN-150, with the distinctive bulbous dome and large fairing — designed to prevent the gunner from shooting the tail or the cockpit canopy by guiding a cam linked to the guns — being found on every mark of Lancaster. B.VIIs and late B.Xs used the heavier Martin 250 CE 23A turret used on the B-24 Liberator and equipped with two .50 calibre machine-guns. Other Lancasters trialled the FN-79 and Boulton-Paul Type H.

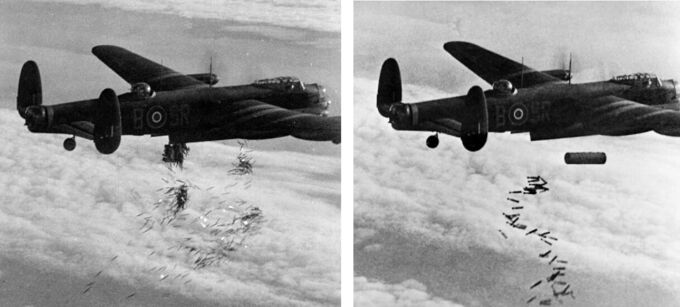

In addition to weaponry, Lancasters would also frequently deploy countermeasures such as the ubiquitous strips of paper-backed tin foil known as “Window” which blocked enemy radar. This early form of chaff was released in clouds via a chute in the nose by the bomb-aimer. This would hamper the enemy’s ability to estimate the size and direction of an approaching formation and confused night fighters and radar-guided flak guns and searchlights. On its first deployment in Operation Gomarrah in 1942, only 12 of 791 bombers were lost on the first night of sorties, a much lower casualty rate than normal. Crews reported flak guns firing randomly or not at all and searchlights wandering aimlessly without proper radar guidance. Although the enemy eventually developed tactics to mitigate the impact of Window it still helped reduce casualties.

Fatal Flaws

Although largely successful and capable, the Lancaster had its fair share of issues, some of which were shared with contemporary RAF designs, and some which were unique to the type. Many of these issues are often overlooked due to the lionisation of the aircraft and the focus on its finest moments.

Firstly the escape hatches were about 5cm (2 inches if you’re weird) smaller than those on the Halifax and Stirling, which were already a tight squeeze. This meant it was difficult for the crew to escape, especially when wearing a parachute and bulky flying gear and the plane was critically hit. The result of this was that only around 15% of Lancaster crews successfully escaped their stricken aircraft compared to 25% of Halifax and Stirling crews and 50% of USAF crews in B-17s and Liberators.

Scientist and mathematician Freeman Dyson calculated early in the Lancaster’s career that if they removed the turrets, gunners, and ammunition, the Lancaster would have been able to fly several thousand feet higher, and up to 50mph faster as well as reducing the number of men lost with each bomber. This could have saved the lives of thousands of crew attacked by night fighters as the increase in speed would have been just sufficient to allow the bombers to outrun them at full tilt. This doctrine of speed over defensive guns had already been proven in the hugely successful Mosquito. Unfortunately the Air Ministry rejected his proposal, suggesting that the morale benefit to crews of being able to fire back was worth the cost. In any case, new night fighter designs such as the He 219 soon entered service, negating the proposed speed gain.

Unfortunately the turrets that the Lancaster was equipped with were wholly inadequate for the task of defending the bomber. Almost all of the turrets that the Lancaster carried only had .303 machine guns, which were useless at the ranges that enemy night-fighters engaged from. Some Lancs which had up-gunned turrets were more likely to score hits, but there were very few such aircraft available. Interestingly, Lancasters equipped with the unreliable but more heavily armed Rose turret were found to have suffered lower losses than Lancasters with the usual FN-20s. This was attributed not the the better firepower — 60% of gunners reported stoppages in action — but simply due to the improved visibility allowing evasive action to be taken earlier.

Versions

- B.I — the original, fitted with Merlin XX engines.

- B.I Special — modified extensively to carry Grand Slam Bombs

- B.II — fitted with Bristol Hercules Engines due to fear of a shortage of Merlins. Also had bulged bomb bay doors, preventing use of H2S, so these more often kept their ventral guns, especially when the threat of Schräge Musik became apparent. 10mph slower and with a much lower service ceiling, only 301 were built.

- B.III — fitted with Packard-built Merlins, essentially the same as B.I

- B.III Special — specially modified for Operation Chastise.

- B.IV — Became the Lincoln B.I

- B.V — Became the Lincoln B.II

- B.VI — 9 made, used more powerful supercharged Merlin 85/87. Often used as Master Bombers due to improved performance.

- B.VII — final production version carried Martin dorsal turret and FN-82 tail turret

- B.X — built using American and Canadian materials. Mounted a Martin dorsal turret.

Service History

Trials began at Boscombe Down in June 1941 and B.I Lancasters were delivered to operational units from the beginning of 1942. The first mission flown by the Lancaster was mine-laying over Heligoland Bight on 3 March 1942 by No. 44 Squadron.

The Lancaster was found to be a deceptively pleasant plane to fly. It could out-turn some enemy night-fighters and could reach surprisingly high speeds in a dive. The Merlin (or Hercules) engines were reliable and powerful and some bombers were able to limp back home after one or two engines were knocked out in combat.

The type’s front-line presence quickly ramped up. The first losses were over Lorient on the 24 March and by 30/31 May, there were more Lancasters in service than Manchesters. On that night Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, Arthur “Bomber” Harris launched the first of his Thousand-Bomber Raids against Cologne, pooling every bomber he could from Coastal Command and the Operational Training Units.

The Lancaster’s war from there on in was much the same, flying out almost every night to lay waste to German cities, factories and infrastructure. Night missions were most common, almost no daylight raids were made in 1943-44, as the USAF’s bomber wings took the centre stage there. From late 1944-45 Bomber Command’s bombers again began flying daylight missions, as Allied air superiority meant that the formations could be escorted. At its peak, Bomber Command had at least 59 Squadrons of Lancasters online.

Daylight missions ran the risk of bumping into the Luftwaffe’s latest and most powerful fighters however. On the 31st of March 1945, a formation of Lancasters and Halifaxes was attacked by several Messerschmitt Me 262 fighter jets. The under-armed Lancasters fared even worse than the USAF’s B-17s and 8 were lost along with 3 Halifaxes.

Some Lancasters were converted to special duties to assist the strategic bombing campaign, such as those of No. 101 Squadron. These carried the “Flying Cigar” system which consisted of an additional German-speaking crew member and a pair of aerials above and below the fuselage. This allowed the Lancaster to broadcast onto German radio channels, so the extra crew member could disrupt enemy operations by giving false orders. Unfortunately this worked so well that night fighters quickly learned how to detect the source of the false orders and destroyed the “Flying Cigars”. No. 101 Squadron suffered the worst casualty rates of any squadron in Bomber Command but the system did successfully reduce overall casualties.

Radar

Over the course of its service, many small modifications or additions were made. Perhaps most important was the addition of airborne radar in the H2S ground-scanning unit. During testing of Airborne Interception radar on Blenheims in 1940, the boffins noticed that different ground features had distinct signatures. Thus work started to create a system to aid the bombers' navigation which at the time was dependant on radio-based systems such as GEE and Oboe.

H2S was first used in January 1943 to some success. Unfortunately for the RAF, on its second mission a unit was captured intact from a downed bomber. Enemy scientists pieced together how it worked and were shocked at its accuracy compared to other systems. Soon the Naxos radar detector was created and fitted to night fighters to allow them to home in on the signals produced by H2S. Luckily this didn’t have much impact on casualties, as crews used it very sparingly, aware that it could attract enemy fighters.

In addition to H2S, other airborne radar units were tested on the Lancaster. Some Lancasters' tail turrets were fitted with Frazer-Nash FN-121 turrets with “Village Inn” gun-laying radar, which worked very well but was a magnet for night fighters who could easily detect its signal. Thus Village Inn-equipped Lancasters were trailed behind the main formations of bombers to keep night nighters away from the rest of the force. This reduced losses overall, though I’d imagine might not have been popular with the crews flying with Village Inn onboard.

Master Bombers and Pathfinders

Early in the war, it was recognised that aerial bombing was very inaccurate, especially at night. Crews would semi-regularly fail to even find the correct target even with radio-based navigational aids such as Oboe. Thus, from the RAF tried several new methods of ensuring that the maximum amount of ordnance would hit the target.

The first step towards more accurate night-time bombing was made in July 1942 with the formation of the Pathfinders under the command of Wing Commander Donald Bennett. Formed of highly experienced crews and flying fast Mosquito bombers, usually at low level, the unit marked targets using large flares, colour coded to allow the heavy bombers to align themselves to make the best run depending on the weather conditions. This on its own improved accuracy but it was found that the bombers slowly crept back from the markers, aiming at fires started by the bombs dropped before them, rather than on the centre of the target area. Thus, the Master Bomber role was created.

The Master Bomber was an experienced Pathfinder who flew in a heavy bomber — albeit one upgraded with more powerful navigational and radio systems. It was his job to circle above the target area for the duration of the raid and to assist in guiding the formations of heavy bombers — which sometimes flew in on different routes — to their targets. He could order the bombers to adjust their aim to account for misplaced markers. Finally, he would also instruct other Pathfinder units to place new markers when the old ones burnt out. The combination of the Master Bomber and the Pathfinders dramatically improved accuracy. By 1944, Master Bombers usually flew in either Mosquitos or Lancasters, sometimes in the rare B.VI variant.

No. 617 Squadron and Special Operations

The Lancaster is perhaps best remembered for the multitude of unique and arduous missions it undertook, often in the hands of the highly skilled crews of the infamous No. 617 Squadron RAF.

The famed No. 617 Squadron was formed on 21 March 1941 for a mission so secret that the crews weren’t told about their target until the night they flew. Of course this was the stunning Dambuster Raid which was immortalised by the post-war film.

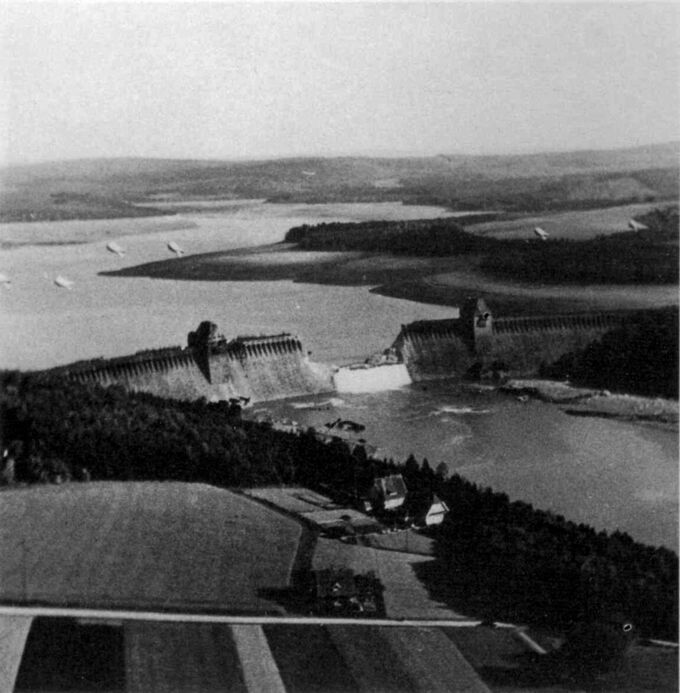

The idea for this operation had come from boffin Barnes Wallis, creator of the Wellington bomber among other achievements. Arthur Harris was convinced to allow some of his precious planes and crews to be diverted to this scheme and so plans were set out for Operation Chastise. Several Lancasters were heavily modified for the task. Their dorsal turrets were stripped out, as were the bomb-bay doors which were replaced by a mechanism which would spin the cylindrical “Upkeep” bomb to allow it to bounce across the water. Two searchlights were installed in the nose, aimed to converge when the bomber was 60 feet above the surface of the water over which they would fly to deliver the bomb.

Wing Commander Guy-Gibson was chosen by the Air Ministry to lead the unit and he in turn picked the crews, looking especially for pilots well-versed in low-altitude flying. For several months the crews drilled intensively in low-altitude flying, much to the displease of the locals who routinely had immense bombers roaring at tree-top level overhead.

The raid took place on the 16 of May 1943, with 19 Lancasters flying at or even below tree level for hours to reach the targets: the Möhne, Eder and Scorpe dams which supplied the factories of the Rhur Valley with power and water. The Möhne and Eder were successfully breached but the Scorpe was only damaged. 8 Lancasters were lost, some crashing into power cables such was the height at which they were flying. 53 men died and 3 were taken prisoner, a loss for which Wallis felt deeply responsible. The raid, although initially successful, in fact did not have the impact that was hoped. The dams were repaired quickly and most of the casualties caused by the flooding were prisoners and slave labourers. However this feat of daring and near-insanity was a much needed morale boost for the British as well as alarming to the Germans. Many residents of the areas near the dams later recalled the terror of hearing the Lancasters roaring past — not over — the church spires and trees in the villages.

After the raid No. 617 Squadron quickly adopted a new badge showing a broken dam and a new motto “Après moi le déluge” (French: after me the flood). The Squadron continued to engage in precision and low-level strikes for the rest of the war.

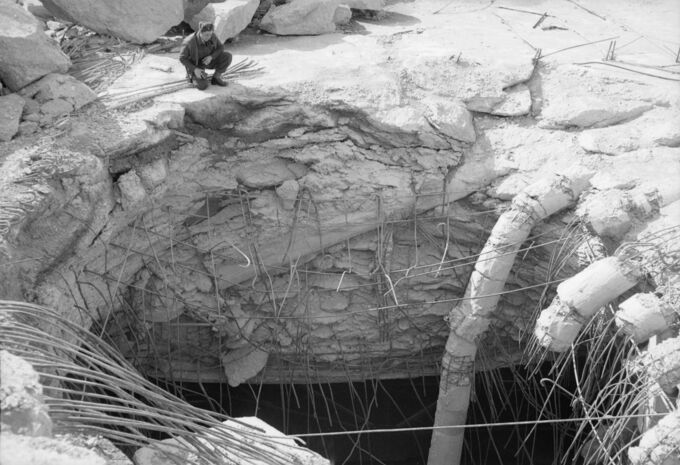

No. 617 Squadron was also responsible for the dropping of the colossal bunker-busting earthquake bombs the 11,000lb Tallboy and the 22,000lb Grand Slam (the largest conventional bomb used during WW2 and another of Barnes Wallis’ creations) which could only be carried by heavily modified B.I Specials. These had their gun turrets, armour, parts of the bomb bay and some crew removed to save weight. This weight saving meant that B.I Specials were much faster that standard Lancasters, earning them the name “Clapper Kites”.

Of particular note is the attack on Tirpitz. By 1944 the RAF and Royal Navy had tried almost everything to sink the dreaded sister ship of Bismarck. From torpedo bombers, to miniature submarines and conventional bombs, nothing had worked and the Tirpitz had retreated to the fjords of Norway. So on the 15 Spetember 1944, Lancasters from Nos. 617 and IX (another highly skilled bomber unit) Squadrons flying from near Archangel in Russia managed to drop a Tallboy bomb in the forecastle, damaging her and causing her to retreat to Tromsø further north. This was just within range of Lancasters flying from RAF Lossiemouth in Scotland and so, in October an attempt was made but abandoned due to cloud cover. Finally on 12 November 1944, bombers dropped several Tallboy bombs on and around the battleship, causing a magazine explosion under "Caesar" turret leading to her capsizing. The bomb to which the sinking is attributed was dropped by a Lancaster of No. IX Squadron piloted by Flight Lieutenant John Leavitt.

The Squadron’s precision flying was again put to use to cover the D-Day landings. Lancasters flew in precise patterns for hours off the Cap d’Antifer the night before, dropping Window — strips of tin foil which reflected radar — to create the impression on radar of a fleet advancing towards the French coast.

Beyond Combat

Some Lancasters were used as symbols of the war effort and were used to try and drum up support for the military and encourage the purchase of war bonds. One famous impromptu stunt performed by a Lancaster in this fundraising role was on 22nd of October 1943. A RAAF Lancaster named Q for Queenie and piloted by Flt/Lt Peter Isaacson buzzed the RAAF HQ in Sydney before flying under the Sydney Harbour Bridge in full violation of a 1931 prohibition. This wasn’t the last time such a stunt took place but the Lancaster was by far the largest aircraft to perform it.

In addition to combat, the Lancaster was heavily involved in Operation Manna in April-May 1945. The Dutch people were suffering heavily from food shortages under German occupation so the RAF launched a series of sorties to drop supplies from bombers into territory still held by German forces. The first sortie was flown on the 29th of April, without an official ceasefire agreement, by a Lancaster (nicknamed Bad Penny from the saying “a bad penny always turns up”). The sorties typically involved flying very low — around 15m up — to drop large amounts of supplies without parachutes.

From the 3rd of April to 31st of May 1945, some Lancasters were assigned a very special new role. Operation Exodus was the name given to the repatriation of Prisoners of War to Britain. Lancasters were modified to allow 20-24 people to travel inside them. Along with other types, Lancasters flew captured personnel back to their homes and loved ones, for some it would have been their first time back on British soil in 6 years.

Post War

Post-war the Lancaster remained in RAF service for several years, though never again seeing the intensity of its wartime operations. Its offspring, the Avro Lincoln, replaced it in the strategic bomber role so Lancasters were often used for maritime patrol duties or as photographic reconnaissance aircraft. their long range proving invaluable. In a continuation of one of its wartime roles, some Lancasters were modified to carry air-droppable lifeboats in the air-sea rescue role with the RCAF and RAF. A streamlined transport variant known as the Lancastrian was heavily involved in the Berlin Airlift in 1948-49 but was quickly replaced by more capable purpose-built designs. The final RAF Lancaster was a photo-recce aircraft that last flew in military service in 1954 marking the end of a long and storied career. It was replaced by the powerful V-Bombers (the Vickers Valiant, Handley Page Victor and Avro Vulcan) in the combat role and by its grandchild the Avro Shackleton in patrol duties.

A flight of RAF Lancasters toured the USA for a goodwill tour in summer 1946 visiting several airfields across the country. The aircraft were originally intended to be part of Tiger Force — a unit created to be sent to the Far East at the end of WW2 but which was never deployed as the war ended.

As the jet age dawned the Lancaster found a new use as a test bed for the new engines being created. These test beds variously had new engines installed in place of the outboard Merlins, in the nose, in the tail and in the bomb bay and proved very useful in propelling Britain into a new age of air superiority. Everything from Rolls-Royce Mamba turboprops to Nene turbojets and Swedish Dovrens were tested on Lancasters

De-militarised and modified Lancasters saw some use in mapping out Canada from the air. Their heavy payload allowed them to carry extra fuel and three large cameras for the job of photographing the huge expanses on the Canadian wilderness.

In addition to the British Commonwealth other users of the Lancaster included the French Armeé d’Air which sought to quickly rebuild itself after the war. They used the Lancaster in much the same way as the RAF did, primarily for maritime reconnaissance and patrol duties before home-grown jet bombers and aircraft came into service. The aircraft they used were ex-RAF B.Is and B.VIIs which were modified to the French requirements, losing some turrets but gaining new radar systems, sonarbouy and flare chutes and dual controls.

The Crew

The Lancaster typically carried 7 or 8 crewmen, dependent on the mission. Daylight missions typically required the full 8 crewmen, as it was deemed necessary to have the front gun turret manned at all times in case of frontal attack. This occasionally lead to the bomb-aimer, who lay directly below the gunner, getting his head stamped on in moments of excitement. During night missions the bomb-aimer also operated the front guns, when not responsible for releasing the bomber’s deadly payload cutting the crew to 7. Certain versions such as the Dambusters' B.III Specials or the B.I Specials removed turrets, reducing the crew to 5 or 6 men.

Many crews were positive about their Lancasters. Pilots appreciated the power and manoeuvrability over other types and over enemy fighters. Similarly crews felt much more comfortable with the reliable Merlin engines than the Manchester’s Vultures.

Flying in one of these beasts was not a walk in the park however. As with all large aircraft at the time, flying it took a great deal of physical strength due to the linkages between controls and control surfaces. Missions frequently lasted for six hours or more, so extreme endurance was required of the pilots. In addition, temperatures could and would plummet at high altitudes making life inside a Lanc very unpleasant. Although there was a heating vent that took hot air from the engines into the cabin, it was largely only beneficial to the navigator and radio operator cocooned in the fuselage. The rest of the crew had to deal with the constant 180mph+ draughts and biting cold, only somewhat alleviated by unreliable electrically heated flying suits.

The tail gunner had the worst lot of all however. He was stuck in a cramped, draughty turret, separated from the rest of the crew by armoured doors which served as his backrest. Temperatures in the tail turret could reach -50C and it wasn’t uncommon for “Tail-End-Charlie” to become hypothermic or frostbitten. Many gunners also knocked out the central section of perspex to allow themselves to see better — this was known as the “Gransden Lodge” modification — but this further reduced temperatures. In addition to these woes, escape in an emergency was very difficult. His parachute was stored in the fuselage, so he would have had to turn the turret, open the doors, squeeze out to grab his parachute then get back in, turn the turret to one side and roll out the back into space. Needless to say this was incredibly difficult in the best of times and tail gunners suffered very high mortality rates.

There are many tales of bravery surrounding the crews of Lancasters and of Bomber Command in general. 7 Victoria Crosses were awarded to pilots of Lancasters — including Guy Gibson for Operation Chastise — and one to a gunner, one to a flight engineer and one to a radio operator. Half of the 10 awarded to Lancaster crew were posthumous.

The flight engineer Norman Cyril Jackson received his for actions on the night of the 26-27 of April 1943. His Lancaster was attacked by a night fighter, causing the starboard wing to catch fire. Despite being wounded to crawled out onto the wing to try and put out the fire, getting badly burnt in the process. As he was doing so the fighter made another pass, shooting him in both legs and blowing him off the wing. His burnt parachute just about worked as he fell over 6,000m, landing hard and sustaining further injuries before being taken prisoner. His VC was awarded on 23 October 1945, alongside Leonard Cheshire’s, another veteran of Lancasters who received his for flying over 100 missions in Lancs, Mosquitos and Mustangs. Jackson later remembered that Cheshire, despite his higher rank, had insisted they go up together and had asked King George VI to award Jackson’s medal first, saying “This chap stuck his neck out more than I did — he should get his VC first!”, against protocol.

Final Thoughts

The Lancaster’s intense involvement in the war in Europe was reflected in the enormous tally of losses suffered. Of 7,377 built, 3,836 were lost over the course of 156,192 combat missions in 4 years. In addition, just over 55,000 men were killed in action or accidents while serving with Bomber Command during the Second World War. The majority of these lost were heavy bomber crews with an average age of only 22, of which a large portion were Lancaster crews, as it was the most numerous type to ever see service with the Command.

Despite the grim statistics, Adolf Galland — a German fighter ace with 104 aerial victories — considered the Lancaster to be the best night bomber of the war. Arthur “Bomber” Harris referred to it as Bomber Command’s “shining sword” and, at least for a time, Churchill was very supportive of the bravery of the crews flying over Germany night after night. Understandably, a lot of politicians and officers distanced themselves from the strategic bombing campaigns that defined most of the Lancaster’s service life when the scale of the devastation and suffering became apparent post-war. But this doesn’t detract from the bravery of the young men in their bombers, fighting against invisible night-fighters and terrifying flak, and today two Lancasters remain airworthy as tribute to them, one still flying with the RAF. In addition, the type has been immortalised in film, along with the Spitfire and Mosquito, in films such as The Dam Busters and the sight and sound of the enormous machines barrelling along at roof level will forever be remembered.

Sources

- Ross, Peter (?). Sky History, Lancaster: The forging of a very British legend

- Allwood, Greg (2020). The Avro Lancaster in all its glory: Stats and facts

- Anon (2016) 'Avro Lancaster', Aviation Archive, Issue 29, pp63-67

- Wood, Valerie Kaiyang (2022). The Avro Lancaster: Beyond the Second World War

- Bomber Command Museum of Canada (?). Me 262 Fighter Attack

- Classic Warbirds (?) Lancaster

- Classic Warbirds (?) 25 Avro Lancaster Facts

- Pathfinder Craig (?) Master Bomber

- My own wanderings around RAF Museums Hendon and Cosford