Kamikaze (神風 “divine wind”) was a military tactic used in the later stages of the Second World War, used by pilots of the Imperial Japanese Air Force and Naval Air Service. The tactic consisted of an aircraft loaded with explosives; the pilot would then attempt to deliberately ram the aircraft into enemy ships to inflict damage.

Background and Origin

The term "kamikaze" (神風, meaning “divine wind”) originates from the fierce typhoons that repelled the Mongol invasions of mainland Japan in 1274 and 1281.

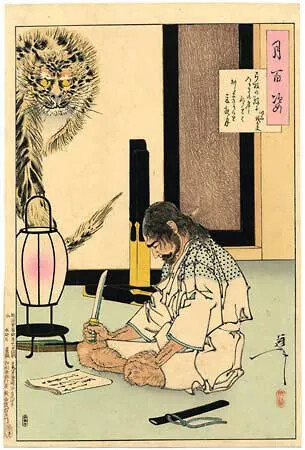

Samurai Code of Honor and Seppuku

Defeat and capture were seen as dishonorable and shameful in the military culture of this time. This can be attributed to one of the main values in the samurai code, or Bushido, which was to have loyalty and honor until death. This is why many Japanese pilots chose to crash into enemy targets and die instead of crash-land and accept capture and ultimate defeat, even before specific kamikaze units were formed in the military. Kamikaze is frequently compared to seppuku, which was ritual suicide committed by military members who were seeking to restore honor in their family by dying instead of accepting defeat (this was done by many Japanese leaders during and at the end of the war).

Kamikaze Missions in WW2

The Japanese leadership, realizing they needed a new tactic so they wouldn't lose the war, organized units especially for kamikaze pilots in early 1944. They were formally referred to as shinpū tokubetsu kōgeki tai (神風特別攻撃隊, "divine wind special attack units"). A commander named Asaichi Tamai asked a team of 23 young pilots if any of them wanted to join this "special attack force."

All of them raised their hands.

First Mission

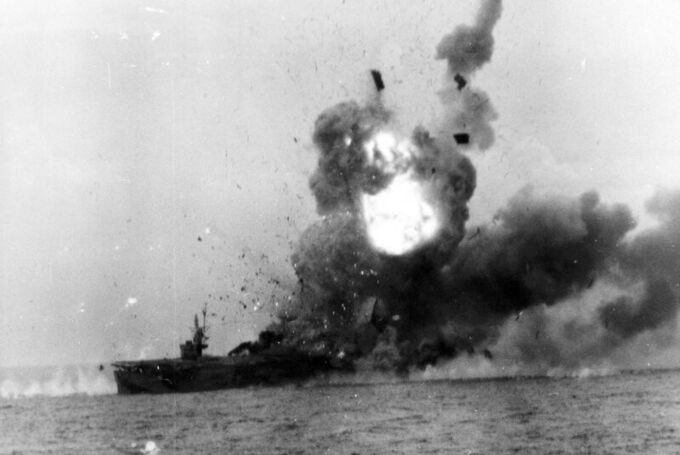

Their first mission was October 25 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The initial attack consisted of five A6M Zeroes; their targets were the American escort carriers. Out of the five, one Zero struck, and obliterated the carrier USS St. Lo.

By the evening of the next day, USS Sangamon, USS Santee, and USS Suwannee, all of which are escort carriers, were damaged. USS White Plains, USS Kalinin Bay, and USS Kitkun Bay were also damaged. More than thirty-five small escort ships were destroyed in the attacks.

Later Missions

While Japan was being bombed by B-29 Superfortresses, a new form of kamikaze was born: anti-air kamikaze. The Japanese loaded many Ki-44 Shoki interceptors with explosives and attempted to ram the B-29s. These were usually ineffective, as it is naturally harder to hit a fast, flying bomber than a slow, cumbersome ship.

In March 1945, the carrier USS Randolph and the submarine USS Devilfish were both hit, but not fatally.

After the shock of the attacks during Leyte Gulf, the Americans slowly developed weaponry to better combat kamikaze attacks, like proximity fuses on AAA shells.

The Peak and Fall of Kamikaze

Between April and June 1945, kamikaze was at its peak. 1400 aircraft were used during one mission in the Battle of Okinawa. The defense of Okinawa sank around 30 of the invading ships, but these were mostly smaller ships. The British carriers usually had higher survivability than their American counterparts, due to armored decks, so they naturally suffered less losses. USS Bunker Hill was hit critically by pilots named Kiyoshi Ogawa and Seizō Yasunori. Kamikaze tactics were now using any aircraft the Japanese could get their hands on, like bombers, and even trainers.

Most kamikaze attacks were unsuccessful, and most aircraft were destroyed before they found home on an enemy ship. Roughly 14%-19% of all attacks hit a target.

The last kamikaze attacks were used in August of 1945, against Soviet vehicles attacking from the West. By the end of the war, Japan had around 9000 stockpiled aircraft, waiting for the American invasion that never happened.

Specialized Kamikaze Aircraft

Although most kamikaze vehicles were simply normal air force or naval aircraft laden with bombs and explosives, the Japanese had created a few special weapons for niche kamikaze missions. The following only includes projects that were completed.

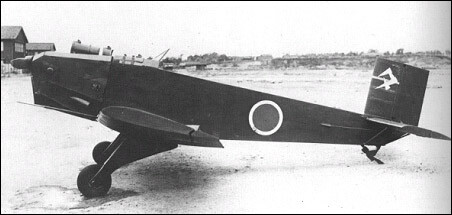

Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka

Perhaps the most well known kamikaze weapon, the Ohka (or "Cherry Blossom") was a small, single-seat, rocket-powered aircraft with a massive 2,600 pound ammonal warhead in the nose. It was powered by three Type 4 Mark 1 Model 20 solid-fuel rocket engines that could bring the MXY to speeds of up to 403 mph. While fast, the small aircraft couldn't take off on its own, or travel far on its own. This is why Ohkas were carried into battle by G4M "Betty" bombers, or P1Y "Ginga" bombers, and then released some distance away, so the MXY could gain speed while closing in on its target. It had to be manually guided to its target by a pilot, who would sacrifice himself to get his Ohka on target.

The only action the MXY saw was in Okinawa in 1945. They managed to cripple and sink a few escort ships, but didn't do any harm to the larger battleships. The unofficial Allied reporting name for the Ohka was "Baka," which was the Japanese word for "idiot" or "stupid".

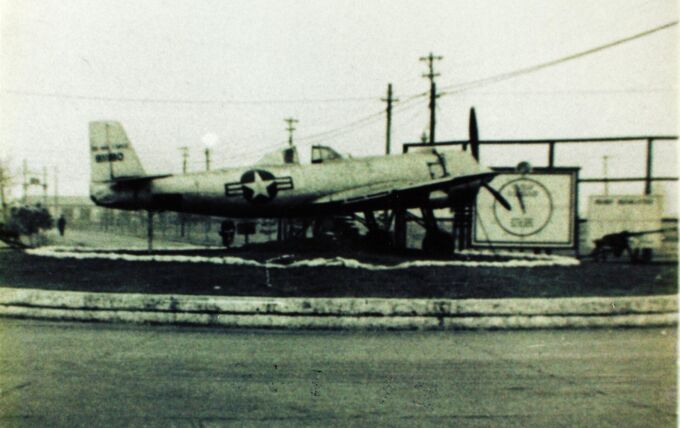

Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi

A lesser-known machine, the Ki-115 Tsurugi (or "Sword") was a one-man suicide plane designed by Nakajima. It was to be used against Allied vehicles during the anticipated invasion of Japan, which of course never happened.

The Ki-115 was built from wood and steel, so it could be built quickly on an assembly line. It had all necessary control surfaces, but they were all built rather crudely. It was designed to be able to hold a variety of engines, making it easier to operate and build.

While it had a top speed of 342 miles per hour, and could be equipped with rocket boosters, the rest of the performance was horrendous. It would have been easy to intercept if used in combat.

Kokusai Ta-Go (Ki-128)

The Ta-Go was developed in 1945 as a small, easy to mass produce kamikaze aircraft. It was built entirely from wood, so it could be hastily built in workshops.

The pilot would sit in an open cockpit, with simple instruments to aid his flight. The short wings could be folded in case it needed to be stored in a small space. All landing gears were fixed, and the fuel and oil tanks were held on to the top of the engine nacelle by mere metal straps. The engine was a tiny 4-cylinder inline engine that could bring the aircraft to 121 mph. There was no bomb release option for the 220 lb bomb, as it was a one-way trip.

Only one was built, and it was nearly completed, but destroyed by American bombs.

Previously Existing Aircraft

A number of previously existing aircraft designs were also typically used for kamikaze. These were usually fighters, and obsolete trainer aircraft, but heavy fighters and bombers were also used.

- Aichi D3A "Val"

- Aichi E13A "Jake"

- Kawasaki Ki-48 Sokei "Lily"

- Kyushu K11W Shiragiku

- Kyushu Q1W Tokai "Lorna"

- Mitsubishi A5M "Claude"

- Mitsubishi A6M Reisen "Zero"

- Mitsubishi Ki-15 "Babs"

- Mitsubishi Ki-21 "Sally"

- Mitsubishi Ki-30 "Ann"

- Mitsubishi Ki-51 "Sonia"

- Mitsubishi Ki-67 Hiryu "Peggy"

- Nakajima B5N "Kate"

- Nakajima B6N Tenzan "Jill"

- Nakajima C6N Saiun

- Nakajima J1N Gekko "Irving"

- Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa "Oscar"

- Nakajima Ki-44 Shoki "Tojo"

- Tachikawa Ki-9

- Yokosuka P1Y Ginga "Frances"

- Yokosuka D4Y Suisei "Judy"

- Yokosuka K5Y

Other vehicles

Not only were aircraft used for kamikaze, but speedboats, submarines, human torpedoes, and divers armed with mines were also experimented with.

Cultural Viewpoints

Overall, many young men (most of which were inexperienced pilots aged 25 or younger) were voluntary kamikaze pilots. Many pilots were taught that dying for the emperor was an honorable duty, and wartime ideology promoted the idea that fallen soldiers became protective spirits. However, postwar testimonies show that many felt conflicted or coerced.

Before every kamikaze mission, the pilots were given a celebration prior to take-off. They shared sake, or rice-wine, and wore a senninbari, or a headband given to them by their mothers. The pilots also wrote and recited death poems, similar to samurai. They took family prayers with them into combat.

The kamikazes were typically sent with escorts, who were usually sent out as kamikazes later on.

It is said that some pilots flew past a mountain that looked similar to Mount Fuji on their way to their targets, saluted the mountain, and said goodbye to their country before carrying on with the mission.

Kamikaze pilots who failed to finish their missions, for whatever reason, were stigmatized and treated poorly in the following years of the war. It started to go away around 50 years later, but only because survivor stories were shown to the public about their wartime experiences.

Notable Kamikaze Attacks

Although there were many kamikaze pilots throughout the war, here are a few interesting or notable occurrences.

Sakio Komatsu - Torpedo Interceptor

One rare incident involved a pilot reportedly intercepting an American torpedo with his aircraft. While ultimately unsuccessful, this act remains a controversial example of extreme wartime measures.

During the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Komatsu had to bank hard off the deck of the carrier he had just taken off from, as he had just seen six torpedoes fired from an American submarine not too far away. Komatsu was flying in his D4Y Suisei aircraft, en route to strike enemy ships. However, as soon as he saw the torpedoes, he was determined to save his aircraft carrier, the Taiho. He dove his D4Y into the sea, in an attempt to stop the incoming weapons.

Out of the six, four missed, one struck the Taiho, though not fatally, and Komatsu had stopped one; the one he stopped had detonated the moment he flew into it.

Unfortunately, the Taiho would later be bombed, and destroyed, but at least Komatsu's sacrifice kept his crew mates alive to fight a little longer.

Saburo Dohi - Ohka Experience

Having volunteered for a "special mission," Saburo Dohi was to go on a mission and use a top-secret weapon. Dohi would sink an entire destroyer with this weapon.

Dohi had volunteered in late 1944 for the Special Attack Unit, which was to use an all-new, top secret weapon on its missions. The weapon, of course, was the MXY Ohka suicide missile, which Saburo trained for via glider.

In 1945, a battleship was spotted not too far away from a flight of roughly 30 G4M bombers, each of which were equipped with one MXY suspended from the bomb bay. Saburo Dohi, who was to attack the ship following the initial attack by 3 A6M Zero kamikazes, thanked the bomber's navigator, who wished him luck. Dohi climbed into the Ohka, and took a deep breath.

Since the jettison devices had failed, Dohi was manually released from the G4M. As he fell, he activated the Ohka's three rocket boosters and sped for the target. As he closed the distance, he shut his eyes and exhaled deeply.

The Ohka struck the vessel, resulting in a massive explosion that destroyed it. Accounts from the G4M crew describe witnessing the impact and celebrating, even though such missions came at the cost of the pilot's life.

It was later revealed that the ship was USS Mannert L. Abele, and it was a destroyer rather than what the crew assumed to be a battleship.

Matome Ugaki - Admiral's Duty

After Hirohito had announced Japan's surrender in August 1945, Yamamoto's second-in-command, Matome Ugaki, blamed himself for letting the American Air Force advance so far into Japanese territory.

He decided that he would be loyal to the samurai code and commit kamikaze to make up for the dishonor he had brought upon his name. It was his duty.

He climbed into the back seat of a D4Y4 "Judy" dive bomber from the 701st Kotutai, piloted by Lieutenant Tatsuo Nakatsuru, and Warrant Officer Akiyoshi Endo at navigation. The D4Y took off in search of a target.

North of Okinawa, an enemy vessel was spotted, and Ugaki's "Judy," along with the rest of the crew, dove to the ship to fulfill their fates.

While no successful attack was reported that day, this mission shows just how determined and dedicated the higher-ranking Japanese were to their roles in the military.

Kamikaze War Cries & Headbands

While it's not entirely certain what most pilots said, if they said anything, in the last seconds of the attack. It's generally accepted that if a pilot said something they would have said:

"Tenno Heika Banzai!"

This cry translates to, "Long live the emperor, banzai!". "Banzai" was already a widespread term which meant "charge."

Hissatsu (必殺)!

This term, while not having a direct translation, basically meant "Strike true" or "Maximum damage."

Some kamikaze pilots wore special headbands, called hachimaki (鉢巻, "helmet-scarf"). They had a rising Japanese sun on a white background, and usually had an inspirational message on it. The pilots would put these on prior to the attack. This was inspired by samurai tradition.

Conclusion

The kamikaze strategy reflected a deeply rooted cultural emphasis on loyalty and sacrifice, shaped by wartime propaganda and traditional values. While controversial, these missions remain a powerful example of the extremes nations may reach during total war.

Japan developed a variety of purpose-built aircraft and repurposed existing models for these missions, reflecting the resource limitations and strategic desperation of the late war period.

I'm a huge fan of Japanese history. Let me know what you think about the Japanese kamikazes, or if you have anything you'd like to add.

Note: I've included all aircraft used for kamikaze present in War Thunder in the "Mentioned Vehicles" section at the bottom.

Have an awesome rest of your day!

Sources Used

- Matome Ugaki | Wikipedia

- This pilot crashed his plane into a torpedo to save the carrier | We Are The Mighty

- WW2 Kamikaze Aircraft | Military Factory

- Kamikaze | Wikipedia

- Life of a Kamikaze | Yarnhub - YouTube

- Japanese Special Attack Units | Wikipedia

- Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka | Wikipedia

- Nakajima Ki-115 | Wikipedia

- Kokusai Ta-Go | Wikipedia

- Kamikaze | Encyclopedia Britannica

- Seppuku | Wikipedia

- USS Mannert L. Abele | Wikipedia

- 8 Legendary War Cries | History.com

Disclaimer: I do not support or endorse kamikaze-like acts or strategies.