The Belgian Armed Forces—known as Defensie (NL), La Défense (FR), and Belgische Streitkräfte (DE)—serve as the national military of the Kingdom of Belgium. The monarch, the King or Queen of the Belgians, acts as the commander-in-chief. Belgium operates a professional military force, as conscription was officially suspended on February 5, 1995.

The Belgian Army was established following Belgium’s independence in October 1830. Initially, only the Land Component (Army) and Marine Component (Navy) were organized as separate branches. However, as of 2022, the Belgian Armed Forces have been restructured into four primary components, with a fifth currently under development:

- Marine Component

- Air Component

- Medical Component

- Land Component

- Cyber Component

This modern organization reflects Belgium’s commitment to adapting to evolving military needs and emerging domains such as cyber defense.

Table of Contents

In 1831, to defend the national coast and the Scheldt River, King Leopold I established the navy. It was also intended to support Belgium’s colonial ambitions. However, in 1862, due to a lack of interest and funding, the Royal Navy was dissolved.

On February 1, 1946, the birthplace of the Navy was established in Ostend, emerging from the Royal Navy (under Dutch rule), the Crew Depot (founded during World War I), the Naval Corps (founded in the 1930s), and eventually from the Belgian section of the Royal Navy (World War II). In August of that year, the Ministry of Defense made the General Mahieu Barracks in Ostend (later renamed Barracks Boatswain Jonsen) available to the “new” Navy.

In peacetime, the Navy remained under the authority of the Board of Navigation, but in wartime, it would be part of the Ministry of Defense. This peculiar duality remained in place until March 1, 1949, when the Navy was definitively incorporated into the Ministry of Defense.

From the outset, there were debates surrounding the birth of the Belgian Navy, with the following key dates consistently being points of discussion:

- April 3, 1941, with the “Admiralty Fleet Order,” which added a Belgian section to the British Royal Navy.

- February 1, 1946, when a decree from Prince Charles stated that the aforementioned section would become the “Navy.”

- March 1, 1949, when the “Navy” was definitively incorporated into the Ministry of Defense.

Over the course of 70 years, much changed. In 1951, the Zeebrugge Reserve Depot and the Maritime Command in Antwerp were established. In 1952, the Marine Training Center was completed. In 1958, the Nieuwpoort Reserve Depot and the Mine Clearance School in Ostend were founded. A Navy helicopter squadron (Flight Heli) was established in 1961. On September 27, 1976, the new Navy base in Zeebrugge was inaugurated. At that time, there were also naval bases in Kallo, Ostend, and Nieuwpoort, with a total of about 4,500 personnel.

What started as a small, young Navy with a few ships grew into a mature naval component with new ships and, above all, advanced high-tech equipment.

In 1990, the Navy was renamed the “Marine,” and it has since been largely centralized in Zeebrugge. What remains unchanged is its mission: to protect essential values and defend the vital interests of the country and its allies.

2. Early history 1830-1913

When Belgium split from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830-31, it was expected that Belgium could play the role of a neutral buffer state between the great powers of France, the United Kingdom, and Prussia. This would allow Belgium to avoid the need for an expensive standing army and instead rely primarily on a smaller, part-time militia, such as the existing 'Burgerwacht' (Civic Guard). However, it soon became clear that Belgium would need a regular army. The basis for recruitment was “selective conscription,” where exemptions could be purchased. In practice, this meant that only a quarter of young men actually served in the military, with the majority coming from the poorer segments of the population.

As part of its national neutrality policy, the Belgian army in the 19th century was deployed as an essentially defensive force, with fortifications along the Dutch, German, and French borders. Due to recruitment problems, the army remained below its intended strength of 20,000 troops. In 1868, stricter legislation on conscription was introduced. During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, a general mobilization was declared for nearly an entire year, leading to significant issues with training and structural weaknesses. However, an improvised military intelligence service, working with State Security, and the presence of Belgian units along the borders ensured that the fighting never spread into Belgian territory.

Until the late 1890s, the Belgian army relied on a selective conscription system, at a time when most European countries had introduced universal conscription based on the Prussian model. In Belgium, recruits were selected through a lottery system. However, those selected could avoid conscription by paying for a substitute. This system favored the wealthy and was seen abroad as inefficient and unpatriotic. For those selected, compulsory military service lasted eight years, followed by five years in the reserves.

In 1864, the Belgian Expeditionary Corps (known as the Belgian Legion) was formed for operations in Mexico. The purpose of this 1,500-man unit was to serve as the personal guard for Empress Charlotte of Belgium. It consisted mainly of volunteers from the Belgian army. In Mexico, the Belgian Legion was part of the imperial forces before returning to Belgium in March 1867, where it was disbanded.In 1885, the Force Publique (Public Force) was established to serve as a military garrison and police force in the Belgian Congo, which was directly controlled by King Leopold II. Initially, the unit was composed of various European mercenaries. When Congo became a Belgian colony in 1908, the colonial force was staffed with Belgian officers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, due to concerns over the repeated crises between Germany and France, the Belgian army underwent its first major reforms. In 1909, the lottery system was abolished, and a general staff was established. The general staff was heavily involved in managing the Second Moroccan Crisis over Agadir in 1911. In 1913, universal conscription was introduced in Belgium, which grew the army to 33,000 soldiers in peacetime. Through general mobilization, the army could be expanded to 120,500 men. The Royal Military Academy was founded in 1834, followed by the establishment of an École d’Application and an École de Guerre for the training of the military staff. One of the innovations pioneered by the Belgian army was the training of a corps of specialized officers who handled financial matters, personnel, and general administration. However, when the army expanded significantly in 1913, a shortage of trained staff officers quickly emerged.

3. World War I

3.1. The Belgian Army in 1914

On the eve of World War I, the Belgian Army consisted of 19 infantry regiments (line infantry, riflemen, and carabineers-grenadiers), 10 cavalry regiments (guides, lancers, and cavalry riflemen), and 8 artillery units (mounted, field, and fortress artillery). Supporting troops included engineers, gendarmerie, fortress troops, train guards, and civic guards. The seven divisions of the field army were intended to form a mobile fighting force, while the 65,000 fortress troops served as a garrison for the key forts around Antwerp, Liège, and Namur. These fortifications had been built in several phases, starting in 1859. However, by 1914, not all of the forts were completed. While these forts were well-designed by 19th-century standards, they were ultimately outmatched by the development of heavy howitzers.

3.2. During the war

When World War I broke out in August 1914, the Belgian army was in the midst of the aforementioned restructuring. As a result, and due to the swift occupation of Belgium, only twenty percent of the men were mobilized and incorporated into the military. Ultimately, 350,000 men were involved, although one-third of this number did not directly participate in the fighting.

Belgium was unexpectedly invaded by the Imperial German Army, which was about 600,000 strong. The small, poorly equipped Belgian army, consisting of 117,000 men, managed to hold off the German assault near Liège for ten days. The Belgian army fought between the forts and with their support. This strategy relied on the Napoleonic concept of an advance guard that would cut off part of the enemy’s forces from the main enemy corps. French authorities and the French public were thrilled by this Belgian resistance, which the Germans had not anticipated. The Belgians were able to effectively delay the Germans, allowing the French army to withstand the German attacks at the First Battle of the Marne.

After the Battle of the Silver Helmets, where the German cavalry and supporting infantry were defeated by several Belgian divisions, the Belgian army held the German troops at the Antwerp Position. After two months of fighting, the Belgian army retreated behind the Yser. The decisive Battle of the Yser was ultimately won with the help of the French and the British, relying on flooding by the Belgian engineers.

For four years, under the leadership of King Albert I, the Belgian army defended the left wing of the Allied front between Nieuwpoort and Ypres. The Belgians received help from the Triple Entente but did not participate in the major Allied offensives, which King Albert considered too costly (both financially and in terms of manpower). In 1916, a number of Belgian armored cars were moved from the Yser front to Russia to assist the Russian Empire.

In Africa, a Belgian colonial company helped in the occupation of the German colony of Togoland. The Congo-based Force Publique played a significant role in the East African Campaign against German forces in German East Africa, where more than 12,000 askaris fought under the command of Belgian officers during the Allied offensive in February 1916. The largest contribution in Africa was the capture of Tabora in September 1916 by troops led by General Charles Tombeur.

After four years of war in Belgium, the Belgian army, on May 26, 1918, numbered 166,000 men, of whom 141,974 were actively engaged in combat. The army consisted of twelve infantry divisions and one cavalry division. The army had 129 aircraft in its inventory. From September 1918 onwards, the Belgian army participated in the Allied offensive, which culminated in victory on November 11, 1918.

4. Belgium during the Interbellum

4.1. Early modernisation

After the armistice with Germany in 1918, the Belgian government aimed to continue the defensive strategies employed in 1914. While substantial investments were made in reinforcing the fortresses of Liège and Antwerp, which had proved ineffective during the First World War, comparatively little effort was devoted to acquiring tanks and aircraft for the military. Despite their shortcomings, the fortresses were bolstered with artillery and infantry, and tanks were integrated into infantry units to create a homogeneous, linear defensive front.

4.1.1. German units

Meanwhile, dedicated tank units were emerging in German armies during the 1930s, reflecting a shift in modern military doctrine. During the interwar period, the Belgian Army also utilized Haren Airport, originally built by the German occupiers during the First World War, as part of its limited air capabilities.

4.1.2. Further reductions

By 1923, the Belgian Army had been reduced to twelve divisions, and by 1926, it had been further reduced to just four divisions. The force primarily consisted of conscripts who served a brief thirteen-month term before transitioning to the reserves.

In 1932, the Minister of National Defense introduced the doctrine of integral territorial defense, a strategy focused on protecting the country from its borders. In March 1936, following a heated debate that culminated in the tumultuous departure of the Chief of the General Staff, this defense doctrine became more deeply rooted. It was particularly shaped by the sense of abandonment felt by the populations of Liège and Luxembourg, who feared they would once again endure the horrors of invasion in the event of a German attack.

4.1.3. Integral territorial defense

To execute this strategy, it was essential to have mobile troops capable of swiftly moving to the eastern border. This led to the creation of mobile units, such as the Ardennes Hunters. Established by a Royal Decree on March 10, 1933, these units spurred the development of specialized motorized artillery. It was during this period that Belgium’s first tank hunters and self-propelled guns were created, including the C.47 gun on a Vickers-Carden-Lloyd Mark.IV chassis and, a little later, the T.13 Type I, which will be known as the T.13 B1.

However, the defense policy led by Devèze, supported by a few members of the general staff, ultimately did not prevail in the long run. The complete defense of the country relied on two critical conditions: the maintenance of Franco-Belgian agreements and the non-militarization of the Rhineland, as outlined in the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Agreements.

Rather than focusing on an organized defense along the border itself, the strategy aimed to conduct delaying actions in the Ardennes, buying time to establish more robust defense lines along natural obstacles, such as the Albert Canal and the Meuse River, or pre-existing fortifications like the KW Line, which ran between Koningshooikt and Wavre. Despite this shift in strategy, the military continued to recognize the importance of mobile anti-tank capabilities. Even in the face of defeat, the army’s leadership understood the vulnerability of the Ardennes to armored assaults.

Captain Liddell Hart himself emphasized the critical need for mobile anti-tank capabilities to defend the Ardennes. As a result, the Chasseurs Ardennais and Cyclistes-Frontières units, tasked with conducting delay operations in the eastern part of the country, were given priority in the allocation of mobile anti-tank resources, specifically the T.13. These units greatly appreciated the T.13, finding it especially well-suited to their mission needs.

4.1.4. The T.13 series — the first series-produced tank destroyer in Belgian service

As a result of Devèze’s strategy, this vehicle proved essential within the framework of the doctrine of defense in depth, which necessitated the army’s ability to maintain mobility, along with its anti-tank units. Although the 47mm C 47 L/30 D gun was excellent, it struggled to keep up with mechanized units when towed and required significant time to deploy into battery. These limitations could be partially addressed by mounting the gun on an armored and motorized chassis, such as the T.13. Therefore, it was crucial to equip as many units of the Belgian army as possible with this vehicle.

This type of vehicle, while capable of destroying enemy armored vehicles, was a relatively inexpensive weapon system to produce. Furthermore, the Belgian army possessed the two key elements needed to rapidly develop such a weapon: a high-quality anti-tank gun manufactured domestically and a tracked chassis that could also be produced by Belgian forces.

Producing actual tanks would have been significantly more expensive (300,000 Belgian francs, compared to 160,000 for a tank destroyer) and would have taken longer. Additionally, these vehicles might have encountered technical issues due to the Belgian industry’s limited experience in tank production.

The license to manufacture the T.13 chassis was purchased from the British company Vickers-Carden-Loyd in 1933. This purchase proved highly advantageous for state finances, as producing 48 T.13s in Belgium would cost 5,935,680 Belgian francs, compared to 7,200,000 francs in Great Britain. At a time when minimizing expenses was crucial, the savings from producing the T.13 domestically were invaluable. Additionally, the national production of the tank provided employment for Belgian companies and their subcontractors.

The companies involved in the production of the T.13 included Miesse from Buizingen (responsible for the T.13 B1 and B2 chassis), the SA des Ateliers de Construction de la Meuse in Sclessin (which modified the T.13 artillery tractors into B2), Cockerill (which manufactured the 47mm gun parts), the Ateliers de Construction from Familleureux (which produced the chassis for the T.13 B3), and F.N. Herstal, which supplied the Browning machine guns. Additionally, a variety of smaller companies benefited from the production of the T.13 by supplying essential components such as optical instruments, metals, and other materials to the larger factories.

Introduced in 1934 as part of the integral territorial defense strategy, the T.13 tank destroyer/self-propelled gun also proved its value as an anti-tank weapon. The T.13 reflects the various defensive strategies employed during the 1930s and aligns with the efforts made in the interwar period to enhance the mobility and motorization of the army. However, despite the presence of vehicles like the T.13, the campaign of May 1940 exposed the heavy, immobile nature of Belgian troops, showing that they were not fully suited for in-depth defense. This issue continued to be addressed with further development and improvements throughout the late 1930s, with an emphasis on mobility.

Throughout the interwar period, political authorities in Belgium faced a security dilemma: how to safeguard the nation’s territory while avoiding the provocation of neighboring states by acquiring overly offensive weapons. The assault tank, with its strong offensive connotations, posed a particular challenge. Since Belgium’s war aims were focused on defense rather than aggression or incursions into enemy territory, it is understandable that successive governments were hesitant to invest in such an expensive and aggressive weapon. This reluctance was evident when the Combat Tank Corps, dissolved in 1935, was replaced by a corps focused on anti-tank escort weapons with a more defensive role.

Among the few Belgian machines that could be considered true assault tanks were the twelve Renault ACG 1s, which were equipped with a C.47 F.R.C. Mod.31 cannon and featured a fully enclosed armored combat compartment. These tanks, part of the cavalry, were the only ones that could be classified as full-fledged assault tanks. The army also had another tracked armored vehicle, the T.15. The T.15 was a license-produced Vickers Carden Loyd Light Tank Model 1935 with a custom-built belgian conical turret. While equipped with a 13.2 mm Belgian-produced Hotchkiss machine gun capable of engaging light tanks, the T.15 was weakly armored and lacked offensive power. Like the Renault ACG1, the T.15 was officially designated as an armored car, although in reality, it functioned more as a light reconnaissance tank. Until 1936, Belgium was allied with the Third French Republic and the United Kingdom. However, it declared neutrality again after that, despite Adolf Hitler having come to power in Germany three years earlier and the German remilitarization of the Rhineland on March 7, 1936, in violation of the Locarno Treaties.

Belgium only realized the strength of the new German army, the Wehrmacht, with the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. King Leopold III declared a general mobilization, and 650,000 Belgians were mobilized.

4.2. Defence industries in Belgium from 1814 to 1939

Only 160 years ago, Belgium was the first industrial nation on the continent and the second in the world. In 2017, CMI (Cockerill Maintenance & Ingénierie) celebrated its 200th anniversary in Seraing, near Liège. Belgium was the first continental country to follow the United Kingdom into the industrial revolution, thanks to the introduction of the steam engine at the end of the 18th century. Initially, the country industrialized its textile industry, with major centers in Ghent (for cotton) and Verviers (for wool). Under French administration from 1795 to 1814, coal was mined in the Borinage region (southwest of Mons, in the province of Hainaut) to supply Paris via the river network.

However, Belgian heavy industry truly began to flourish under Dutch rule from 1815 to 1830. King William I sought to ensure that the southern part of his realm would supply industrial products to the northern Netherlands. He supported industrial tycoons like John Cockerill, an Englishman who had come to Verviers with his father to build textile machinery. In 1817, the Dutch king sold him the former castle of the Prince-Bishops of Liège in Seraing, tasking him with developing steel manufacturing in the region. To honor his contributions, a statue of John Cockerill stands in the center of Place Luxembourg in Brussels' European quarter. In 1822, the King of the Netherlands also founded the Société Générale to promote national development. The bank later became known as Société Générale de Belgique in the early 20th century. In 1827, the continent’s first coke furnaces were put into service in Wallonia.

After some post-independence turmoil in 1830, when Belgium lost the Dutch market, the country experienced an extraordinary growth spurt from 1840 to 1872, outpacing all its neighbors and nearly matching the rapid industrial expansion of the United States. The average productivity per furnace was the highest in the world, and Charleroi became a global leader in glass production. By 1850, Belgium boasted the highest density of railways per square kilometer.

By 1892, 44 of the 50 largest companies in Belgium (excluding banks) were heavy industries, mostly based in Wallonia. However, a general economic decline began in the 1890s and would last until 1896. Seeking new opportunities abroad, many industrial groups reliant on the Société Générale de Belgique, such as Empain and Cockerill, turned to overseas ventures, including the construction of railways in Congo.

Meanwhile, the central region of Belgium, particularly the Brussels-Antwerp axis, began to gain momentum with the rise of new industries. In 1894, Gevaerts, a photography company, was founded in Antwerp. After the First World War, major automotive companies like Ford and General Motors established operations in Antwerp, while Renault set up in Brussels (Vilvoorde). A significant shift occurred in 1917 with the discovery of coal in Limburg (eastern Belgium), marking a new chapter in Belgium’s industrial development. This discovery paved the way for the growth of electricity generation, glass production, petrochemicals, non-ferrous metals, and artificial fibers, particularly in Flanders.

There were 3 major defence industry partners in Belgium:

- The industry Giant: CMI (Cockerill Maintenance & Ingénierie)

- The weapons manufacturer: Fabrique National in Herstal

- Fonderie Royale de Canons in Herstal

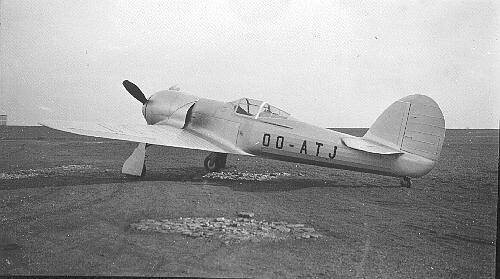

There were however many smaller defence industries, such as the Munitions company MECAR, the airplane-factories of Stampe-Vertongen, Sociéte Anonyme Avions et Moteurs Renard and SABCA, but also SA des Ateliers de Construction de la Meuse in Sclessin, the Ateliers de Construction from Familleureux, the Zeebrugge Aéronautical Construction Company and the royal foundries at Zeebrugge can be seen operating in this period.

Especially in the terms of aviation Belgium saw a large assortiment of domestic designs emerge during the 1930s under the Sociéte Anonyme Avions et Moteurs Renard company for fighter, training and reconnaisance aircraft.

The designs that followed were highly advanced for their time. These included the first passenger plane with a pressurized cabin, the R-35, and a fighter aircraft with capabilities on par with the Hawker Hurricane. Both planes initially garnered significant interest, but after a series of test flights ended in crashes, the Belgian Air Force and Sabena canceled their orders and reverted to British models. However, the R-36 was not the only modern fighter aircraft developed by Renard; there were also the R-37 with a radial engine and the R-38 featuring a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. Additionally, plans were in place to develop a fighter with a pressurized cabin, the R-40.

The most remarkable design, however, was the R-42, a twin-boom version of the R-40. This design was similar to the later Messerschmitt Bf 109Z and the Twin Mustang, but like the R-40, it was never fully completed in favour of purchasing Hurricanes. This preference for foreign products, which had to be acquired at a much higher cost through SABCA due to its contract, led to the stagnation of Belgium’s aviation industry untill after the Second World War.

5. World War II

In May 1940, the Belgian army had 22 divisions, mostly infantry, with a standing force of 100,000 men, 440,000 mobilized recruits from 1939, and a total of 900,000 including reserves—an impressive feat for a country with a population of 8 million. They also had about 200 AFVs distributed across divisions in small numbers, and nearly 700 towed anti-tank guns, served by artillery tractors, trucks, or Ford-based Marmon Herrington armored cars. However, only two divisions were fully mechanized, along with one armored regiment and two motorized divisions.

After the Mechelen incident, in which a German plane crash near the Meuse River revealed German plans, the Allies were informed of a German invasion strategy. The plan aimed for an invasion through Belgium, targeting western coast harbors, essentially repeating the 1914 Schlieffen Plan. However, both King Leopold and General Raoul Van Overstraeten, his aide-de-camp, suspected a German deception and believed a wide encirclement through the Ardennes forest was more likely. Despite their warnings, General Gamelin disregarded them and adhered to the Dyle Plan. According to this plan, the Belgian army was to hold the Antwerp-Liège-Namur line along the borders to delay the Germans, allowing French forces to position themselves before retreating to join with the French army, creating a narrower and more defensible front.

5.1. The Battle of Belgium

In May 1940, the Belgian defense suffered a devastating blow when German Fallschirmjäger quickly captured Eben-Emael, a key fortification, in one of WWII’s most audacious airborne operations. This not only disrupted Belgium’s deployment schedule but also derailed the Allied Dyle Plan. With well-coordinated attacks, the Germans seized crucial bridges over the Meuse and Albert Canal, neutralizing fortifications along the way, and launched their main offensive.

Supported by the Luftwaffe, Army Group B advanced rapidly through Belgium, crushing opposition as they followed the “Fall Gelb” strategy. During the border battles on May 10-11, Belgian lines along the Maastricht, Bois-le-Duc, Scheldt, and Albert canals were assaulted, and some were breached. However, the 1st Belgian Light Infantry and later the Belgian Ardennes Light Infantry held up the German 1st Panzer Division for up to eight hours at Bodange, and the west bank of the Albert Canal was held for 36 hours. After the withdrawal of the 4th and 7th Belgian Infantry Divisions, the French 7th Army failed to link up with the Dutch forces, clashed with the German 9th Panzer Division near Tilburg, and retreated to Antwerp.

From May 12-14, Belgian forces delayed the Germans further, holding Liège and Namur, executing demolitions and scoring kills with their T13 anti-tank vehicles. The 47mm C.47 F.R.C. Mod.31 gun proved effective against the Panzer III and IV, but the Belgian vehicles were vulnerable to most German tanks and anti-tank guns because of their lack of thick armour on most models. Despite these setbacks, Belgian forces managed to delay the German advance during the Battle of Tirlemont and Battle of Haelen.

The major armored clash occurred at the Battle of Hannut on May 12, where French elite armored forces clashed with German forces. Despite heavy losses, the Germans emerged victorious, as superior French tanks were undone by poor tactical deployment.

On May 15, the Allies learned that German Group A had broken through at Sedan, prompting plans for a massive withdrawal from Belgium. The Belgian army retreated from Liège and prepared to defend Antwerp. Antwerp and Namur resisted until May 22-23, but Brussels fell on May 18, and the Belgian government fled to Oostende. By May 20, the Belgian situation was desperate. Despite their best efforts, the remaining armored forces could not mount a successful counteroffensive as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) retreated. King Leopold, instead, focused on defending the Belgian west coast harbors.

On May 23, the French launched a counter-attack but gained little ground. By May 24, the Belgian front was reduced to a defensive line along the Yser River, linking with the BEF. On May 27, after fierce fighting in which Belgian forces inflicted tactical defeats on German divisions, the Leie line was breached. With the fall of Bruges and Ostend, and the Belgian army exhausted, the king called for an armistice on the same day. The surrender resulted in the capture of substantial military material, including artillery tractors and T.13s, most of which were repurposed for German training and local defense.

In the early days of the war several Belgian Biplanes fought bravely against the advancing Luftwaffe with modified Italian and British designs, such as the CR.42, the Hurricane with 13.2 mm’s and the Gladiator Mk.1 with FN machine guns.

The most notable is the CR.42:

At the time of the invasion, only 22 CR.42s were available, and all were immediately deployed for airfield defense or reconnaissance missions. Losses began on the very first day. When an attack on Nivelles airfield was anticipated, the CR.42s were readied for action. As the planes began taking off, the first German Stukas appeared. At 04:15 on May 10th, the first two CR.42s were hit. The remaining aircraft managed to reach Brustem, from where they were meant to operate. However, just as the last three planes were preparing to land, a formation of German Ju 52s was spotted over Tongeren. The three planes engaged the formation, scoring enough hits to force one Ju 52 to land. The trio was soon attacked by enemy fighters but managed to escape unharmed.

Later that morning, five CR.42s took off from Brustem for another airfield defense mission. During this, pilots Charles Goffin and Roger Dellaney engaged in a dogfight with several Bf 109s. Dellaney was shot down, but Goffin successfully shot down a Bf 109E. Soon after, Lt. Werner de Mérode shot down a Do 17 while returning from a reconnaissance mission.

Next, a formation of Stukas attacked the airbase. The 4th Squadron had hidden their aircraft in a nearby orchard, but the 3rd Squadron had not, leading to heavy losses for the latter. All 14 aircraft of the 3rd Squadron were destroyed in the attack, leaving only the 8 CR.42s of the 4th Squadron operational. The remaining aircraft were moved to Grimbergen and Nieuwkerken-Waas on May 11th, before being redeployed to Chartres in France on May 16th, where they, alongside 8 remaining Fireflies, continued to defend the airbase.

Curiously, Fiat delivered four additional aircraft to the Belgian Air Force during this period, although one was lost en route and never arrived. The aircraft parts were rerouted to Bordeaux, where they were quickly assembled and deployed. However, the remaining Belgian CR.42s continued to suffer losses from air raids and were relocated to various airbases, eventually reaching Montpellier by the time of the French armistice. By August 27th, only five aircraft remained, which were seized by the armistice commission and handed over to the Germans. These planes were likely used as training aircraft.

Despite their short service of just six months, the CR.42s distinguished themselves by scoring at least five aerial victories, more than any other aircraft type in Belgian service during World War II.

5.2. Belgian armed forces in exile

During the war most Belgian units were integrated into British brigades, the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade, or the Free Belgian Forces. These units would start using more British and US equipment, which were mostly absent in the Belgian armed forces in the first stages of the war.

Belgian government officials gradually began to arrive in Great Britain, but the Belgian government in exile had difficulty gaining international recognition. However, thanks to income from Congo, the government was able to operate with some degree of independence. Minister Albert de Vleeschauwer played an important role in pushing for the continuation of the fight, and other ministers, such as Camille Gutt, Hubert Pierlot, and Paul-Henri Spaak, joined him. On October 31, 1940, a government in exile was formed. Since King Leopold III, as a prisoner of war, was unable to carry out his duties, the government took full legislative and executive power in December 1940. The government was later supplemented by Catholics Antoine Delfosse and August de Schryver, as well as the socialist August Balthazar.

Despite the fact that the government in London was unaware of the negotiations, the Belgian Union Minière struck a deal with the Americans for the supply of uranium from the Congolese province of Katanga, which was used to create the atomic bombs for Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

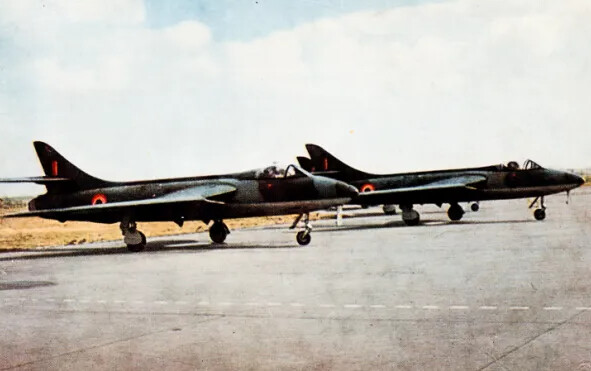

General Victor van Strydonck de Burkel began organizing Belgian troops in Great Britain in October 1940. Belgian pilots participated in the Battle of Britain and formed two squadrons: the 349th and the 350th. Around 600 Belgians were part of the naval personnel, and the Belgian merchant fleet, along with two corvettes (Godetia and Buttercup) and several minesweepers, flew the Belgian flag. This led to the re-establishment of the Belgian navy in February 1946, which had been disbanded in 1927 following the Locarno Pact.

Additionally, the Belgian 1st Infantry Brigade (the popular Piron Brigade) was established, consisting of about 1,800 men under the command of Colonel Jean-Baptiste Piron. They mostly used lend-lease US and UK-based equipment, such as the Staghound, Daimler Mark II, and the AEC. A small commando unit was also formed, which would later distinguish itself in Italy, Yugoslavia, and Walcheren, as well as a parachute unit that became part of the SAS brigade. Around 500 Belgians were dropped as agents by the SOE (Special Operations Executive) and SIS (Secret Intelligence Service). Of the 10,000 Belgians serving in Great Britain, around 2,500 were killed.

6. Post-WWII

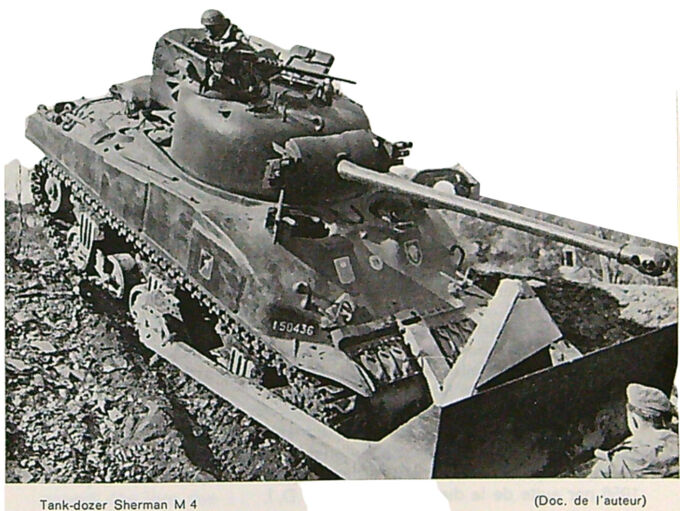

Right after WWII Belgium heavily relied on US and UK lend-lease and acquisitions to build its army, all recieved from 1945 to 1951:

The lessons of World War II highlighted the importance of collective security in Belgium’s foreign policy. In March 1948, Belgium signed the Treaty of Brussels and later became a founding member of NATO. Before NATO integration, Belgium and the Netherlands initiated the first binational agreement, laying the foundation for BeNeSam (the BeNeLux Admiralty), which remains a hallmark of regional naval cooperation.

Belgium’s integration into NATO’s armed forces accelerated following the Korean War. During the conflict, Belgium sent the Belgian Volunteer Corps to Korea, showcasing its commitment to international security. Subsequently, Belgium contributed a corps to NATO’s Northern Army Group, further solidifying its role in collective defense. The Belgian army would also buy a lot of US equipment to use in these conflicts.

Defense spending and military capacity grew significantly during this period. The army expanded from 75,000 personnel in 1948 to 150,000 by 1952. A comprehensive 1952 defense review established these ambitious goals:

- Three active divisions and two reserve divisions,

- A 400-aircraft air force,

- A 15-ship navy, and

- The creation of 40 anti-aircraft battalions equipped with radar and centralized command systems.

6.1. Belgium in Germany — Cold War — 1950s

The Belgian Forces in Germany (BSD) (French: Forces Belges en Allemagne) refers to the 'Belgian occupation force' in Germany after World War II; it was also the name given to the area where the forces were stationed. Located in what was then West Germany, the Belgian occupation force was deployed in the British occupation zone at the request of the Belgian government. These forces were under British command because they were part of the British sector of occupation.

Starting from April 1, 1946, three Belgian infantry brigades were stationed in Germany under British command, marking the beginning of the Belgian occupation units. Shortly afterward, the Belgian units were given their own area, known as the BSD, within the British occupation sector. This included a zone stretching from Aachen, Cologne, Soest, Siegen, and Kassel, largely covering North Rhine-Westphalia, which was under Belgian military control. A garrison was also stationed in Bonn until the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany on May 23, 1949. At that point, the commander of the Belgian forces (General Piron) had to vacate the buildings they occupied to make room for the government of the newly formed Federal Republic.

On April 4, 1949, NATO was founded, and on May 9, 1955, the Federal Republic of Germany became a NATO member. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact, which included the German Democratic Republic (GDR), had become the new common enemy. The term 'Belgian occupation force' had long since ceased to be accurate; by then, Belgium and Germany were working together within the framework of NATO, with the Federal Republic of Germany now part of the alliance. The Belgian forces remained stationed in the former occupation area, but their new mission was to help protect the Federal Republic and the West from a potential invasion by the Warsaw Pact. Close to the border with the GDR, there was a sense of unease among the military families, and plans were made to evacuate them to Belgium in the event of an invasion.

This area was also known as Belgium’s 10th province. Tens of thousands of Belgians, along with their families, lived there. By the early 1950s, there were 40,000 soldiers stationed in Germany, a number which had decreased to about 25,000 by the early 1990s. Following military reforms in Belgium, the armed forces in Germany were further reduced. The last barracks, in Troisdorf-Spich, was abandoned in June 2004. While a small number of Belgians remained active in NATO operations at the British barracks in Mönchengladbach, this base was also handed back to Germany in 2013.

6.2. Belgium in the Congo — 1960s

The Belgian-American relationship regarding Congolese independence was a curious mix of contradictions and similarities. The Belgians sought to preserve their colonial presence (in the form of 2 army bases) and the influence of Belgian interest groups in Congo, accusing the Americans of undermining this. At the same time, both countries shared a mutual dislike for the elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba—Americans feared he would push Congo toward the Soviet Union, while the Belgians saw him as an opponent of the interests of Belgian industrial and financial groups.

From May 1960, Belgium pursued an anti-Lumumba policy, influenced by a hard core within the Belgian government, which included Prime Minister Eyskens, Minister of Defense Gilson, Minister of Small Enterprises Vanden Boeynants, and most liberal ministers, who were most sensitive to the demands of former colonials and colonial interest groups. For Prime Minister Eyskens, Lumumba was a man “who must go,” according to Jef Van Bilsen.

Officially, Belgium supported a unified Congo, but due to Lumumba, Belgian African policy primarily focused on Katanga, where it engaged in a wide range of activities—economic, institutional, military, and diplomatic. This, however, strengthened the belief both within the Congolese government and the United Nations that Belgium was determined to maintain its presence in Katanga at all costs. The Belgian government spared no effort in trying to eliminate Lumumba’s influence. Through figures like Jef Van Bilsen, and diplomats Davignon and Westhof, Belgium first sought to convince President Kasavubu to dismiss Lumumba. Internal opposition to Lumumba, based in neighboring Brazzaville, was financially and materially supported.

The murder of Lumumba in mid-January 1961, however, completely removed the possibility of a government in Congo led by Lumumba, which Belgium feared. The support provided by Belgians in Lumumba’s arrest and transfer to Katanga, which led to his execution, and the subsequent approval of this by d’Aspremont Lynden, later led to suspicions that the Belgian government, if not directly responsible, was at least complicit in his murder through neglect.

6.3. 1960s-1980s

6.3.1. The Belgian Leopard 1 A1, the Gepard B2 and other equipment

In 1967, Belgium ordered 334 Leopard 1 A1 tanks (3rd and 4th production lots) to replace the M47 Patton. The Leopard 1(BE) is largely identical to its German counterpart but features modifications such as FN MAG machine guns, different stowage boxes, and, from 1974, a fire control system developed by SABCA/Cobelda (Compagnie belge d’électronique et d’automation). This system includes a laser rangefinder, an analog computer, and a crosswind sensor. These upgraded tanks are officially designated as “Leopard SCT” (Système de Conduite de Tir — fire control system). Ten of these tanks were later converted into training tanks, while nine served as the basis for the Leguan bridge-laying tank. These leopards served together with the Gepard B2 variant in the BSD. These Loepards were supplemented by M113 IFV’s, AIFV-B transports and a very large fleet of CVR (T) variants.

Between 1994 and 1997, 132 Belgian tanks were upgraded to the Leopard 1 A5(BE) standard. These upgrades included a new electro-hydraulic system, a muzzle reference system (MRS), and a modern fire control system from SABCA/OIP, equipped with a thermal sight located on the turret roof. The thermal sight allows a detection range of up to 8 km (identification range of 2 km), compared to the older white light/IR searchlight (XSW-30-U) with a range of only 1,200 m. Additionally, the Leopard 1 A5 received a new NATO three-color camouflage pattern. At least one tank received additional turret armor from Blohm & Voss (1A5BE 'MEXAS'), but this project was eventually discontinued.

6.3.2. 1989, a short overview

The Leopard 1 and its variants, along with other tracked vehicles like the M113A1-B, AIFV-B, and M109A2, were scheduled to be phased out of service by the Belgian Army by 2015. The Piranha DF90, DF30 and the DF30(spikes) will then take over as the primary weapon system and the most powerful combat vehicle in service.

6.4. Belgium in Rwanda

In the '80s and '90s, Belgium increasingly started to work together with other nations, and took part, in NATO deployments.

From October 1993 to March 1996, Belgium took part in UNAMIR, a United Nations peacekeeping mission aimed at ending the Rwandan genocide. During the mission, 10 soldiers from Belgium’s 2nd Commando Battalion were captured, tortured, and executed by the Rwandan Presidential Guard while they were assigned to protect the Rwandan Prime Minister. The murders were later investigated, and in 2007, Rwandan Major Bernard Ntuyahaga was convicted for his role in the killings.

6.5. Second Allied Tactical Air Force

Belgium was part of the SATF from 1958 until 1993. Mostly using its fleet of US and UK license-produced aircraft. These were mostly built by the Belgian Company SABCA in Brussels (like the F-16, Mirage 5BA and Alpha jet).

7. Post-Cold War

7.1. Budget cuts and specialisation

In 2001, the BeNeLux airspace convention was signed, where the Netherlands and Belgium would both patrol and share the airspace.

The Belgian defense industry would still have their hands in almost every project or vehicle that arrived in Belgium. Cockerill, SABCA, FN Herstal and Thales Belgium all were a part of most acquisitions by the Belgian army, navy and air force. Even if their central role in Belgian defence philosophy has by now been degraded a lot. e.g.: Cockerill is currently the world market leader in medium and light calibre tank guns and turrets, with over 2,500 pieces produced and exported between 2001 and 2016.

Belgium was also part of many UN and NATO missions in the 2000s and earlier: KFOR, SFOR, UNIFIL, Baltic Air Policing and more.

The modernisation project from 2008 finally transformed the Belgian army into a fully wheeled armored motorised force.

After the Cold War, Belgium significantly reduced its defense budget, leading to the retirement of more expensive vehicles in the military inventory. The Piranha IIIC was selected as the base platform for a variety of vehicles. An initial order for 138 units of different types was placed, and over time, this number grew. The fleet eventually consisted of the following vehicles: 99 Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) capable of transporting ten soldiers, 32 Fire Support Vehicles equipped with a 30mm weapon system, 40 Direct Fire Vehicles with a Cockerill 90mm cannon, 24 Command Vehicles, 12 Ambulances, 17 Repair and Recovery Vehicles, and 18 Engineer Vehicles.

7.2. Cooperations with other nations

Just like the afformentioned sharing of air-space defence between the Netherlands and Belgium, there have been several other major cooperation structures in the benelux military sphere, like in Special forces, troop air-transport, air traffic control, artillery training, etc. The oldest by far is the Benesam:

7.2.1. BeNeSam — BeNeLux Amirality

Belgian-Dutch naval cooperation began in 1948 with the BeNeSam agreement, which established joint naval operations in wartime. In 1962, a document allowed the appointment of an Admiral of Benelux, and by 1975, the Admiral Benelux was established during wartime. A major agreement in 1995 led to the integration of Belgian and Dutch naval staffs into a single command in 1996, with headquarters in Den Helder.

The cooperation covers various areas, including the operational management of M-frigates and mine countermeasure vessels. Belgium trains crews for the mine countermeasures, while the Netherlands handles the M-frigates. The binational Eguermin school in Ostend and training facilities in Zeebrugge and Den Helder support the collaboration.

In 2016, the partnership expanded to include the Belgian Light Brigade and Dutch Marine Corps, and joint naval procurement. Belgium will also provide personnel for the Dutch logistics support ship Zr.Ms Karel Doorman.

In June 2020, it was announced that the M-frigates would be replaced, with new ships focused on submarine warfare, expected to enter service between 2028 and 2030.

7.3. Towards the future

Today, the Belgian armed forces are going through a major modernisation programme, where every single vehicle outside from 2 patrol ships and some armoured recovery vehicles will be replaced by more numerous vehicles. Some of these vehicles include the French-built EBRC Jaguar, the Griffon and the Griffon MEPAC. Also some Dutch DAMEN and French built ships will come to the naval component, such as the Naval Group en Exail-built City/Vlissingen-class minehunters and the Anti-Submarine Warfare fregatten (ASWF). The F-35 will also make its first introduction in the Belgian Air Component soon.

8. Conclusion

Although small, the Belgian armed forces have a rich history of procurement of vehicles and battles, with a unique take of some fronts in domestic produced defence weaponry doctrine. Although it used to be rather large for its countries size, has now been reduced to a small professional armed force.

- Air Et Cosmos. Belgique : Retrait du service d’un premier C-130H. (n.d.). https://air-cosmos.com/article/belgique-retrait-du-service-dun-premier-c-130h-3204

- Dedonder, L. (18 June 2022). STAR-plan. https://dedonder.belgium.be/nl/star-plan

- Bernard Vanden Bloock, Belgian Fortifications, May 1940; Appendix B: Weapons, World War II Online — Technical Publications, 2003.

- Belgische Senaat, VERGADERING VAN MAANDAG 7 JULI 1997, VRAAG OM UITLEG VAN DE HEER GORIS AAN DE MINISTER VAN LANDSVERDEDIGING OVER DE LUCHTDOELDRONES VAN MISTRALRAKETTEN. (7th of july 1997). BELGIAN GOVERNMENT. https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=publications/viewPub&COLL=H&PUID=16777274&TID=16782439&POS=1&LANG=nl

- Belgian troops bid farewell to south Lebanon. (2016, October 18). UNIFIL. https://unifil.unmissions.org/belgian-troops-bid-farewell-south-lebanon

- Belgique : Retrait du service d’un premier C-130H. (n.d.). Air Et Cosmos. https://air-cosmos.com/article/belgique-retrait-du-service-dun-premier-c-130h-3204

- Courtial, V. T. L. a. P. M. (2021, April 8). La Belgique achète 4 drones MQ-9B Sky Guardian pour 159 millions d’euros. À L’Avant-Garde. https://defencebelgium.com/2020/08/17/la-belgique-achete-4-drones-mq-9b-sky-guardian-pour-159-millions-deuros/

- Courtial, V. T. L. a. P. M. (2022, June 5). Airbus livre un sixième A400M à la Belgique et au Luxembourg. À L’Avant-Garde. https://defencebelgium.com/2022/01/17/airbus-livre-un-sixieme-a400m-a-la-belgique-et-au-luxembourg/

- Decat, F. (2007). De Belgen in Engeland 40/45: de Belgische strijdkrachten in Groot-Brittannië tijdens WOII. Lannoo Uitgeverij.

- Destroy. (2014, October 24). Les chars belges en 1940 [Online forum post]. remember.forumofficiel.fr. https://remember.forumofficiel.fr/t257-les-chars-belges-en-1940

- De Flandre, F.-. L. (2024, July 4). Le général aviateur Frederik Vansina succède à l’amiral Hofman à la tête de la Défense. vrtnws.be. https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/fr/2024/07/04/le-general-aviateur-frederik-vansina-succede-a-lamiral-hofman-a/

- De Achttiendaagse Veldtocht. (n.d.). De Achttiendaagse Veldtocht. https://18daagseveldtocht.be/

- Draper, M. (2018). The Belgian Army and Society from Independence to the Great War. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Draper, M. (2018a). The Belgian Army and Society from Independence to the Great War. Springer.

- Egmont Institute. (2024, July 18). Back to the future: Applying Cold War wisdom to modern Belgian defence. https://www.egmontinstitute.be/back-to-the-future-applying-cold-war-wisdom-to-modern-belgian-defence/

- Grisard. (1982). Geschiedenis van het Belgisch leger van 1830 tot heden. Geschiedenis Van Het Belgisch Leger Van 1830 Tot Heden — Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent. https://lib.ugent.be/nl/catalog/rug01:000042552

- History of the 1st Belgian Group — Brigade Piron. (n.d.). http://www.brigade-piron.be/

- Karlsson, U. (2015, February 7), retrieved on 26 november 2024. Vilja, mod och uthållighet i Kongo. Smålandsposten. https://www.smp.se/artikel/vilja-mod-och-uthallighet-i-kongo/

- Laurent Halleux, Franck Vernier, Le V.C.L. T.13 B: Un nouveau type de véhicule au service des chausseurs Ardennais; Du tracteur d’artillerie au canon automoteur, Patrimoine Militaire, n.d.

- NATO. (n.d.) Belgium and NATO 1949. https://www.nato.int/cps/ge/natohq/declassified_162358.htm

- Nicholas Fiorenza. (16 May 2017). IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly. Military Capabilities — Belgium phases out Mistral. https://archive.ph/20170516223546/http://www.janes.com/article/70438/belgium-phases-out-mistral

- Onze missies. (n.d.). Defensie. https://www.mil.be/nl/onze-missies/de-benelux-qra/

- Pierre Muller, Les chasseurs de chars T.13: des armes défensives pour un pays neutre (1934-1940), Journal of Belgian History, XLIX, 2019, 1, pp. 64-80.

- Scorpion Reconnaissance Vehicle 1972-1994, Osprey Publishing Ltd, New Vanguard 13, 1995.05.15

- Schepens, L. (1980). De Belgen in Groot-Brittannië 1940-1944: feiten en getuigenissen.

- Staff, W. O. G. (2014). Handbook of the Belgian Army 1914.

- The Belgian commando troops. (n.d.). http://www.be4046.eu/Commando.htm

- Vanderstraeten, L. (1985). De la Force publique à l’Armée nationale congolaise: histoire d’une mutinerie, Juillet 1960.

- Vanden Bloock, B. (2003). Belgian Fortifications, May 1940; Appendix B: Weapons, World War II Online — Technical Publications, 2003.

- File: Belgium resources 1968.jpg — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Belgium_resources_1968.jpg

- Category: Naval ships of Belgium — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Naval_ships_of_Belgium

- 4de Infanteriedivisie | De achttiendaagse veldtocht. (n.d.). De Achttiendaagse Veldtocht. https://18daagseveldtocht.be/grote-eenheden/divisies/4de-infanteriedivisie/

- File: A T-13 B2 tank destroyer of the Belgian armed forces.jpg — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.-b). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_T-13_B2_tank_destroyer_of_the_Belgian_armed_forces.jpg

- War Hertitage Institute Belgium. (2025). Database pictures 1930s-1940s.

- Category: Renard aircraft — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Renard_aircraft

- 349 (Belgian) Squadron. (n.d.). Second World War / History | 349 (Belgian) Squadron. https://www.349squadron.be/history/second-world-war

- Category: Armoured cars of Belgium — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Armoured_cars_of_Belgium

- Category: Leopard 1 in Belgian service — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Leopard_1_in_Belgian_service

- Category: Belgian contingent of UNOSOM II — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Belgian_contingent_of_UNOSOM_II

- X.com. (n.d.). X (Formerly Twitter). https://x.com/defensie_be/status/822140507920990208

- File: F1Of6SiWCAAMKNA.jpg — Wikimedia Commons. (2023, July 17). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:F1Of6SiWcAAmKNA.jpg

- Gilbert, D. (n.d.-a). Belgian Mirage 5BA BA60, Paris Air Show 1993. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/2o5E4Vm

- Brigade Piron — Témoignages — Roger Dewandre. (n.d.). http://www.brigade-piron.be/temoignages_fichiers/tem_Dewandre.Roger.html

- Category: 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:1st_Belgian_Infantry_Brigade

- Category: Belgian Army in 1989 (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Belgian_Army_in_1989