The Battleship Bismarck is without a doubt the most iconic vessel ever built by the German Navy. Measuring an impressive 250.5 meters (822 feet) in length and 36 meters (118 feet) in width, with a maximum displacement of over 50,000 tons, it carried a crew of more than 2,000 sailors. Armed with eight 380 mm (15-inch) main guns and protected by heavy armor, the Bismarck was regarded as the most powerful battleship afloat at the time of its launch. She was also the lead ship of the Bismarck-class and, along with her sister ship Tirpitz, the largest German battleship ever.

Table of contents

Start of Construction

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from building capital ships. This restriction was lifted by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, which allowed the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) to construct battleships up to 35% of Royal Navy tonnage. The Bismarck was designed in the mid-1930s as a replacement for the aging SMS Hannover. Under contract “F”, construction began on July 1, 1936, at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg. 31 months later Bismarck was launched.

Ship Launching and Commissioning

On February 14, 1939, Bismarck was ceremonially launched in Hamburg in front of a crowd of over 60,000 people, with Adolf Hitler as honorary guest. After being christened by Dorothee von Löwenfeld, granddaughter of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, her namesake, the ship entered the fitting-out phase at Blohm & Voss, where her propulsion systems, additional armor, and eight 380 mm (15-inch) main guns were installed. Sea trials began in August 1940 to evaluate her speed, maneuverability, and weapon systems. On August 24, 1940, Bismarck was officially commissioned into the Kriegsmarine and conducted her first operational trials in the Baltic.

Following tests in various regions, she returned to Hamburg on December 9, 1940. Early the next year, Bismarck received orders to sail to Kiel, arriving there on March 9, 1941. From Kiel, she was escorted to Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland) by the icebreaker SMS Schlesien, where she remained until May 18, 1941, when she departed on her first — and only — combat mission, Operation Rheinübung.

Operation Rheinübung

On May 1, 1941, Hitler inspected the Bismarck. Though he remained silent during briefings, he was aware of the Royal Navy’s superiority and feared that the battleship might be lost. To prevent him from cancelling the mission, he was not informed of Bismarck’s sailing date until it was already four days past, which was on May 18, 1941.

On this day, Operation Rheinübung commenced with Bismarck, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, destroyers Z10, Z16, and Z23, and several smaller escort vessels. Their objective was for Bismarck and Prinz Eugen to break into the Atlantic and interdict Allied convoys headed towards the United Kingdom — replicating the success of the earlier Operation Berlin — to sever Britain’s supply lines and force it toward capitulation.

By this time, Bismarck’s crew had grown to over 2,200 sailors — most of them young men in their twenties, with some as young as 18. The crew was organized into twelve companies, each consisting of around 150 to 200 men and specializing in different duties, such as gunnery, engineering, communications, or damage control. Each company was further divided into at least two sub-units to improve coordination and efficiency aboard the massive battleship. The highest-ranking officers aboard were “Kapitän zur See” Ernst Lindemann, Bismarck’s commanding officer, and Admiral Günther Lütjens, who served as the fleet commander of the Kriegsmarine and was responsible for overseeing the entire operation. He also lead Operation Berlin before.

Before reaching the Atlantic, however, the squadron had to transit the Baltic and North Sea. While passing through the Kattegat between Denmark and Sweden, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were spotted by the Swedish aircraft carrier Gotland, which relayed a routine report noting “two German ships” without specifying their identities. On May 21, the Admiralty received this information via spies within the Swedish government and intensified reconnaissance to determine whether Bismarck was involved. Anchored in a Norwegian fjord near the city Bergen after the destroyers detached, Bismarck was photographed by a Spitfire reconnaissance plane — prompting the Royal Navy to scramble forces quickly to prevent her escape into the Atlantic.

Since the English Channel was ruled out from the start, because Bismarck would have been constantly visible to the British and thus vulnerable, Lütjens had three possible routes into the Atlantic. The most direct but risky option was the Fair Isle Channel through the northern British Isles, however, there British aircraft from mainland Scotland could easily intercept the ships. A second route ran south of Iceland, but this area was heavily patrolled by British cruisers and destroyers.

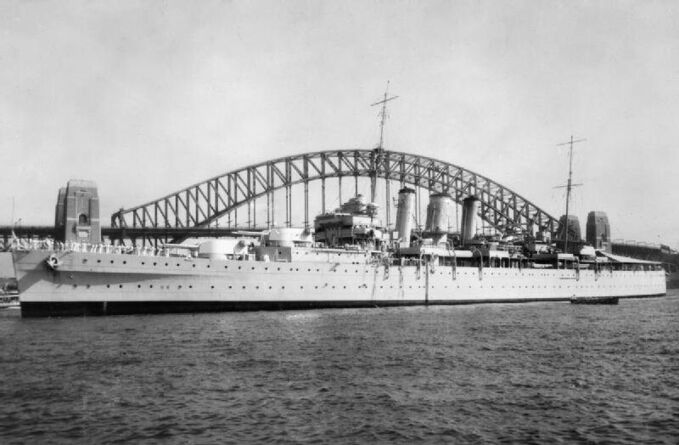

Ultimately, Lütjens chose the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland. Because the British did not know his exact plan, they had to guard both the southern and northern approaches to Iceland. In the south, they stationed cruisers such as the HMS Birmingham and HMS Manchester and destroyers, while in the north — at the Denmark Strait — the battlecruiser HMS Hood and battleship HMS Prince of Wales, along with the heavy cruisers HMS Norfolk and HMS Suffolk (already on station), awaited the Bismarck. Additional ships were also mobilized to intercept the German squadron, including HMS King George V and HMS Repulse.

The Battle of the Denmark Strait

On the evening of May 23, 1941, HMS Suffolk, patrolling northwest of Iceland, detected the two large German warships on her radar near Greenland’s coast and immediately alerted the Admiralty. HMS Norfolk, trailing slightly behind, acquired contact moments later. As the German ships approached within approximately 10 km (6 miles), Bismarck opened fire. However, both ships were not hit and disappeared into the fog, continuing to shadow the German force by radar.

The following morning at 05:52 a.m., HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales made contact with the German ships. Hood, leading the British battle line, opened fire on the flotilla’s lead ship from about 23 km (14 miles), followed closely by Prince of Wales. However, firing her main batteries at Norfolk had knocked out Bismarck’s radar earlier, so Admiral Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen to take the lead. This maneuver drew Hood’s initial salvos toward Prinz Eugen, buying Bismarck precious time to respond.

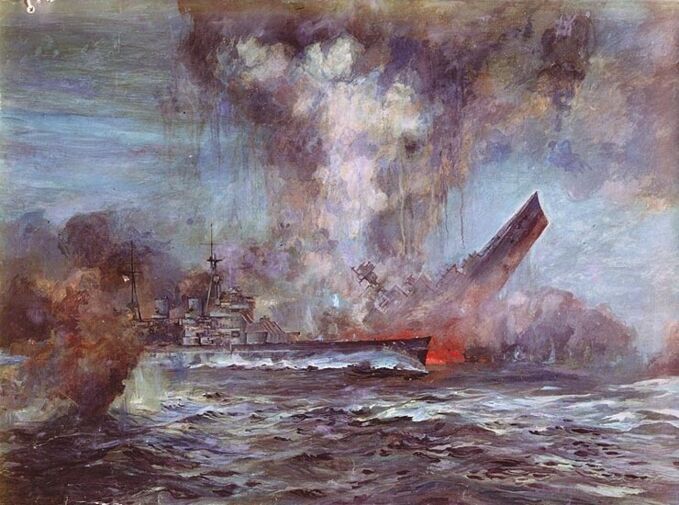

However, despite the urgent situation, Admiral Lütjens initially withheld permission to return fire. Captain Lindemann, frustrated by the delay, reportedly insisted several times, and when Lütjens still refused, Lindemann is said to have declared, “I will not let my ship be shot out from under my ass,” and ordered Bismarck to open fire on his own authority. Both German ships then targeted Hood, and a salvo from Prinz Eugen ignited a fire on the British battlecruiser. Around 06:00 a.m., Bismarck’s fifth salvo struck Hood’s aft magazines, causing a catastrophic explosion that tore through and sank her within three minutes. Of her crew of 1,418, only three men survived. In less than ten minutes, HMS Hood, once the pride of the Royal Navy and recently upgraded, was lost.

Meanwhile, Prince of Wales, despite suffering damage, managed to land three shells on Bismarck’s hull before retreating under heavy fire behind smoke cover. While these hits did not significantly reduce Bismarck’s capabilities, they caused flooding in a forward compartment and triggered a serious oil leak. Captain Lindemann wished to pursue and finish off Prince of Wales, but Admiral Lütjens overruled him, adhering to strict orders from the German “Oberkommando der Marine” (Naval High Command) to avoid any unnecessary or prolonged engagements with the Royal Navy. (“The primary mission of this operation […] is the destruction of the enemy’s shipping; enemy warships will be engaged only when primary mission makes it necessary and it can be done without excessive risk.”)

In the end, Prince of Wales was hit seven times — four times by Bismarck and three by Prinz Eugen. Bismarck was struck three times by Prince of Wales, while Prinz Eugen remarkably did not suffer any damage.

Recognizing that the damage sustained, especially the critical oil leak, made further raiding impossible, Lütjens ordered a course change toward Brest on the occupied French coast. HMS Norfolk and HMS Suffolk continued to shadow Bismarck from a distance using radar, relaying her position to the Home Fleet. This set in motion the relentless pursuit that would ultimately lead to Bismarck’s final battle.

The British Pursuit

While the destruction of the “Mighty Hood” fueled propaganda in the Third Reich, portrayed as proof of Nazi naval supremacy and earning Lütjens and Lindemann the Knight’s Cross, the Admiralty’s reaction was both shock and fury. Hood’s sinking, given her status as a symbol of British naval power, also stunned the British public. Furthermore, this blow came at a low point in the war: Britain stood alone against Hitler, London endured nightly bombings, and the campaign in Egypt against Rommel was faltering.

Upon learning of Hood’s loss, Churchill wrote: “At about seven, I was awakened to hear formidable news. The Hood, our largest and also our fastest capital ship, had blown up. Although somewhat lightly constructed, she carried eight 15-inch guns and was one of our most cherished naval possessions. Her loss was a bitter grief. […]”

Within hours of Hood’s loss, determined to avenge one of their greatest defeats and in a last ditch effort to protect vital supply lines, the Royal Navy dispatched over 40 ships — including four battleships, two battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, three heavy cruisers, ten light cruisers, and twenty-one destroyers — to hunt down the German battleship. “Sink the Bismarck!” became a literal battle cry for the Navy the following days.

After being shadowed by HMS Suffolk, HMS Norfolk, and HMS Prince of Wales throughout May 24 at a range of around 28 km (17 miles), Bismarck came under air attack that evening, at approximately 23:33, from Fairey Swordfish torpedo-bombers from the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious. Despite their persistence, the aircraft failed to inflict any damage, scoring only near misses that wounded six crewmen and killed one. Lütjens then used the cover of darkness and fog to avoid further attacks, ordering a course change shortly after 3 a.m. on May 25 that shook off the pursuers. By now he had already decided to dismiss the Prinz Eugen from the formation and sail alone toward the French coast.

For the next hours, Royal Navy vessels — having lost her position — started searching for Bismarck. It was not until about 09:30 a.m., that Lütjens, unaware that the British had lost track of him, broke radio silence with a series of coded reports to Germany. Radio direction-finding stations in Britain and Ireland intercepted his signals, determined his position, and sent the bearings HMS King George V. However, the navigation officer made an error, so the battleship changed course and headed at full speed in the wrong direction.

Now the Bismarck was almost out of reach. By nightfall on May 26 she would be within protective range of the Luftwaffe. By the next morning, she would be in safe waters.

On May 26, however, at approximately 10:52 a PBY Catalina flying boat detected the battleship. This started a series of aerial attacks, because the only force with any hope of stopping her, were the Swordfish torpedo bombers on HMS Ark Royal, since the Bismarck, despite her damage, was still too fast for the other ships to catch up.

The first attempt, launched at 3 p.m. nearly led to disaster, as the planes mistook the light cruiser Sheffield for the enemy. After refueling and rearming they launched again, only four hours later — 15 aircraft in three flights. Due to heavy winds and thick clouds, they did not manage to inflict damage on Bismarck again.

After failing again, the last flight of five Swordfish attacked at around 20:50, dropping their torpedoes from an altitude of about 15 meters (50 feet) and leading Bismarck by a standard two ship-lengths with their aim. This was their last chance to slow down Bismarck, if the attack would fail, so would the entire operation.

Miraculously, Lindemann took an evasive maneuver, turning hard to port. Due to this, a torpedo hit the ship in the only real vulnerable place, the stern, jamming the rudder at 12 degrees and putting the ship into a continuous counterclockwise turn. The rudder would not budge, and the crew was unable to cut it free with underwater saws. Upon realizing their fate, with maneuverability lost and the Royal Navy now closing in, the crew made preparations for their final engagement.

The Final Stand

After an attack by the 4th British destroyer flotilla during the night failed to score any hits due to poor weather, Bismarck’s adversaries returned the following morning. At approximately 08:47 a.m. on May 27, HMS Norfolk, HMS King George V, and HMS Rodney closed in on Bismarck. Rodney opened fire first, scoring a crippling hit on one of Bismarck’s gun turrets within minutes. Bismarck retaliated and managed to damage Rodney’s superstructure, but shortly afterward King George V put Bismarck’s last operational fire-control director out of action. Without central fire coordination, Bismarck’s remaining gun turrets were knocked out one by one, rendering the battleship combat incapable. Recognizing their hopeless situation, the order was given to scuttle the ship.

The crew then set demolition charges in the engine rooms, nine minutes later, these charges blasted open the seawater-cooling outlets on the hull’s underside. Simultaneously, watertight doors along the propeller shaft tunnels were opened to flood Bismarck rapidly. As King George V withdrew to British waters to resupply fuel, HMS Dorsetshire closed the range, opening fire at 09:40 a.m. By that time, Bismarck was already engulfed in flames and stern-heavy, yet her main armor belt remained largely intact. Dorsetshire launched three torpedoes that struck the stern, ensuring Bismarck could no longer stay afloat.

After the British had fired over 2,876 rounds and Bismarck had endured more than one and a half hours of combined fire and own scuttling efforts, she finally sank at 10:40 a.m. on May 27, 1941 approximately 1,000 km (621 miles) of the french coast. The Royal Navy immediately began rescue operations, but a reported U-boat sighting — later proven false — forced many ships, including Dorsetshire, to abandon survivors. Of Bismarck’s complement of over 2,200 sailors, only 116 were ultimately rescued. Nearly 2,100 men perished, including Captain Lindemann and Admiral Lütjens, having already been killed earlier by a grenade detonation in the conning tower.

The Aftermath

The destruction of the Bismarck dealt a severe blow to Nazi Germany, both strategically and symbolically as it was one of their first major defeats of the war. Although Nazi propaganda framed the loss as a heroic sacrifice, emphasizing the ship’s prior victory over HMS Hood and the bravery of its crew, the truth was far more grim. The announcement of the Bismarck’s sinking came only days later, carefully worded to maintain public morale. While Admiral Lütjens and Captain Lindemann were portrayed as national heroes, the regime avoided dwelling on the catastrophic defeat. The full extent of the loss — over 2,000 sailors and Germany’s most powerful warship — remained obscured from the general public.

Behind closed doors, however, the reaction was very different. Hitler was furious. The sinking of the Bismarck confirmed his long-standing distrust of surface ships. From that point on, German naval strategy shifted decisively toward submarine warfare. Capital ships like the Tirpitz were mostly kept in port or used for deterrence, never again for such operations.

The loss also had a psychological impact on the Kriegsmarine. The Bismarck had been a symbol of naval pride and technological prowess. Its destruction shattered the illusion of German dominance at sea. From then on, the U-boat campaign became the central pillar of Germany’s efforts to cut Britain off from vital supplies, marking a turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_battleship_Bismarck

- https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bismarck_(Schiff, _1940)

- https://www.kbismarck.com/operheini.html

- https://winstonchurchill.org/publications/finest-hour/finest-hour-177/churchill-royal-navy-bismarck/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Rheinübung

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/HMS-Hood

- https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/in-pursuit-of-the-bismarck/

- https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-12171

- https://m.ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=19