When the Soviet Navy needed to replace their aging Svetlana-class and Admiral Nakhimov-class cruisers, they recognized a lack of expertise and infrastructure to construct large cruisers independently. As a result, they sought foreign assistance to design and build a new light cruiser. This new vessel would later serve as an influential model for Soviet shipbuilders to develop more advanced cruisers in the future.

Design

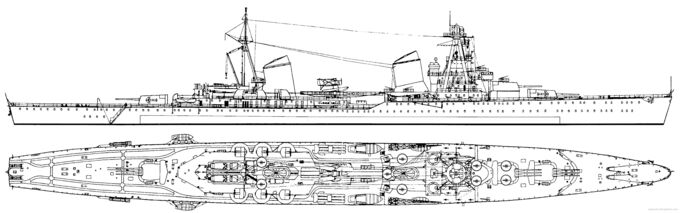

In 1933, the Ansaldo company provided blueprints for the Raimondo Montecuccoli, a Condottieri-class cruiser, and proposed redesigning it to accommodate six 180mm guns in a twin-turret configuration. However, the turret designer successfully persuaded the lead designer to fit three triple-gun turrets on the ship while maintaining the specified weight limit. This innovative adjustment ultimately resulted in the approval of the design, which became known as Project 26.

The first Project 26 ship was laid down in 1935 and completed in 1938. This lead ship of the class was named Kirov after Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a prominent Soviet political figure. The second ship of the class, Voroshilov, was named after Kliment Voroshilov, a Marshal of the Soviet Union. Although Voroshilov was laid down one week earlier than Kirov, it was not completed until 1940 due to difficulties in providing resources and materials to the southern Ukrainian SSR.

When first commissioned in 1938, Kirov was the most powerful light cruiser in the world. This was due to her three triple 180mm main guns, capable of penetrating more than 200mm of armor at long distances. Her main guns were comparable to the heavy cruiser armament of other nations during that era. In addition to her formidable main battery, she was equipped with six single 100mm dual-purpose guns, six single 45mm anti-aircraft guns, four single 12.7mm machine guns, two triple 533mm torpedo tubes, as well as sea mines and depth charges. Despite this extensive armament, Kirov maintained impressive speed and maneuverability, albeit at the expense of relatively lighter armor compared to other light cruisers of her time.

Sub-classes

With the completion of the first batch of Kirov-class cruisers (the Kirov and Voroshilov), the head designer recognized potential for further improvements, particularly in increasing anti-aircraft capabilities. After some redesigns, they were able to add three more single 45mm anti-aircraft guns, bringing the total to nine. This led to the creation of the second batch of Kirov-class cruisers, which was designated as Project 26bis. The first ship of this batch was completed in the late 1940s and was named Maxim Gorky after Alexei Maximovich Peshkov, a renowned Russian writer and political thinker. The second ship of the second batch, Molotov, was completed in 1941 and named after Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov, a prominent Soviet politician and diplomat.

The third batch of Kirov-class cruisers introduced significant changes to their secondary armament. The first ship of this batch, Kalinin, was completed in 1942 and named after Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin, a prominent Soviet political leader. Unlike earlier ships, Kalinin did not use six single 100mm dual-purpose guns. Instead, she was equipped with eight single 76mm dual-purpose guns, along with six single 45mm anti-aircraft guns, six single 12.7mm machine guns, and ten single 37mm anti-aircraft guns.

The second ship of the third batch, Kaganovich, was completed in 1944 and named after Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, another influential Soviet political figure. Kaganovich further differed from the earlier Kirov-class cruisers, as she did not carry six single 100mm or eight single 76mm dual-purpose guns. Instead, she was armed with eight single 85mm dual-purpose guns. Her lighter armament was identical to Kalinin, consisting of six single 45mm anti-aircraft guns, six single 12.7mm machine guns, and ten single 37mm anti-aircraft guns.

Despite their differences in armament layout, Kalinin and Kaganovich shared the same designation: Project 26bis2.

Service History

Kirov

Commissioned into the Baltic Fleet in 1938, Kirov saw limited activity before the outbreak of World War II.

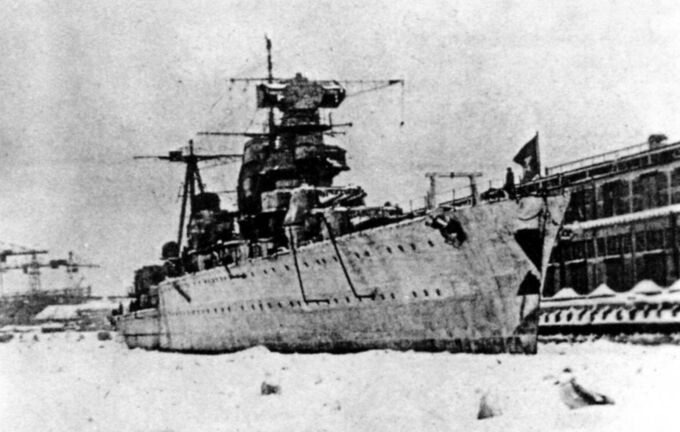

During the Winter War, Kirov, escorted by two destroyers, attempted to bombard Finnish coastal defenses at Russarö on 30 November. However, she was damaged by near misses from Finnish artillery and withdrew for repairs, remaining out of action for the rest of the conflict. At the onset of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Kirov was trapped in the Gulf of Riga. She supported Soviet minelaying operations before navigating the shallow Moon Sound Channel to reach Tallinn. There, she provided gunfire support during the defense and subsequent evacuation of Tallinn to Leningrad. For much of the war, however, Kirov was blockaded by Axis minefields in Leningrad and Kronstadt.

During this period, Kirov endured repeated German air and artillery attacks, suffering severe damage in April 1942. Repairs were extensive and included significant upgrades to her anti-aircraft defenses. Following the liberation of Leningrad in 1944, she briefly participated in the Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive but did not see further active combat.

After the war, Kirov underwent extensive refits, including the replacement of her radars, fire control systems, and anti-aircraft weaponry with the latest Soviet technology. She remained in service with the Baltic Fleet until her decommissioning and subsequent scrapping in 1974.

You still can find the remains of the Kirov’s first and second main turret in Saint Petersburg as a monument.

Voroshilov

Voroshilov was commissioned into the Black Sea Fleet upon her completion in 1940. Shortly after the start of Operation Barbarossa, she supported the destroyers during the Raid on Constanța, where she sustained minor damage from a mine. Following this operation, Voroshilov continued to bombard Axis positions near Odessa before being transferred to Novorossiysk. While in harbor, she was struck twice by bombs dropped by Junkers Ju 88 bombers, with one hitting her third turret and necessitating repairs. She was towed to Poti, where repairs were completed in early 1942.

After returning to service, Voroshilov resumed shelling Axis positions near Feodosia but was again damaged by bombing raids from Ju 88s, requiring further repairs in Batumi. By mid-1942, she provided fire support for Soviet forces around Kerch and the Taman Peninsula. In late 1942, while bombarding Zmiinyi Island alongside Soobrazitelny, Voroshilov struck a Romanian mine but managed to return to Poti under her own power for repairs.

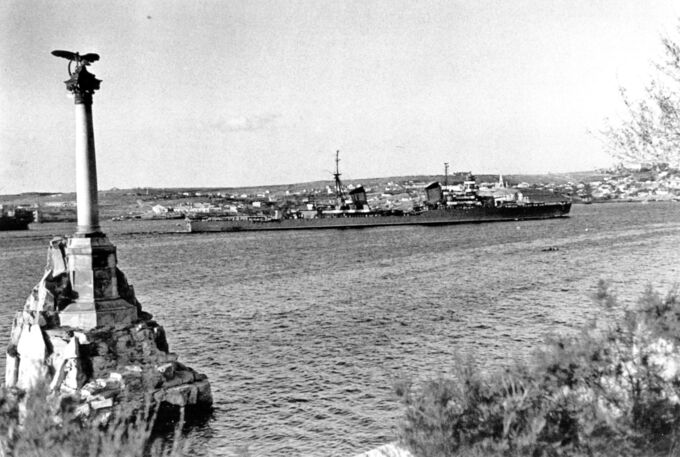

Repairs were completed in early 1943, after which Voroshilov supported Soviet troops landing behind German lines at Malaya Zemlya. Following this, her active combat role ended due to a direct order from Stalin prohibiting the use of large naval units without his express permission. This restriction was imposed after three destroyers were lost to air attacks while attempting to interdict the German evacuation from the Taman Bridgehead. As a result, Voroshilov did not participate in any further wartime operations.

After the war, Voroshilov underwent regular maintenance. In 1954, she began a post-war retrofit, but in 1955, the Soviet Navy determined that the planned upgrades were insufficient to modernize her as a combat ship. Instead, she was selected for conversion into a testbed for missile development and was redesignated as Project 33 in 1956. The conversion process was extensive, involving the removal of her armament and the installation of a new superstructure and masts. She was recommissioned as OS-24 in 1962 and further modernized between 1963 and 1965, earning the new designation Project 33M.

In 1972, Voroshilov was converted into a floating barracks and redesignated as PKZ-19. She was ultimately decommissioned and sold for scrap in 1973.

You can also find the remains of the Voroshilov’s Propeller and Stop Anchor at the Museum of Heroic Defense and Liberation of Sevastopol.

Maxim Gorky

Completed and commissioned into the Baltic Fleet in December 1940, she saw no action until 1941, when she provided cover for Soviet troops. This role resulted in damage that required repairs in Kronstadt. After her hull was fixed, she became immobile and remained in Kronstadt for the rest of the war due to the Axis minefield blockade. Despite being trapped, she contributed to the war effort by providing gunfire support during the Siege of Leningrad and Operation January Thunder.

Throughout the war, she underwent constant upgrades. In 1943, her deck armor was reinforced with an additional 37mm, and in 1944, all nine of her 45mm anti-aircraft guns were replaced with fifteen 37mm autocannons.

After the war, she remained with the Baltic Fleet. In 1950, she was tested as a landing platform for the first Soviet naval helicopter, the Ka-10. In 1953, she was moved to Kronstadt for a planned retrofit that was to include a complete overhaul of her machinery, the addition of torpedo bulges, and upgrades to her radar, fire-control systems, and anti-aircraft weaponry with the latest Soviet technology. However, the retrofit was ultimately canceled, and by 1955, the Soviet Navy deemed her unsuitable for modernization as a combat vessel.

Although she was considered for conversion into a missile testbed, Voroshilov was chosen instead. Decommissioned in 1956, she was scrapped in 1959.

Molotov

Completed and commissioned in June 1941, Molotov was initially stationed at Sevastopol, where she provided early air warning thanks to her radar during the early stages of Operation Barbarossa. In October, as German troops advanced into Crimea, she was transferred to Tuapse, bombarding German positions near Feodosiya en route. During December 1941 and January 1942, Molotov supported the evacuation and reinforcement of Soviet troops in and out of Sevastopol.

In March 1942, she provided fire support during the Siege of Sevastopol but sustained damage from German artillery and a heavy storm, requiring repairs in Poti. Between June and July, she transported Soviet troops to Sevastopol and evacuated refugees back to Poti. In August, after bombarding Feodosiya, Molotov was struck by a German torpedo bomber, creating a 20-meter-wide hole in her stern. Despite the severe damage, she managed to return to Poti for repairs, which lasted until mid-1943.

Following her repairs, Molotov did not participate in any further combat operations, as Stalin had prohibited the use of large naval units without his explicit permission. After the war, she served as a testbed for new air radars in the late 1940s. From 1952 to 1955, she underwent an extensive retrofit, which included the installation of modern air radars, sonar, and fire-control systems. Her light anti-aircraft guns were replaced with eleven twin 37mm autocannons, and her 100mm guns were upgraded to more modern versions.

Molotov participated in the rescue efforts after the sinking of Novorossiysk (formerly the Italian battleship Giulio Cesare). In August 1957, she was renamed Slava after Vyacheslav Molotov was purged from the government following an unsuccessful coup. Reclassified as a training cruiser in August 1961, she remained in service until being sold for scrap in April 1972.

Kalinin

Completed in late 1942 after significant logistical challenges in delivering her components from factories in European Russia to the Far East due to Operation Barbarossa, Kalinin was immediately commissioned into the Pacific Fleet as its flagship. In June 1943, orders were issued for her transfer to the Northern Fleet, but the move was canceled a month before her scheduled departure. As a result, she remained stationed in Vladivostok for the duration of the war.

After the war, Kalinin continued to serve in the Pacific Fleet, carrying out routine training and maintenance. She was decommissioned in 1956 but reactivated in 1957 before being converted into a floating barracks and redesignated as PKZ-21 in 1960. Ultimately, she was decommissioned again in 1963 and later scrapped.

Kaganovich

Although commissioned into the Pacific Fleet in 1944, Kaganovich was not fully completed until 1947 due to delays in the delivery of her components from factories in European Russia to the Far East. After the war, Kaganovich continued to serve in the Pacific Fleet, carrying out routine training. She was renamed as Lazar Kaganovich in 1945, and was again renamed Petropavlovsk in 1957 following Lazar Kaganovich’s purge from the government after an unsuccessful coup. Just a month after her renaming, she sustained damage from a typhoon.

In 1959, the Soviet Navy attempted to sell her to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), but the negotiations failed. Ultimately, she was converted into a floating barracks and sold for scrap in 1960.

Sources:

- Yakubov, V., & Worth, R. (2008). Raising the Red Banner: The pictorial history of Stalin’s fleet, 1920-1945. Spellmount.

- Chernyshev, Alexander & Kulagin, Konstantin (2007). Советские крейсера Великой Отечественной: от “Кирова” до “Кагановича”

- https://navsource.narod.ru/