This article examines the history of the MAA-1 Piranha, the first Brazilian domestic air-to-air missile, tracing its conception, development, testings, and the various setbacks and historical contexts that shaped the program. The Piranha was a bold project for its time, that sought to elevate Brazil into the small group of countries that were capable of producing domestic air-to-air missiles, a group which, at the time, consisted of France, the USA, the USSR, Israel, South Africa, the United Kingdom, China, Taiwan, and Japan.

Brazil’s first indigenous short-range air-to-air missile

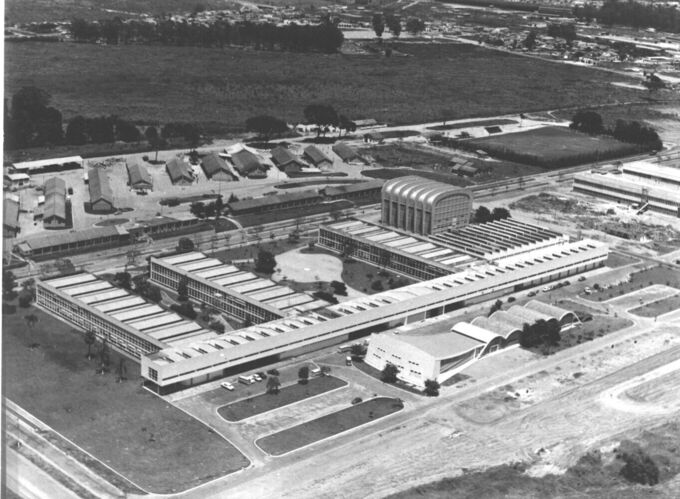

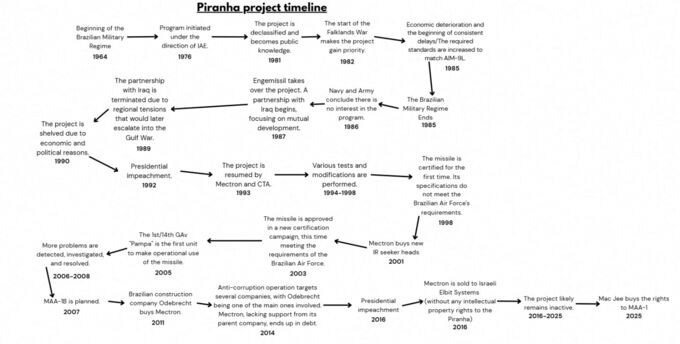

In the 1970s, Brazil was governed by a military regime and maintained a protectionist, relatively isolated economy. In this environment, nationalization became a central pillar of industrial policy, with particular emphasis on developing strategic technologies. As the country evaluated options to replace its aging stock of AIM-9B infrared (IR) missiles, policymakers faced a choice: continue depending on foreign suppliers or attempt a more ambitious, self-reliant path. Rather than pursuing another import, Brazil decided to turn to its own emerging industry in search of an independent solution. Development began in 1976 under the Institute of Aeronautics and Space (IAE), an institution subordinate to the Aerospace Technology Center (CTA). The project was led by Air Brigadier Hugo Piva, at the time director of the IAE. Overall coordination was provided by the General Staff of the Armed Forces (EMFA), which assigned engineers from all three military branches to support the effort.

In 1977, the control of the program was transferred to the Ministry of Aeronautics, which remained responsible for it until 1982, when control returned to EMFA. Throughout this early period, the CTA was the sole institution working on the missile’s development. The entire program was conducted in secrecy and was only officially released to the public in late 1981. At its inception, the Piranha was not intended to meet any urgent operational requirement; the Brazilian Air Force (FAB) viewed it primarily as a technological learning effort to prepare for more advanced future projects.

The situation changed abruptly in 1982 with the outbreak of the Falklands War. The conflict—and Argentina’s heavy dependence on imported military equipment—reinforced Brazil’s conviction that a self-sufficient defense industry was strategically essential. The project’s first development phase aimed to produce a missile with performance comparable to the AIM-9B, a milestone reached by 1978. The second phase sought AIM-9G-level capabilities, which was quickly achieved by the early 1980s.

To sustain progress despite growing financial difficulties, the program established a partnership in 1982 with D.F. Vasconcellos (DFV), a company experienced in military optics, including binoculars, rangefinders, night-vision devices, and armored vehicles sights. DFV became responsible for the missile’s seeker head and, in 1985, conducted five test firings at IMBEL’s facilities in Piquete, São Paulo. IMBEL was responsible for the missile’s solid fuel.

By late 1985, however, the program began experiencing significant delays. DFV, similarly to the general national industrial park, had entered a deep financial crisis. The military regime was nearing its end, the national economy was collapsing, and these conditions directly affected the companies involved in the project. Making the situation worse, the FAB reassessed the Piranha’s requirements after analyzing combat data from the Falklands War and the performance of the AIM-9L. The Air Force concluded that AIM-9G-class capabilities would be inadequate for future needs, and as a result, project specifications were raised to target AIM-9L-level performance, especially its all-aspect lock-on capability.

During this time, DFV was bought by the multinational company Pilkington in 1986, which led to its removal from the program that same year.

Image Source: FAB IAE, Galeria de Ex-Diretores

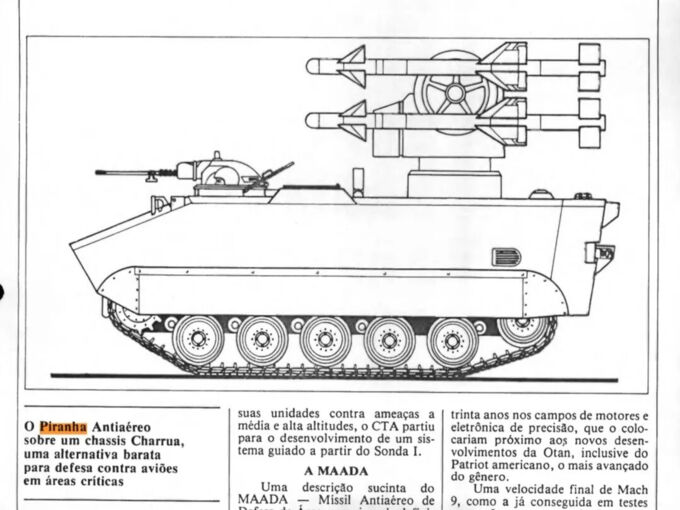

During this same period in 1986, the EMFA evaluated, together with the Navy and the Army, the possibility of the forces also using the missile that was being built. For the Navy, the missile would be mounted on corvettes and frigates, and for the Army, the creation of a mobile system using the Charrua amphibious vehicle, which would be similar to the US Chaparral. Both forces judged that it would not be necessary and preferred to continue focusing resources on their own projects like the Army’s Roland.

Source: Arquivo Nacional do Brasil, Fundo do EMFA: br_dfanbsb_2m_0_0_0231_v_05…

Further economic deterioration in 1987 forced the reallocation of program funds, and responsibility for the missile was transferred to Embraer and Engesa (Engesa would go bankrupt five years later). Together, the two companies created Engemíssil, later on called Órbita Sistemas Aeroespaciais, which also included participation from IMBEL, Parcon, and Esca (Esca would close seven years later). The company was short-lived, and would be shut alongside Engesa.

In an effort to keep the program alive despite these setbacks, Brazil entered a short-lived partnership with Iraq (It’s worth mentioning that Brazil already had a good number of prior experiences with Iraq, at the time operating a range of Brazilian equipment such as the Urutu and Cascavel armored vehicles, the ASTROS artillery system, and the A-27 Tucano) in 1987, aiming to reduce costs and pursue joint development. The collaboration was suspended in 1989 and, two years later, in 1991, the Iraqi government officially terminated the project, as regional tensions escalated in the lead-up to the invasion of Kuwait and the Gulf War.

Political instability soon compounded the project’s difficulties. In 1990, Brazil inaugurated its first democratically elected president since the end of the military regime. President Fernando Collor sought to curb the country’s 1,600% hyperinflation and ease international pressure stemming from sanctions and economic isolation. As part of his administration’s cost-cutting measures, numerous military programs were canceled or shelved, from the nuclear weapons program to the Piranha project, which had only not been officially cancelled at this point due to the persistence of the Ministry of Aeronautics. The CTA continued to work on its own, at a snail’s pace and with extremely limited funding available to it. Collor himself would be impeached just two years later.

By late 1993, the national situation had begun to stabilize under President Itamar Franco, whose administration achieved modest economic improvements. With conditions improving, the FAB judged the moment suitable to resume its independent missile program. Development was revived at full strength by Mectron (After the project in Iraq ended, several of the remaining engineers and scientists returned to Brazil, where they regrouped; some of them would later go on to found Mectron.) in partnership with the CTA.

Because of the accumulated delays, Brazil tried to purchase AIM-9L missiles from the United States as an interim solution. The request was denied; Washington offered only older variants, such as the AIM-9H, which the FAB promptly rejected.

When Mectron assumed control of the project, the remaining work was expected to be a straightforward final phase focused on certification and testing. The supposedly simple task, however, quickly proved arduous. Subsystems that had performed well in the laboratory had never been subjected to real-world stresses such as vibration, g-forces, or extreme temperatures. Once full testing began in late 1994, serious issues emerged; in one case, the seeker head nearly disintegrated during vibration trials. This forced Mectron to redesign much of the missile’s internals.

Between 1994 and 1997, more than 30 test launches were conducted, gradually moving past the program’s technical hurdles. The primary testbed throughout the campaign was the AT-26 Xavante, the Brazilian-built, Embraer-produced version of the Aermacchi MB-326. The missile was certified in 1998, but still failed to meet certain Air Force requirements, most notably all-aspect lock-on capability. (That same year, Brazil acquired the Python 3 as a temporary stopgap.)

In 2001, the Ministry of Defence formally warned Mectron that the contract could be terminated if the requirements were not met.

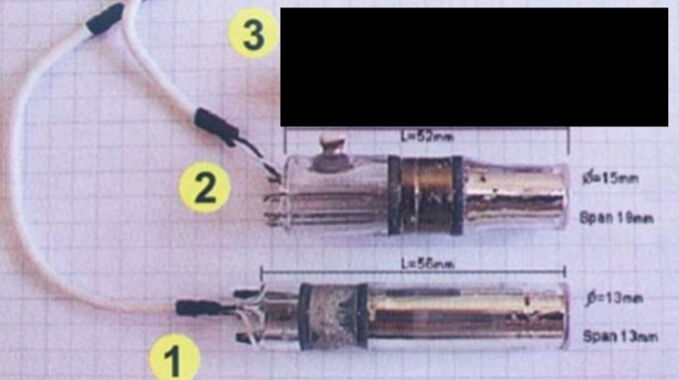

Mectron reacted quickly. Instead of developing a new IR detector entirely from scratch, the company purchased seeker units from a U.S. supplier. When they arrived, engineers discovered that the detectors were shorter and thicker than the previous model, forcing a complete redesign of the seeker head. The effort proved futile: testing revealed that the new detectors were inferior in quality. The setback cost Mectron roughly half a million dollars.

The company moved on and acquired new IR detectors—this time from South Africa’s Kentron—which were fully functional and served as the basis for an improved national seeker. By 2002, Mectron had developed a seeker capable of distinguishing flares and, when required, integrating with a head-mounted display (HMD). This progress triggered another certification campaign, including tests on the F-5E’s wingtip pylons, where vibration interference momentarily blinded the seeker for a few hundredths of a second after launch, increasing the risk of failures. Once these issues were resolved, the missile certified in 2002 was significantly more robust and reliable than the 1998 version.

The MAA-1 underwent another round of certifications in 2003, during which it was found to exceed all FAB requirements; it was officially declared operational in May 2005. The first unit to field the missile was the 1st Squadron of the 14th Aviation Group (1º/14º GAv) “Pampa.”

Certified, but Not Trouble-Free…

With the end of theoretical testing and the beginning of operational use, however, the Piranha continued to reveal certain issues. In 2005, the Brazilian Air Force contracted Denel Systems (formerly Kentron) to evaluate in 2006 the missile against Skua drones towing an IR source. In these trials, the missile consistently detected the target too late and with difficulty, achieving a hit rate of just 11% (1/9). The root of the problem lay in the testing conditions: during the 2003 F-5E certification campaign, the target had been a suspended flare with much higher IR emission than the Skua. Against the drone, mechanical vibrations introduced energy noise into the seeker, effectively overwriting the missile’s control signals.

The missile was subsequently reworked, and in new trials conducted in 2007, performance improved dramatically, achieving a success rate of over 70% (5/7, including three direct impacts).

Another issue emerged when missiles detached from aircraft during landing. The cause was traced to the launcher rack. When the program began in the 1970s, Brazil operated only the AIM-9B, which served as the basis for the MAA-1; its racks used aluminum attachment points, a feature carried over into the Piranha’s design. These aluminum lugs were prone to bending or failing under certain conditions. Around the same time, Brazil had acquired the AF-1 Skyhawk (A-4KU and TA-4KU Skyhawk II) from Kuwait, which arrived with AIM-9H missiles. Upon examining these missiles, Mectron noted that they used steel attachment points. The launchers were promptly updated to use steel as well, resolving the issue.

The MAA-1 is currently operated by Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Pakistan and possibly Indonesia. It is used on aircrafts such as the: AMX A-1A and A-1M, possibly the Brazilian Navy AF-1 Skyhawk, A-29 Super Tucano A and B, AT-26 Xavante (testbed) and F-5E/F, EM/FM BR. It stands out as the only missile in the world, besides the Sidewinder itself, capable of being deployed on the wingtip pylons of the F-5 without any additional preparation or restrictions. This is the result of intensive work by the CTA with Embraer, as Northrop refused to hand over the results of the F-5 flutter tests.

The 1998 variant was certified for use on the F-103E, but the aircraft was retired in 2005, the same year the “final” missile variant entered service, meaning it never actually carried the weapon operationally. It is unlikely that the Mirages 2000B/C used by Brazil from 2006 to 2013 ever used the MAA-1, considering that the jets were acquired solely as a temporary measure and were already using the Matra R550 Magic 2.

Source: Author

Source: FAB www.fab.mil.br

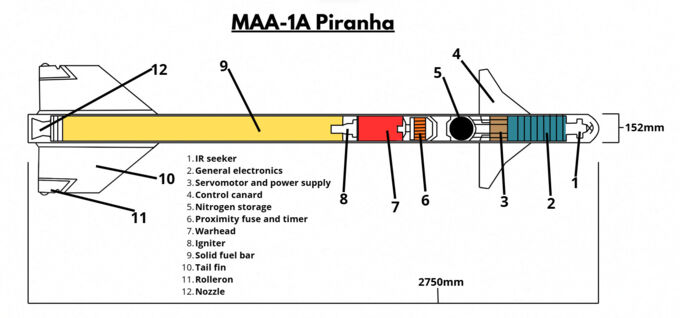

- MAA-1A data:

Weight: 89 kg;

Lenght: 2750 mm;

Diameter: 152 mm;

Wingspan: 600 mm;

Speed: Mach 3.5, 4000+ km/h;

Fuel type: Solid fuel;

Combustion time: 2.1 s;

Operating temperature: — 40ºC ~ + 50ºC;

Maneuverability: 45 G;

Mission time: 40 s;

(Specifics may somewhat vary, depending on the source)

The future of the MAA-1 project

A major political crisis struck Brazil in the mid-2010s due to large-scale corruption scandals—culminating in the impeachment of yet another president in 2016. Within this context, Mectron, responsible for the modernization and development of the MAA-1, fell into a severe financial crisis starting in 2014. Odebrecht, the construction conglomerate that controlled the company, came under federal intervention, which cut off the financial ropes that had been holding up Mectron’s operations.

As a result, Mectron was acquired in 2016 by the Israeli company Elbit Systems. However, Elbit did not obtain the intellectual property rights to the missile family. These rights were eventually purchased in November 2025 by the Brazilian defense company Mac Jee.

This succession of setbacks throughout the 2000s and 2010s resulted in substantial delays to the program. The current status of the MAA-1B (likely dormant for the past seven years) remains uncertain. What is known is that the project appears to remain under development and is intended to evolve into a true fourth-generation short-range air-to-air missile, with performance comparable to the R-73 and Python-4. Planned characteristics include 60-G maneuverability, an extended effective range enabled by a new propulsion system, and a more advanced IR seeker.

You can find images of the MAA-1B mockup online.

Additional note:

When Mectron was acquired, most of its engineers and scientists were laid off. In the weeks that followed, several of these professionals regrouped and founded SIATT, a company that would later take responsibility for programs such as MANSUP, MANSUP-ER, and MAX 1.2, among other technologies. This same technical group (previously involved in the creation of Mectron after the end of the Iraqi partnership) went on to establish another firm that remains a relevant developer of missiles and defense technologies.

Source: Author

In-game usage

The MAA-1 is a missile with excellent maneuverability and decent range. Its major flaw is how easily it is distracted by countermeasures, lacking the jamming resistance generally attributed to it in real life, a fact acknowledged in the video “AMX A-1: The Brazilian Piranha” from the official series The Shooting Range, episode 420: “They could use some jamming resistance, but that’s a feature reserved for higher battle ratings.” As a result, firing at targets that have countermeasures and are either aware of your presence or preemptively dispensing flares should be avoided. You should instead focus on defenseless (flareless), preoccupied or oblivious opponents, who will simply fly in a straight line or go for their base without a care in their world. Its effective range is just over 2.5 km, assuming you are gaining on your enemy.

As the launch platform of the MAA-1, the AMX A-1A, is a subsonic aircraft, your best opportunities to launch the Piranhas will be against already dogfighting enemies tied up with your allies, or people you managed to sneak behind/above/below who may not be aware of your presence. It is generally recommended to avoid launching both of your missiles at the same target, as if they manage to flare one missile there’s a good chance they’re aware enough to flare your second missile as well.

The AMX A-1A is currently the only aircraft in the game capable of operating these missiles.

Sources:

- Site Sistema De Armas

- Opto Eletrônica

- Pesquisa FAPESP 'Innovation in defense'

- Revista Sociedade Militar

- AEROIN

- DEFESANET (1)

- DEFESANET (2)

- Defesa Aérea & Naval

- Deagel

- ECSBDefesa

- Brigadeiro Engenheiro Venâncio Alvarenga Gomes em palestra. 62° FPB

- Freepages/RootsWeb — archival mirror of a defunct early-2000s Piranha program page

- cmano-db

- loneflyer

- Fox 3 Kill Podcast, episodio 35, Carlos Alberto, Diretor de Competitividade da SIATT

- Iqbal, Saghir (2018). JF-17 Thunder: The Making of a Modern Cost-effective Multi-role Combat Aircraft. Saghir Iqbal. p. 106. ISBN 9781984055248.

- webarchive mectron ficha técnica maa-1

Extra and reading: