In the early Cold War era, the Belgian Air Force (Force Aérienne Belge, FAB) faced the challenge of modernizing its fighter fleet to meet escalating NATO air defence demands. During the 1950s, Belgium operated subsonic fighters such as the Republic F-84F Thunderstreak and the Hunter F.6, which were increasingly seen as inadequate against emerging high-speed threats. In response, NATO initiated a coordinated effort to equip several of its European members with a supersonic multi-role platform capable of both interception and tactical strike duties. Belgium opted to join this programme by selecting the Lockheed F-104G Starfighter, a derivative of the original Lockheed F-104 designed with enhancements tailored for European operations.

The F-104G represented a significant technological leap for the Belgian Air Force: it was a Mach 2-capable aircraft with advanced avionics, steep climb performance, and adaptability for air defence and strike roles. Its introduction marked the culmination of transition from early jet fighters to a modern supersonic capability for NATO’s northern flank.

Design and Specifications

The F-104G’s design prioritized high-speed performance and operational flexibility. It was powered by a single General Electric J79-GE-11A turbojet engine, which enabled speeds exceeding Mach 2 at altitude and a climb rate among the fastest of its generation. The aircraft’s avionics suite (as of its most modern upgrade) included an Autonetics NASARR F15A-41B radar system for air-to-air interception and basic ground mapping capability, as well as a Litton LN-3 inertial navigation system which improved long-range navigation and weapons delivery.

Armament consisted of the M61A1 Vulcan 20mm rotary cannon, typically mounted internally, and provisions for AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles, bombs, and rockets on underwing and fuselage hardpoints. Belgian Starfighters were also configured to carry tactical nuclear weapons in support of NATO doctrines at the height of the Cold War.

Belgian F-104Gs initially appeared in natural metal finish but subsequently transitioned to a Vietnam-era camouflage scheme featuring two-tone green and tan upper surfaces with light undersides as part of mid-life refurbishment programmes in the late 1960s.

Performance highlights included a service ceiling over 15,000 m and the ability to accelerate rapidly to high altitudes, making it well suited to interception roles. One F-104G (serial FX-11) notably set a Brussels-Paris speed record of 9 min and 55 sec in 1963 with an average speed exceeding 1,576 km/h.

Development and Acquisition

The F-104G variant was developed under a consortium led by Lockheed but built under licence in several European countries, including Belgium. The Belgian government initially placed its order in 1960, committing to 100 F-104G single-seat fighters and 12 TF-104G two-seat variants. Of these, 25 single-seat aircraft and three two-seat trainers were funded under the U.S. Military Assistance Program (MAP), which was typical at the time for BAF acquisitions.

Domestic aerospace participation was a key feature of the procurement: SABCA (Société Anonyme Belge de Constructions Aéronautiques) assembled the majority of the F-104Gs in Belgium, while Fabrique Nationale (FN) manufactured 1,225 General Electric J79 turbojet engines under licence, which were used not only by Belgium but also supplied to other F-104 operators in Europe.

The first Belgian Starfighters began arriving in February 1963; the type officially entered service with the Belgian Air Force later that year. One aircraft originally assigned the serial FX-27 crashed before delivery and was replaced by a new airframe bearing the same serial number.

Operational History

Entry Into Service

The F-104G arrived in Belgium during a period of evolving NATO strategy. The first formal deliveries were made in April 1963 when aircraft such as FX-03 and FX-04 were presented in public ceremonies.

The Belgian Starfighter completed pilot conversion and early operational evaluation with support from training units in West Germany who already had this type in service. Belgian pilots transitioned onto two-seat trainers and dual-control platforms before returning to Belgium for frontline duties.

NATO Integration and Missions

Belgium’s Starfighters stood alert in support of NATO’s integrated air defence network throughout the Cold War. At Beauvechain Air Base, F-104Gs maintained quick-reaction alerts ready to intercept intruding aircraft across the Western European theatre, often operating in conjunction with neighbouring NATO air forces. At Kleine-Brogel Air Base, F-104Gs conducted tactical strike training, low-level navigation exercises, and weapons delivery profiles including conventional and nuclear strike scenarios.

Belgian F-104s participated in regular NATO deployments and multinational exercises across Germany, Italy, and France, often flying intensive sortie schedules that tested both pilot endurance and the aircraft’s systems.

Tactical Evaluations and Upgrades

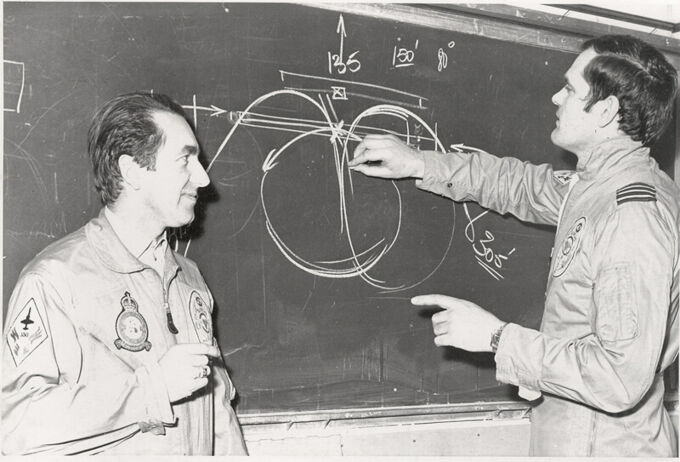

During its operational life, the Starfighter fleet underwent upgrades in avionics, navigation, and weapons delivery systems to maintain relevance. Most of the equipment noted in Design was absent at first. Early modifications focused on avionics and navigation, including the NASARR (North American Search and Range Radar) system, which integrated low- and high-altitude navigation and basic fire-control functions. The crews trained extensively on two converted DC-3 “Pinocchio” aircraft equipped with NASARR, allowing pilots to master the new avionics without the complexities of the F-104G itself.

Mid-life upgrades expanded or ensured operational capabilities, but were universal across most non-SABCA F-104Gs too, as SABCA supplied the integration of the NASARR. These included the installation of earlier discussed improved radar and navigation packages (like the Litton LN-3 inertial navigation system), mostly by updating the software or replacing hardware with more modern or durable components in the radar systems, allowing for more precise interception missions at both high and low altitude. Experimentation with Sidewinder missile rails on the fuselage was briefly conducted in 1970, as they weren’t available before that on the SABCA models, but they didn’t remain in-service for long with these, as the F-16 took over this role in the 1980s. All of these upgrades were typical for the F-104G in German and Dutch service as well: Specifically structural reinforcements for low-level penetration and ground-attack operations were immediately retained from the German F-104G specifications and plans, and with help from SABCA and Fokker, implemented on Dutch F-104G as well.

One specific feature which let the Belgian F-104G stand out among its class were the large amount of liveries used during NATO missions and training exercises, but in other parts it was mostly near-similar and identical in capabilities in Dutch, Italian and German F-104G single-seat models.

Squadrons and Units

Belgian F-104Gs were assigned to four frontline squadrons within two wings:

| Wing | Air Base | Squadron | Role | Period of F-104G Operation | Squadron Emblem / Nickname | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Fighter Wing | Beauvechain AB | 349 Squadron | All-Weather Interceptor (AWX) | Nov 1963 — Mar 1980 | Nailed balls on chain | Primary NATO QRA and interception unit; first Belgian squadron to operate the F-104G operationally |

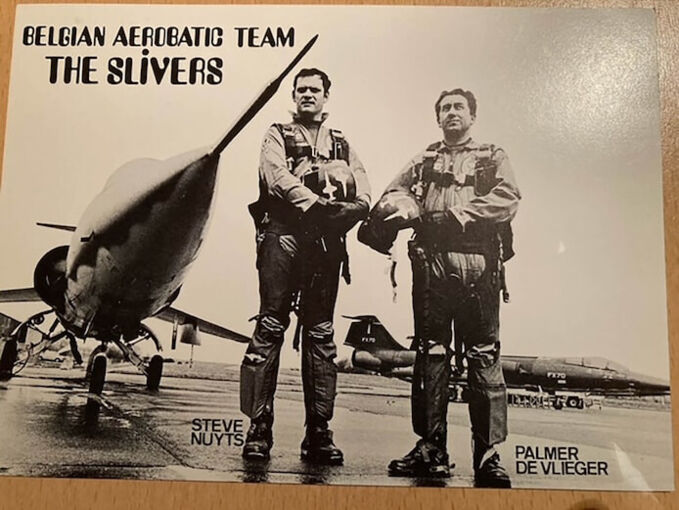

| 1st Fighter Wing | Beauvechain AB | 350 Squadron | All-Weather Interceptor (AWX) | Mar 1963 — Oct 1981 | Viking head | Home squadron of the Slivers aerobatic team; extensive NATO exercise participation |

| 10th Tactical Wing | Kleine-Brogel AB | 23 Squadron | Fighter-Bomber (FB) | Apr 1964 — Dec 1982 | Red Devil | Specialized in low-level strike and tactical weapons delivery |

| 10th Tactical Wing | Kleine-Brogel AB | 31 Squadron | Fighter-Bomber (FB) | Jun 1963 — Oct 1983 | Tiger | Last Belgian squadron to operate the F-104G; flew the final operational Starfighter sortie |

| Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) | Beauvechain AB | Training / Conversion | 1963 — 1979 | Responsible for pilot transition to the F-104; initial training conducted in West Germany (Nörvenich, Jever) |

Each squadron adopted unique tail markings and traditions, including wing-specific symbols and heritage identifiers, that reflected the Belgian Air Force’s culture (from the air service in WWI) and tactical roles (ex.g. The Red devil specialising in FB configurations, and the nailed ball on chain (Flail), being a mostly interceptor figter-vs-fighter squadron).

Aerobatic and Display Operations

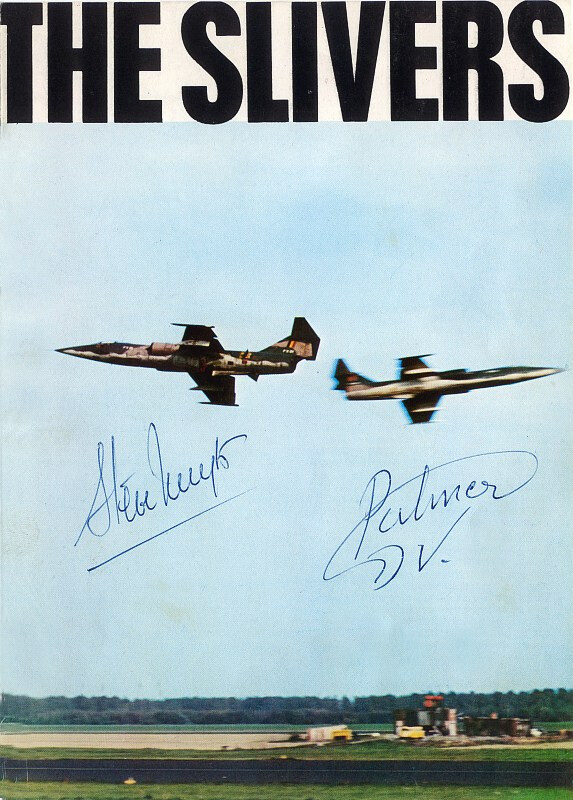

Belgium distinguished itself among NATO operators by fielding a dedicated Starfighter demonstration team known as “The Slivers.” Active from 1969 to 1975, the team performed fast, precision passes and synchronized manoeuvres in high-speed, low-level flight profiles that demonstrated both pilot skill and the performance envelope of the F-104G. Despite the aircraft’s high landing and stall speeds, the Slivers completed all official performances without accident, earning recognition across Europe for their tight formations and daring profiles.

Aerobatic Team — The Slivers

The team’s name derived from the nickname “Silver Sliver”, a term used by Lockheed test pilots to describe the F-104’s slender fuselage and extremely short wings. While most air forces restricted the Starfighter to strictly operational flying due to its high landing speed and limited turning capability, the Belgian Air Force demonstrated exceptional confidence in its pilots by authorizing public displays with the type.

Formation and Background

The creation of the Slivers followed a temporary prohibition on Belgian F-104 demonstrations after a fatal accident in September 1968, when Captain François “Susse” Jacobs was killed during a filming flight for the television series Les Chevaliers du Ciel. The ban was later lifted thanks largely to the efforts of Colonel Paul De Wulf, commanding officer of Beauvechain Air Base, who argued that carefully planned displays could be conducted safely and professionally.

The team was officially formed in 1969 at Beauvechain, home of the 1st Fighter Wing and its interceptor squadrons. Initial concepts envisioned pilots from both 349 and 350 Squadrons, but training limitations led to the selection of two pilots from 350 Squadron instead. Their first public performance took place on 14 May 1969 during a graduation ceremony at Brustem Air Base, marking the debut of the world’s first F-104 aerobatic duo.

Pilots

Unlike larger national display teams, the Slivers consisted of only two aircraft, emphasizing precision and symmetry rather than complex formations. The team was supported by a single dedicated crew chief, ensuring consistency in aircraft preparation and maintenance.

Aircraft and Appearance

The Slivers flew standard Belgian F-104G Starfighters in the contemporary Vietnam-style camouflage scheme, consisting of green and tan upper surfaces with light grey undersides. No dedicated airframes were permanently assigned; instead, multiple aircraft were rotated through the team over the years, with favored examples including FX-90, FX-72, FX-68, FX-51, and FX-52.

The aircraft retained their AIM-9 Sidewinder launch rails, which contributed to directional stability during high-speed passes. For visual identification, the rails were painted white or red and carried the word “SLIVERS” in contrasting lettering. From 1971 onwards, the team name also appeared on the engine intakes, replacing an earlier and short-lived experiment with red-painted intake lips.

Display Profile and Performances

Slivers displays were characterized by high-speed, low-altitude passes rather than traditional looping aerobatics. Typical display speeds were around 400 kn indicated airspeed, with peak passes exceeding 700 km/h. The team performed synchronized runs with lateral separation of as little as 2 to 10 m, often aligning one aircraft over the runway surface and the other over adjacent grass to create the illusion of extreme proximity.

Despite the F-104’s limited turning performance and high wing loading, the Slivers developed a display routine that emphasized precision timing, minimal control inputs, and strict adherence to safety margins. Over seven seasons, the team conducted more than 70 official displays across Belgium, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy, all without incident.

Disbandment and Legacy

The Slivers were disbanded in July 1975, following Major Nuyts’ promotion and the absence of a suitable replacement lead pilot. By this time, the Belgian Air Force was already preparing for the transition from the F-104 to the F-16, and resources were increasingly focused on operational conversion.

Today, the Slivers are remembered as pioneers of F-104 demonstration flying. Their flawless safety record and disciplined approach challenged the aircraft’s reputation and highlighted the skill of Belgian Starfighter pilots. Artifacts, photographs, and memorabilia from the team are preserved at Beauvechain Air Base Museum, ensuring that their contribution to Belgian and NATO aviation history remains recognized.

Accidents and Safety Record

Operating advanced supersonic aircraft in demanding environments carried inherent risks. Over the Belgian F-104G’s 20-year service life, the fleet suffered 41 aircraft losses (38 single-seat F-104G and 3 two-seat TF-104G), equating to approximately 37% of the total force. These losses resulted from a mix of technical failures, mid-air collisions, controlled flight into terrain during low-level training, and other operational hazards that were emblematic of the era’s high-performance jet operations.

Very few resulted in deaths of casualities, but one became rather famous at the time:

The Crash at Gosselies Airport (18 August 1964)

On Tuesday, 18 August 1964, a Belgian Air Force Lockheed F-104G Starfighter, serial FX-66, was destroyed in a fatal accident at Gosselies Airport, in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. The crash occurred at approximately 14:07 local time during a low-level aerobatic training flight.

While performing manoeuvres at low altitude, the aircraft lost control and struck a hangar on the airfield. The impact resulted in the total destruction of the Starfighter and caused significant damage to aircraft stored inside the hangar. The pilot, Captain Aviator Pierre Tonet, was the sole occupant of the aircraft and was killed in the accident.

In addition to FX-66, several civilian aircraft parked in the hangar were destroyed by the crash and ensuing fire, including:

- OO-JOD — Jodel D150 Mascaret

- OO-JOY — Jodel DR1051M1 Sicile Record

- OO-FER — Piper L-18C Super Cub (ex-USAF 53-4687, L-13)

The accident occurred during a period when the Belgian Air Force was still gaining operational experience with the F-104G, particularly in demanding low-altitude flight regimes. Although the exact technical cause of the crash was not publicly detailed, the incident highlighted the inherent risks associated with low-level aerobatics in high-performance supersonic aircraft such as the Starfighter.

The crash of FX-66 was one of the early fatal losses in Belgian F-104 operations and contributed to ongoing evaluations of flight safety procedures and display restrictions within the Belgian Air Force during the mid-1960s.

Retirement and Legacy

By the late 1970s, the next generation of fighter technology was arriving. Belgium elected to modernize its air force with the General Dynamics F-16A/B Fighting Falcon, a multi-role platform with advanced avionics and fly-by-wire controls. Transition to F-16s began with the 1st Wing, followed by units at Kleine-Brogel.

The final Belgian F-104G left service on 19 September 1983, marking the end of a remarkable chapter in Belgian aviation history. Following retirement, surviving aircraft were distributed to foreign users and museums: 18 and 23 aircraft were transferred abroad (principally to Turkey and Taiwan), while others were scrapped or preserved as static displays and training airframes.

Today, preserved Belgian Starfighters remain on display in museums and air bases across Europe, serving as reminders of both the aircraft’s capabilities and the bravery of the pilots who flew them.

- Aerobatic Teams. (n.d.). Slivers demonstration duo. https://aerobaticteams.net/en/teams/i163/Slivers.html

- Aerobatic Belgium Air Force RBAF Squadron Slivers Demonstration. (n.d.). eBay. https://www.ebay.com/itm/312549667424

- Appeal for pics of the Belgian Slivers F-104 display duo. (2023, July 21). Fighter Control. https://www.fightercontrol.co.uk/forum/viewtopic.php?t=234664

- Belgian Air Force F-104G display team. (2025, December 13). [Facebook post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/107143362640745/posts/25582816701313394/

- Belgian TF-104G and F-104G Starfighter at Beauvechain AB (1968). (2019, September 17). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLEhp0iSK3g

- Best of Flightgear. (2006, August 22). The Slivers. http://www.best-of-flightgear.dk/slivers.htm

- F-104 service history. (n.d.). 916 Starfighter. https://www.916-starfighter.de/F-104_ServiceHistory.htm

- F-104 Starfighter aircraft history and reputation. (2024, August 29). [Facebook post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/122160938171362/posts/2547731075614324/

- F-104G FX52, 350 Squadron Sliver display team, 1st Fighter Wing, Belgian Air Force. (2024, February 4). [Facebook post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/100070305451296/posts/f-104g-fx52-350-squadron-sliver-display-team-1-fw-belgian-air-force-at-raf-upper/445374614482717/

- F-104G Starfighter period. (n.d.). Kleine-Brogel Air Force Museum. https://kbam.be/e_vliegveld5.php

- International F-104 Society. (n.d.). Squadrons — Belgian Air Force. https://www.i-f-s.nl/squadrons-belgium-air-force/

- International F-104 Society. (2022, July 11). The Slivers. https://www.i-f-s.nl/story/the-slivers/

- Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_F-104_Starfighter

- Lockheed F-104 Starfighter operators: Belgium. (n.d.). Vietnam Warbirds Resource Group. https://vietnam.warbirdsresourcegroup.org/f104starfighter-operators.html

- Lockheed F-104G Starfighter. (n.d.). Planes of Fame Air Museum. https://planesoffame.org/aircraft/plane-F-104G

- Lockheed F-104G Starfighter (Part 1). (n.d.). Belgian Wings. https://www.belgian-wings.be/lockheed-f-104g-starfighter-1

- Ongena’s F-104 Starfighter touch-roll-touch manoeuvre. (2021, June 10). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sahaGnwqRX0

- Looby, P. (n.d.). F-104G FX-47. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/ths7jP

- Erwin. (n.d.). Lockheed F-104G Starfighter c/n 683D-9164 Belgium Air Force serial FX94. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/Zj1BjY

- Hits, E. B.-. T. F. 2. M. (n.d.). Belgian AF — F-104G — FX-83 [5.81]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/23zN5Nm

- Lempereur, V. (n.d.). Lockheed F 104 G Starfighter FX 60 BAF — Flugausstellung — Musée aviation allemagne — 2016-09-14 13-22-15_327 mod et ret. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/SWUKSx

- Grant, L. (n.d.). FX90 Alconbury 28-6-1975. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/2mdRKnH

- File: Lockheed (SABCA) F-104G Starfighter, Belgium — Air Force AN2059463.jpg — Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lockheed_(SABCA)_F-104G_Starfighter, _Belgium_-_Air_Force_AN2059463.jpg