The Mitsubishi A6M Reisen, also known as the Navy Type 0 carrier fighter (零式艦上戦闘機, Rei-shiki-kanjō-sentōki), is a carrier-based fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to 1945 and was usually referred to by Allied pilots as the "Zero", even though its reporting name was "Zeke".

Design, Development and Variants:

In early 1937, as the Mitsubishi A5M entered service, the Imperial Japanese Navy began planning for its future replacement. In October of the same year, the Navy sent preliminary fighter requirements to Nakajima and Mitsubishi, asking for designs capable of much greater performance. After gaining combat experience in China, the Navy revised their expectations: the new fighter needed to reach 270 knots (310 mph) at 4,000 meters, climb to 3,000 meters in under 10 minutes, have long range with drop tanks, and carry heavy armament consisting of two 20 mm cannons, two 7.7 mm machine guns, and two 60 kg bombs. It also had to be compact enough for carrier operations and at least as agile as the A5M.

Finding these demands unrealistic, Nakajima dropped out. Mitsubishi’s lead designer, Jiro Horikoshi, believed it was possible, but only by making the aircraft as light as he could. His team used a new, lightweight aluminum alloy called “extra super duralumin”, which was strong but vulnerable to corrosion, though this was countered with a protective coating. To keep weight down, the Zero had no armor or self-sealing fuel tanks, trading survivability for speed, range, and agility. Even though these characteristics eventually led to the Zero’s demise, it is important to note that this was common practice when designing aircraft at the time, meaning that the A6M did not lag behind designs from other nations.

The finished design was a sleek low-wing monoplane with retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit, cutting-edge technology for its time. Its low weight and large wing area gave it excellent low-speed handling and exceptional maneuverability, easily out-turning Allied fighters early in the war. Early production models even had servo tabs on the ailerons to ease high-speed controls, though these were later removed to prevent pilots from overloading the wings.

The fighter’s official designation was A6M: “A” for carrier fighter, “6” for the sixth model, and “M” for Mitsubishi. It became widely known as the “Zero”, referring to the year 2600 (1940) in the Japanese calendar. Japanese pilots often called it “Zero-sen” (Reisen). The Allies nicknamed it “Zeke” under a system of using male names for enemy fighters. Variants like the floatplane A6M2-N were called “Rufe”, and a modified A6M3 model was initially named “Hap” before being changed to “Hamp” after complaints from General “Hap” Arnold.

Variants:

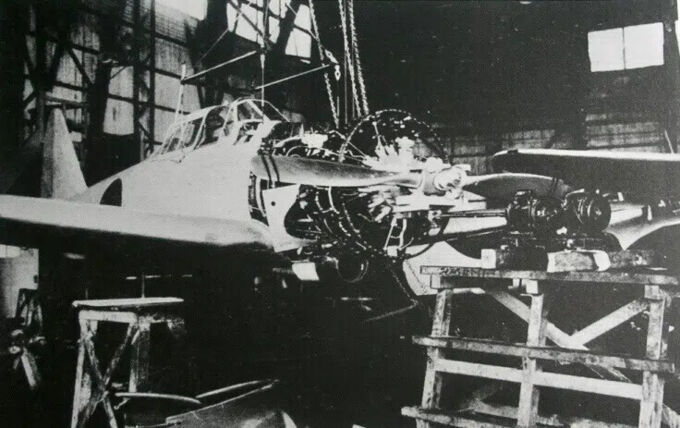

- A6M1: The first two prototypes, fitted with 780 hp Mitsubishi Zuisei engines. They had poor performance, leading to a switch to a more powerful engine. Only 2 built. (Image Source)

- A6M2 Model 11: Early production model with a more powerful Nakajima Sakae 12 engine (940 hp). Fixed wings without folding tips. About 64 produced. (Image Source)

- A6M2 Model 21: An improved Model 11 with folding wingtips for better carrier storage. This version fought at Pearl Harbor. Around 740 built by Mitsubishi, plus 524 by Nakajima. (Image Source)

- A6M3 Model 32: Shorter wings without folding tips for better roll rate and stronger airframe, powered by the Sakae 21 engine (1,130 hp). Had reduced range, which was a major flaw. About 343 built. (Image Source)

- A6M3 Model 22: Tried to fix Model 32’s problems: restored longer wingtips and added more fuel tanks for greater range. Around 560 built. (Image Source)

- A6M4 Model 41/42 (Experimental): Intended to have turbo-supercharged engines for high-altitude performance, but the project didn’t succeed. Only prototypes built, no mass production. (Image Source)

- A6M5 Model 52: One of the most important versions: stronger wings, no folding tips, better speed and diving ability. Several subvariants (like Model 52a, 52b, and 52c) with small improvements in armament and protection. Mitsubishi built 5,491. (Image Source)

- A6M6 Model 53: Experimental version trying to introduce self-sealing fuel tanks and stronger structure. Very few were built before switching to the A6M7.

- A6M7 Model 62/63: A dive bomber version for kamikaze attacks, with reinforced wings and bomb racks. Also added some pilot armor. Produced in small numbers. (Image Source)

- A6M8 Model 64: Final attempt to modernize the Zero with a 1,560 hp Kinsei 62 engine and much better protection. Two prototypes were built in 1945, but it never entered production. (Image Source)

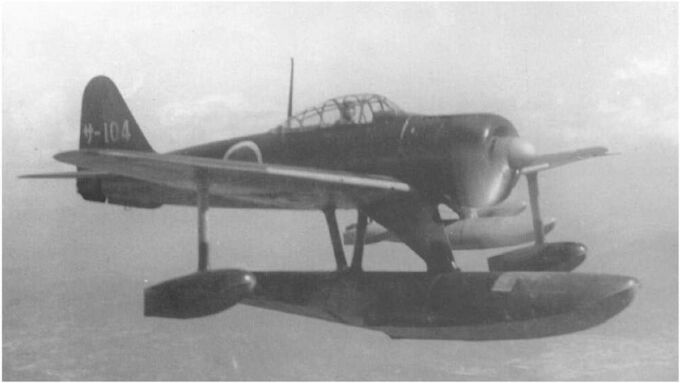

- Nakajima A6M2-N: A floatplane fighter based on the Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 11 produced by Nakajima. The Allied reporting name was Rufe. (Image Source)

Operational History:

The A6M2s were the first variants of the Zero to enter service. It first saw combat in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, escorting bombers and taking part in air combat, gaining a formidable reputation. The aircraft quickly earned respect for its lightweight design, impressive maneuverability, and exceptional range, which far exceeded contemporary Western fighters.

At the time of its introduction, the A6M could outperform virtually any aircraft it encountered, and its armament of two 20 mm Type 99 cannons and two 7.7 mm machine guns made it deadly in dogfights. Its dominance during these early operations demonstrated the success of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s philosophy, which emphasized range and agility at the cost of armor and self-sealing fuel tanks.

The Zero’s most iconic moment came during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, where they escorted bombers and strafed ground targets. Following Pearl Harbor, the aircraft participated in Japan’s invasion of the Pacific and Asia, including actions over the Philippines, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, and Burma. The Zero took part in significant battles of the Pacific War, such as the Battles of the Coral Sea, Guadalcanal, Santa Cruz, and others. In the early months of the conflict, Allied pilots were largely unprepared for the Zero’s capabilities. Conventional tactics like turning dogfights proved disastrous against the Zero’s superior maneuverability.

It was also on the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor that the Nakajima A6M2-N, known to the Allies as the Rufe, a floatplane adaptation of the Zero, flew for the first time. It was developed by the Nakajima Aircraft Company as a stopgap solution for the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, addressing the need for fighter aircraft capable of operating from water in areas lacking airfields. Nakajima modified the A6M2 Model 11 into a floatplane by replacing its landing gear with a large central float and two stabilizing wing floats. To preserve flight characteristics, the tail was adjusted, and the central float included a fuel tank to offset the loss of a drop tank. Though slower and less agile than the land-based Zero, the A6M2-N retained good range and maneuverability for a floatplane. Despite initial plans for 500 units, only 327 were built due to changing wartime priorities.

In June 1942, the US military captured an A6M that made an emergency landing in Akutan Island, in the Aleutian Islands. A thorough study of this aircraft revealed that while the Zero had excellent turning and climbing capabilities, it had problems with rollover and diving performance at high speeds. As a result, the US military issued a set of recommendations known as the “Three Nevers” to all pilots who expected to engage in air combat with a Zero fighter: “Never engage in dogfights with a Zero”, “Never engage in fights with a Zero at speeds below 300 miles per hour unless you can get behind it” and “Never pursue a Zero that is climbing”.

The Aleutian Islands were also one of the locations where the A6M2-N saw its earliest deployments. It flew reconnaissance, interception, and harassment missions against US forces despite harsh weather and limited infrastructure. The Rufe operated effectively from bays and inlets, supporting Japanese efforts to maintain control over the islands of Kiska and Attu.

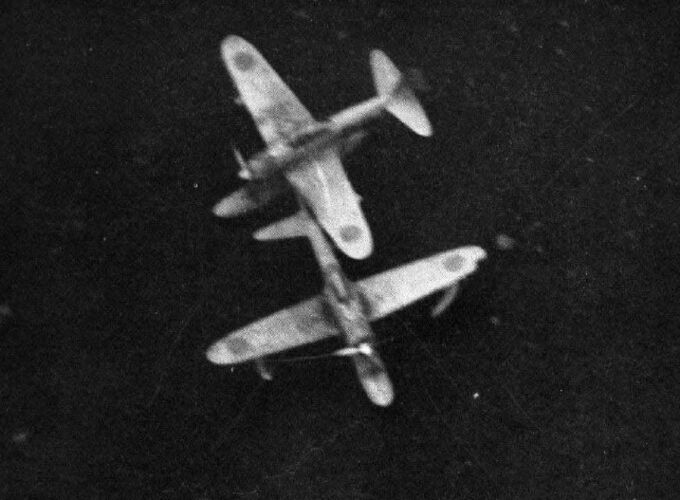

To counter the Reisen’s agility, Allied pilots began to employ hit-and-run tactics such as “boom and zoom” from superior altitudes as well as the formation tactic known as the “Thach Weave”, in which two or more allied planes wove in regularly intersecting flight paths to lure an enemy into focusing on one plane, while the targeted pilot’s wingman would come into position to attack the pursuer. The eventual arrival of newer Allied aircraft like the F6F Hellcat, the F4U Corsair, and the P-38 Lightning, with their better speed, armor, and firepower, also began to tilt the balance.

Over the years, new variants of the Reisen were introduced. The A6M3 Model 32 featured clipped wings which gave it a better roll rate, but reduced range, which disappointed Japanese commanders. It gave way to the Model 22, which restored the longer wings and folding tips, regaining range. Later in the war came the A6M5, with a shorter wingspan and stronger wings which made the Zero faster and allowed a higher diving speed. Some later variants were developed, but they never reached full-scale production.

Both the carrier-based and the floatplane versions of the Reisen saw service in the Solomon Islands, where they attempted to defend Japanese positions during the Guadalcanal campaign. However, both of the aircrafts' vulnerabilities became apparent. On August 7, 1942, during a surprise attack carried out by F4F Wildcats from the aircraft carrier USS Wasp, nearly all stationed A6M2-Ns were destroyed on the water or during takeoff.

In New Guinea, these fighters provided limited cover for Japanese transports and outposts, with Rufes often operating from seaplane bases hidden along jungle rivers or coastlines, but as the war progressed, the Rufe struggled to compete with newer Allied fighters, leading to its gradual withdrawal from front-line service. Production ceased in September 1943. Postwar, a single A6M2-N was captured by French forces in Indochina and briefly operated by the French Navy before crashing.

As the Zero neared the end of its dominance, the Japanese Navy attempted to replace it with the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden and the Kawanishi N1K Shiden. However, delays and technical problems in both designs meant the Navy had to rely on upgraded versions of the Zero, sacrificing its famed maneuverability in exchange for heavier armament and better protection. This made it less effective against new Allied aircraft, which increasingly dominated aerial combat from 1943 onward. Even though the A6M was hopelessly outdated at this point, its replacement, the A7M Reppu, never entered mass production.

Pilot quality, which was excellent at the start of the war thanks to experience gained in China, also deteriorated sharply, mostly due to the loss of skilled pilots in battles such as Midway or Guadalcanal, as well as a rushed and inadequate training due to Japan not being capable of consistently replacing the losses. Poor command decisions, such as the refusal to prioritize air combat training worsened the situation, culminating in units being wiped out in their first engagements. That being said, skilled Japanese veterans could still score occasional victories.

By 1944, during battles such as the Mariana Islands campaign and the Battle of the Philippine Sea (sometimes called the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”), Zeros suffered catastrophic losses against better-trained American pilots flying superior aircraft.

On November 27, 1944, 12 Zero fighters, guided by two C6N Saiun reconnaissance planes, led a surprise attack attack on Isley Field, in Saipan, where B-29 Superfortresses were stationed. The attack was a success, and starting at 10:40 AM, the A6Ms strafed the B-29s lined up on the ground three times, resulting in four blowing up or burning, six being destroyed, and 23 damaged. The Zeros continued their attack until the very end, but were shot down by intense anti-aircraft fire and P-47s that intercepted them. Only one Zero survived.

In the desperate final stages of the war, the Zero took on a new, grim role. It became one of the primary aircraft used in kamikaze missions, suicide attacks where pilots would deliberately crash into enemy ships. Lightly built and capable of carrying a significant explosive payload, the Zero was well-suited for this role, although this tactic saw little success, and only came to fruition as a result of Japan’s increasingly dire situation rather than an attempt at obtaining tactical advantage.

During the battle of Okinawa, 602 Zeros were deployed for a kamikaze strike, of which 320 did not return. The US Navy suffered heavy losses in the Battle of Okinawa due to kamikaze attacks, with 36 ships sunk and 368 damaged, 4,907 men killed and 4,824 wounded on board.

The Zero continued to fly missions until the very end of the war. On August 15, 1945, Zero fighters intercepted American and British aircraft in one final large-scale battle. It is said that it was also a Zero that attacked an American B-32 Dominator bomber on August 17 after the end of the war. Although the B-32 was hit, it was not shot down, but Sergeant Anthony Marchionne became the last American soldier to be killed in action in World War II.

At the end of the war, 1,166 Zeros survived. All the remaining aircraft were scrapped, except for those taken by Allied forces for testing purposes. Few aircraft remain in perfect condition in Japan, but there are several scrapped aircraft and aircraft restored from wreckage that are on display in the country.