In 1939, a new style of warfare swept across Poland: Blitzkrieg. Utilising an extremely effective balance of speed, organisation and surprise to overcome entire nations, it was revolutionary compared to the slow, brutal First World War mindset of French and British tacticians. In this article, I will discuss how one aircraft, the Ju 87 'Stuka', was central to Blitzkrieg, and how it was perfectly engineered for terror bombing.

Blitzkrieg

In 1916, one of the worst massacres in the history of war took place on the battlefield of Verdun, where 300,000 men lost their lives, cut up by brutal artillery bombardments and machine gun fire as they repeatedly slogged forward to each other’s positions, unsuccessfully. British and French High Command, as the victors, mistakenly believed that it was such tactics that won them the war, and so modelled almost every aspect of their pre-WW2 strategies on the assumption that if a new war would take place, it would be in the trenches. Such a mindset is reflected in the designs of tanks such as the TOG II and the R.35, which had a 'skid' on its rear for crossing trenches. The French also adopted another style of warfare: defensive. This lead to the building of the Maginot line, a huge network of underground bunkers facing Germany, which would ultimately become one of France’s biggest failures during the German invasion. Clearly, Sun Tzu’s saying “Attack is the secret of defence” was lost on them.

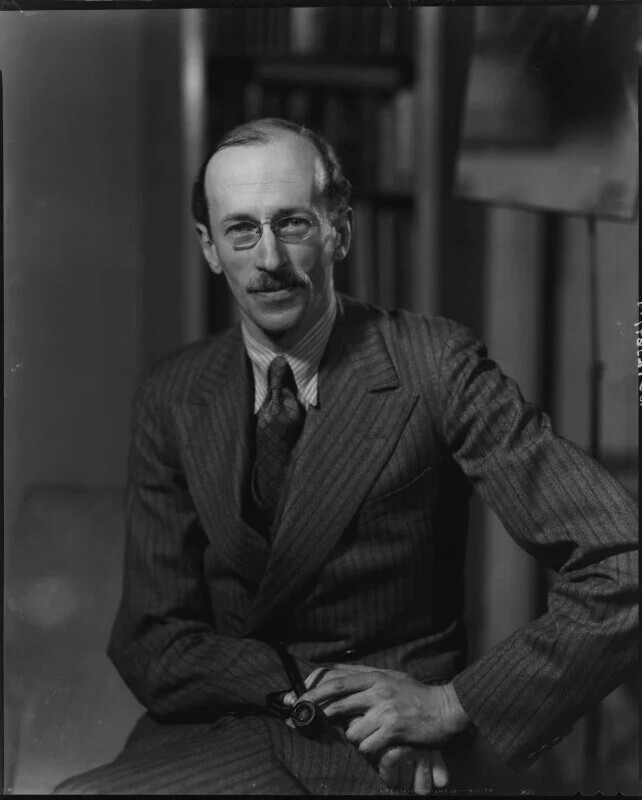

However, there were some strategists, such as Sir Basil Liddell Hart, who realised that it was in fact both cheaper and more effective if, rather than throwing hundreds of men, tanks and guns into a battle, an army disabled the enemy’s supply lines and communication, effectively breaking its back. In Germany, men such as Heinz Guderian and Erwin Rommel, both disciples of Liddell Hart, seized on the concept, naming it 'Blitzkrieg': 'Lightning War'.

But how would the Wehrmacht attack the enemy’s supply lines? No artillery would be able to accurately strike it, and so another solution had to be found: the 'Stuka' dive-bomber, designed in secret from the Allies who had placed restrictions on Germany’s air force. It is here that confusion is aroused by the name 'Blitzkrieg'. Some people suggest that the 'Blitz' element refers to the lightning-like speed with which such operations were conducted. In fact, according to Liddell Hart himself in Purnell’s History of the Second World War, this tactic’s name illustrates how, from a distance, the dive-bombing Stuka strikes on the enemy looked like sporadic bursts of lightning; flashing down, causing chaos, and then disappearing into the clouds.

Dive-bombing, the Blitzkrieg’s secret weapon

Essentially, without the Stuka, Blitzkrieg wouldn’t work, but without Blitzkrieg, the Stuka would never become well-known. Why was this?

First, dive bombing was a perfect solution to the question of how to accurately destroy enemy supply lines. This was not only because an artillery shell’s range was somewhat limited, but also because a lot of the firing was just ranging shots. In addition, it was difficult to follow the enemy’s movements with artillery fire, especially when the enemy was behind the lines. In contrast, the dive bombing meant that the explosive — in the Stuka’s case a bomb — could be guided with human intervention right until its point of impact, allowing for a level of accuracy not seen before. This also meant that the enemy was basically surrounded from all sides, as the marauding Stukas could strike as far behind the enemy’s lines as they liked.

The amount of Ju 87s in service in 1939 is surprising: only around 350, as oppose to around 790 He 111s at that same time. This actually shows the Stuka’s effectiveness; theoretically, at least. With medium bombers, like the He 111, where hitting a target was more luck than skill, mass formations of up to a hundred aircraft were needed to have a safe chance of striking a target, hence the large amount of bombers in service. In contrast, due to the high accuracy of dive-bombing, only one or two Stukas might be sent to destroy a target, putting fewer lives at risk.

Dive-bombing was also well-suited to CAS (Close Air Support) operations as well. Being in mobile aircraft with radio contact meant that, if the front line changed or another threat appeared, the dive-bombers could easily change their target through constant contact with the ground forces. This in fact is another reason Blitzkrieg was so effective: precise inter-unit communication and coordination meant that different branches of the Wehrmacht, such as the Luftwaffe and the Panzers, could constantly give each other the specific support needed, allowing them to maintain a constantly changing front-line.

The Stuka made a name for itself because dive bombers were hardly used outside of Germany and other nations hadn’t adopted Blitzkrieg tactics. Dive-bombing had no place in the defensive strategies of the British and French because it was solely an offensive weapon. This became clearer later in the war, when the Stuka faded into obscurity during purely defensive German actions such as the Normandy campaign.

The Stuka: perfectly engineered for dive bombing

But why was the Stuka used, instead of say, the Hs 123, as the main aircraft for Blitzkrieg? Well, the Ju 87 was a marvel of engineering for its time, including many dive-bombing features that gave it an edge over its peers:

- Inverted gull wing: This feature was included on the Stuka for one reason: aerodynamics, as Realistic Battles players will know all too well. With an aircraft with straight wings, such as the Hs 123, if diving or when reaching excessive speeds, the wings are prone to being torn off. Now, obviously, if something is forcefully pushed against an opposing force, it will break. Thus, by bending the wing, the wing root is strengthened, allowing for more force to be applied before the wing is torn off. Despite this benefit, bent wings were a relatively novel idea, not being used again until the development of the F4U Corsair. This is one of the reasons that the Stuka was so effective, as these wings allowed it to carry out extremely steep and fast dives with ease (up to 600 km/h), allowing for a greater degree of accuracy in bomb runs.

- 'Jericho Trumpets': These so-called 'trumpets' were in fact more like whistles with small wooden propellers on the front, attached to the fixed landing gear of the Stuka. When reaching around 190 km/h in a dive, these propellers would start to spin, channeling air flow into the whistles, thus creating a very loud screeching sound. This must have been absolutely terrifying to both soldiers and civilians, and was a new kind of psychological warfare. This suited the German tactic of terror bombing perfectly, creating bewilderment and chaos amongst the enemy — and refugees. The 'trumpets' were the suggestion of the First World War pilot Ernst Udet, who was apparently in love with the idea of the dive-bomber. Originally called 'Lärmgerät' by the German inventors, these whistles gained their better-known nickname during the siege of Malta, when terrified British soldiers compared the sound to that of the Biblical 'Trumpets of Jericho', which could knock down walls with their noise. In fact, they proved to be extremely annoying for the pilots who, taking matters into their own hands, kicked the whistles off their aircraft themselves! Therefore, they were only used on the B and R series of the Stuka.

- Airbrakes: These

were strips of metal, attached to the underside of the Stuka’s wings.

When deployed (usually just before entering a dive), the nose of the

aircraft is automatically tipped forward into a dive. In addition, they

slowed down the aircraft, allowing the pilot to maintain a steady speed

of 580 km/h, making it easier to control the aircraft in a dive.

- Automatic Dive Recovery System: Due to the extreme G-forces experienced when in a dive, pilots of dive bombers were prone to blacking out and the aircraft could crash, killing the pilot. Therefore, an ingenious system was introduced into the Ju 87, known (in English) as the Automatic Dive Recovery System. When the final bomb of the aircraft was dropped, an automatic electric signal was sent to the trim tabs on the tail, which would trigger a magnet, making it pull on the control column, therefore pulling the aircraft out of a dive automatically. One can only imagine the amount of lives this contraption saved!

Note: this feature is accurately modelled in Simulator Battles.

- Leather head-rest: As previously mentioned, it was common for a pilot to black out when entering a dive. The majority of cockpits during the Second World War were made of metal or Bakelite, for durability. Thus, there were lots of various sharp and hard edges, like the rim of the dashboard. If a pilot blacked out during a dive, he would probably slump forward; in doing this in the confined space of a cockpit, he would almost certainly hit his head, possibly causing concussion and serious injury to himself. So, a leather band filled with a soft material, like foam padding, was added just in front of the gun sight to prevent such accidents. Whilst this was by no means a new invention (being used on other aircraft like the Hs 123) it was certainly an important addition to the Stuka’s cockpit.

- Bomb release sound: Even though dive bombing allowed for a great deal of accuracy, there was still a margin for error, due to the fact that it was controlled by a human, who could make mistakes. In order to lessen the chance of failure, designers of the Ju 87 added yet another interesting feature for the pilot. When he had manoevered his aircraft into a diving position of around 70°, at 250 metres above the target, a small buzz would go off in the cockpit, signalling that this was the optimal altitude for bomb release. Through this mechanism, the pilot wouldn’t have to constantly be estimating the distance between him and the ground, allowing him to release his load and pull out of the dive a safe distance from the ground.

With all of these features considered, it is easy to see why the Ju 87 'Stuka' was popular with both its pilots and German High Command. Not only was it an aircraft that marginalised the chance of human error, perfected the art of dive bombing and created a new form of psychological warfare by the use of sound, it was also a reliable aircraft that kept its pilots safe from harm and accidents.

Final thoughts and Conclusion

This article does, however, leave some questions unanswered: why don’t modern armies use dive bombers, even though the Stuka showed itself to be such an effective weapon in 1940? Why didn’t later Allied air forces use dive bombers in large numbers in the European sector of 1944-1945, even though they were on the offensive, a style of war perfectly suited to dive bombing tactics? Despite other nations' unwillingness to use the dive bombers, why did Germany keep producing them throughout the war, from the biplane Hs 123, to the Ju 88 series, to the Fw 190 F-8, and finally with the jet-engined Ar 234? Clearly, their faith in these tactics was unshaken, even when they were the defenders. As for the answers to these questions, one can only speculate, but could be the cause for some interesting discussions.

In conclusion, the Ju 87 Stuka wasn’t just a light bomber; it was designed perfectly for dive bombing, making it the central reason for the Blitzkrieg’s success, which revolutionised warfare in Europe, and set the tone for the style of warfare still used today.

Note: the quote in the title is from Mark Twain.

- Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk, by Len Deighton

- Purnell’s History of the Second World War, Volume 1, No. 3

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junkers_Ju_87

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BIqKK9BBGF0