The Battle of the River Plate was the earliest major naval battle of the Second World War. It saw the sinking of German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee and is often touted as an early success for the Royal Navy, though the actual facts of the battle somewhat muddle that case. The story of this famous battle actually starts a few months before the day it took place on December 13, 1939.

Prelude

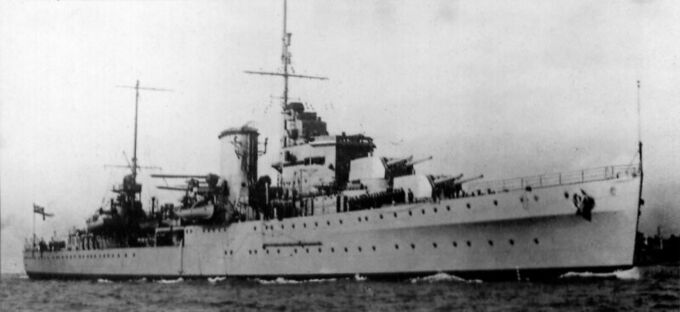

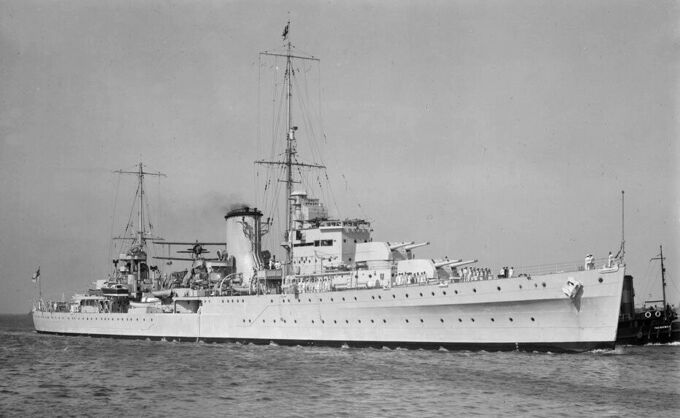

Force G was one of the many hunting task forces formed early in the war by the Royal Navy and was commanded by Commodore Henry Harwood. On October 5, 1939, the task force was formed with Leander-class light cruisers HMS Achilles and HMS Ajax, York-class heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, and County-class heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland. Harwood made Ajax his flagship late in the month.

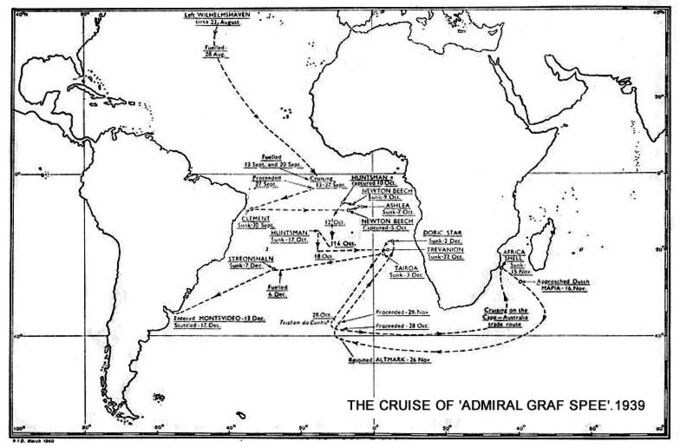

Force G was stationed in South America to protect transport between the River Plate—the choke point for all shipping heading for the capitals of Argentina and Uruguay—and Rio de Janeiro—the capital of Brazil. They had been patrolling South America following the sinking of the British merchant ship SS Clement southeast of the Brazilian city of Recife on September 30.

Following the sinking of British cargo liner SS Doric Star on December 2 off the coast of South-West Africa, now Namibia, Harwood suspected that traffic in the River Plate would be Graf Spee’s next target and set Force G on a course for its mouth. Harwood suspected this because, despite the Graf Spee signaling the Doric Star to cease transmissions, its captain, Willian Stubbs, refused and included in the morse code distress call that it was being attacked by either Admiral Graf Spee or its sister ship Deutschland, later renamed Lützow. Stubbs also included that the vessel appeared to be disguised as the British battlecruiser HMS Renown or its sister ship HMS Repulse due to it having a fake turret and smokestack fitted.

On December 9, Harwood ordered Exeter and Achilles to join Ajax just off the River Plate Estuary. Exeter and Achilles arrived on December 12 and Harwood called a council of captains to discuss the plan for if/when the Admiral Graf Spee arrived. Critically, the plan had to be formed around the fact that HMS Cumberland, the task force’s largest vessel, was not present since she was at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands for repairs.

The Battle of the River Plate: Minute by minute

Much of the following minute-by-minute recounting has been written using the book River Plate 1939: The sinking of the Graf Spee written by Angus Konstam and illustrated by Tony Bryan as a primary source. Additional information has been added using many of the other sources listed to create a complete picture of the engagement.

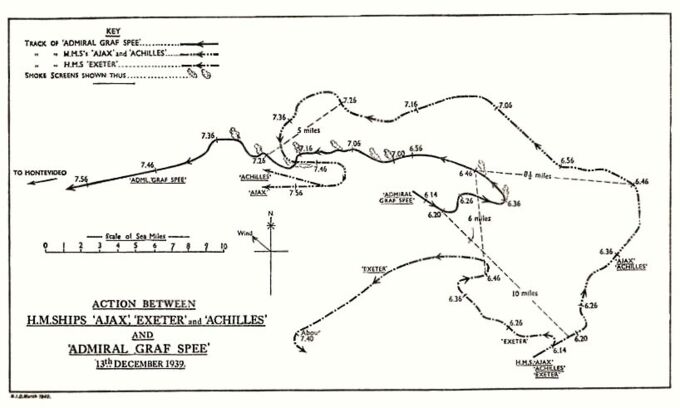

Some time between 6:10 and 6:14 A.M. on the morning of December 13th, Harwood’s ships sighted smoke to the north-northwest.

At 6:16, Exeter broke hard to port to engage the Graf Spee. This was part of a plan Harwood had devised and even taught for engaging pocket battleships. The plan was that Exeter would engage the Graf Spee on its starboard side and Ajax and Achilles would engage from the port. The goal was to both overwhelm the Graf Spee with the crossfire and to force the Graf Spee to split its fire between the 2 sides, reducing its combat efficacy.

At 6:18, Graf Spee opened fire, with Exeter returning the favor at 6:20. Achilles and Ajax opened fire in tandem at 6:22. At 6:23, Exeter was struck by Graf Spee’s third salvo, with Graf Spee receiving the same treatment from Exeter at 6:24.

At 6:25, a salvo from Graf Spee hit HMS Exeter’s B turret, taking it out, with the shrapnel heavily damaging the bridge. This damage also took out Exeter’s radio, killing both her ability to communicate with other ships and to communicate with her own crew, including cutting off Captain Frederick Secker Bell’s ability to give orders. Bell managed to reestablish communications, but not with the radio. Rather, in an incredible feat, Bell gave men that came up to him orders, told them to tell other people to give certain orders, and through that established a human chain of communication. Crew members of all ranks scurried across and throughout the vessel delivering maneuvering, gunnery, and damage control orders and updates, as well as continually delivering information back to Captain Bell and all other necessary personnel.

At 6:28, Graf Spee turned her guns to Ajax and Achilles. Exeter performed a torpedo charge at 6:32, but completely missed due to miscommunication from her delayed and damaged communication. At 6:37, Graf Spee made smoke and broke away from the British cruisers. Simultaneously, Ajax launched her Seafox Mk. I floatplane to survey the situation. Due to the inattention of certain members of the crew, radio connections were not established with the Seafox for the next 12 minutes.

Ajax was originally supposed to be fitted with 2 floatplanes, but they only ever managed to fit one to her.

Graf Spee then turned her guns back towards Exeter at 6:38, and Achilles and Exeter were both struck by fire at 6:40. Exeter lost her X turret and Achilles lost her gunnery director tower. Achilles' fire control was reestablished, but was then lost again when a radio link failed. This caused her to fall out of fire concentration without the knowledge of Ajax’s gunnery director. The confusion in Ajax’s gunnery director induced by this meant that for the next 25 minutes, Ajax fired incorrectly ranged salvos, not scoring a single hit. Even when radio connection with Ajax’s Seafox was finally established, the Seafox misidentified salvos and gave incorrect ranging instructions to Ajax, causing her to overrange her shots for 14 minutes.

At 6:43, Exeter made another failed torpedo charge and at 6:56, Graf Spee broke away from the cruisers and made smoke. Despite the smoke clouding their vision, Harwood, likely suffering from status-quo bias, refused to close the distance despite being more than 13,700 meters away from the Graf Spee. For a total of 42 minutes, Ajax and Achilles likely did not score a single hit on the Graf Spee, and certainly no detrimental ones.

Finally, at 7:14 A.M., a full hour after Force G first made contact with the Admiral Graf Spee, Harwood ordered Ajax and Achilles to maximum speed and to close the distance to under 9,000 meters, saying, “Proceed at utmost speed.” It began to work. At 7:18, Graf Spee began being raked with fire from Ajax and Achilles. They consistently scored hits and heavily damaged Graf Spee due to their more rapid fire rate and superior number of main caliber guns, even though their 152 mm main batteries were dwarfed by Graf Spee’s 283 mm battleship-caliber cannons.

At 7:22, HMS Ajax entered position for a torpedo charge and fired off 4 torpedoes from its port launching tubes. The Graf Spee broke west and made further smoke. At 7:25, shells from Admiral Graf Spee hit Ajax’s X and Y turrets, knocking both out of commission, and at 7:30, Exeter’s Y turret, its last working turret, suffered a power failure due to water entering and short circuiting the turret drive’s electrical systems. Exeter’s last working turret was no longer able to traverse.

At 7:32, Graf Spee launched torpedoes at Ajax and Achilles. She subsequently ceased fire while continually being pummeled by Ajax and Achilles. But then, at 7:38, Harwood ordered Ajax and Achilles to cease fire. Harwood had received a report that HMS Ajax was on 20% ammunition. Harwood was rightfully worried that he would not have enough ammunition to defend himself, but victory was nigh and 20% ammunition in his main battery was more than what was needed to sink the Graf Spee. This 20% report was also an error as it only applied to one turret. Ajax had 50% of its 152 mm ammunition left and Achilles 30%. Not all of Ajax’s 50% ammunition was usable because its X and Y turrets were out of commission, but it still had enough to sink the Graf Spee. Furthermore, this predicament was Harwood’s fault to begin with. Harwood closed to extremely close range without checking that he had the ammunition to do so, only after having stayed at long range for far too long, exhausting vast ammunition stores without any hits for almost an hour.

At 7:40, Exeter broke off combat, with Ajax and Achilles making smoke at 7:45. At 7:49, the Graf Spee ceased fire and began steaming towards the port city of Montevideo—the capital of neutral Uruguay—and at 7:50, Harwood ordered Ajax and Achilles to give chase. 20 minutes later, Ajax’s Seafox returned a report on the condition of HMS Exeter. It was extremely bad. Exeter was brutally damaged.

Nearly 2 hours later, at 10:00 A.M., Graf Spee briefly opened fire on HMS Achilles. At 11:07, Exeter managed to reestablish radio contact with HMS Ajax. Harwood requested fire support from Exeter at 11:15 but was told, “All guns out of action.” At 1:40 P.M., Harwood finally ordered Exeter to break off from the engagement and head to Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands for repairs. At 7:15 P.M., the Graf Spee turned her fire on HMS Ajax.

At 8:10, Harwood ordered Ajax to break away. Achilles was the only ship left pursuing the Graf Spee. At 8:48, Graf Spee and Achilles opened fire at each other, and starting at 9:30, Graf Spee fired a series of salvos from her main batteries. At 10:00 P.M., Achilles set herself at 9,000 meters astern of the Graf Spee. At 10:40, Graf Spee reached the entrance to the port of Montevideo and requested permission to enter. At 10:45 Harwood ordered Ajax to break southeast. This ended British military engagement with the Graf Spee and with it, the Battle of the River Plate.

Finally, at 11:45 P.M., the Graf Spee received permission to enter the port of Montevideo. Had HMS Cumberland been there to execute the port flank along with HMS Exeter, Graf Spee almost certainly would have been sunk.

Stuck in port

While that was the end of Force G’s direct involvement with the Admiral Graf Spee, that was not the end of the Graf Spee’s story. On December 14th, HMS Cumberland joined up with the rest of Force G, and Force K was ordered to the River Plate from its station in Pernambuco, Brazil, to the north. The British also began broadcasting easy-to-intercept radio signals stating that Force K, comprising aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal and battlecruiser HMS Renown—a ship capable of extremely badly damaging or possibly sinking even a fully combat-ready Graf Spee—were in the region. In fact, Force K was only expected to arrive on December 19 and Uruguayan authorities had given the Graf Spee’s captain Hans Willhelm Langsdorf only 72 hours—until the evening of December 17—to depart.

The bluff worked. Langsdorf ruled out fighting his way to more pro-Germany Argentina because he believed that HMS Renown’s guns and HMS Ark Royal’s aircraft stood in his way. The British stopped diplomatically pressing for the Graf Spee’s departure on December 15, but the ruse of Renown and Ark Royal being in the area had already done its job. At 6:30 P.M. on December 17, the Graf Spee sailed out to sea with a skeleton crew of roughly 40 men and they began setting scuttling charges at 7:54. At 9:30 P.M., all crew abandoned the Graf Spee six and a half kilometers offshore. The crew sailed a kilometer and a half away from the Graf Spee and, at 11:00 P.M., the scuttling charges were detonated. The turrets exploded off of the ship and a cloud rose 300 meters into the air. The wreck of the Graf Spee burned in the water for 2 days.

Aftermath

The surviving crew of the Graf Spee, including Langsdorf, arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on December 18, but instead of receiving the heroes' welcome they had hoped for, they were labeled cowards in the media and German high command blamed Langsdorf for the Graf Spee’s loss. Furthermore, Argentinian authorities told him that he and the crew faced imprisonment.

On the evening of December 19, Langsdorf retired to his room in a Buenos Aires hotel. He wrote a letter to his wife, a letter to his parents, and a letter to the German ambassador. His letter to the German ambassador explained his rationale behind scuttling the Graf Spee. In it, he wrote, “I alone bear the responsibility for scuttling the panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee. I am happy to pay with my life for any possible reflection on the honor of the flag. I shall face my fate with firm faith in the cause and the future of the nation and of my Führer.” Langsdorf then laid the German Naval Ensign on his desk and pulled out a revolver. His body was found the next morning in his hotel room.

The Battle of the River Plate was a strategic success for the British. Germany lost one of their best commerce raiders and one of its symbols of power. It was also a propaganda success, with the British claiming in propaganda that Ajax, Achilles, and Exeter had extremely precise fire the whole time and won handedly.

The truth is that, while the sinking of the Graf Spee was an overall strategic success for the allies, the battle itself was a British tactical failure. Harwood cannot be blamed for applying pre-war naval doctrine designed for that specific situation at the outset of the war. However, once his plan was in motion, he failed to realize that it was not working and continued having Exeter execute the starboard flank for far too long, did not come to Exeter’s aid until far too late, did not establish proper radio communication with Ajax’s Seafox for 12 minutes, fired his main batteries into the blue for 42 minutes, and then closed to short range without properly making sure he actually had the ammunition remaining to do so. Stuck in the depths of status-quo bias and confirmation bias about his plan, he failed to realize its shortcomings despite having firepower, numerical, and positioning advantages. Ultimately, he let the Graf Spee escape, despite having enough ammunition to finish it off with rounds to spare.

The actual loss of the Graf Spee was only partially Harwood’s doing and had it not been for the British bluff about Force K or had Langsdorf called the bluff, the Graf Spee may very well have survived by escaping to Argentina. Harwood is the one who correctly predicted where the Admiral Graf Spee would sail to next following the sinking of SS Doric Star. However, Harwood was not lionized for that foresight, at least not in large part. Rather, he was lionized for his actions in the battle itself—actions which were overstated and embelished to justify that lionization. Harwood was promoted to Rear Admiral and received a knighthood for his service in the battle.

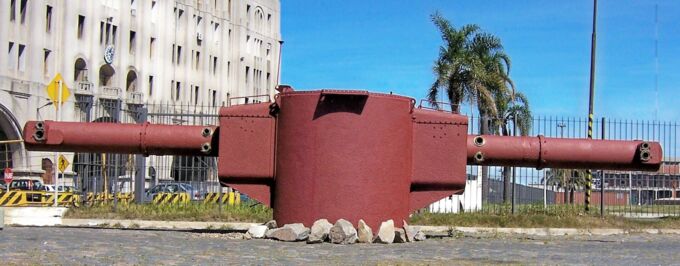

Raising pieces of the Admiral Graf Spee

In February 2004, a salvage team began working to raise certain pieces of the Admiral Graf Spee, with attempts beginning on February 9. After multiple failed attempts, the first piece to be raised—a 27 tonne optical rangefinder—was recovered on February 25. Today, the rangefinder can be seen on display in Montevideo. Then, on February 10, 2006, the vessel’s eagle crest was lifted from the water. The eagle crest is not on display due to complaints received about its iconography after it was put on display for a month in a Montevideo hotel. Instead, it resides in a naval warehouse.

The crest has been the subject of legal battles for years. The eagle, originally mounted on the Graf Spee’s stern, has sat in legal limbo as the Uruguayan government, the company that salvaged it, and several third parties have fought in court over whether it can be sold, and if so, to whom. Originally, after an attempt to sell the eagle, Uruguay prohibited any sale of it to avoid it falling into the hands of neo-Nazis. Then, in 2019, a court ordered that the eagle be sold and that a portion of the revenue from that sale be given to the salvage company. Following objections by Jewish groups and the German government, a ruling by a higher court overturned the sale, granting full custody of the eagle to the Uruguayan government.

On January 2, 2022, Jewish businessman Daniel Sielecki offered to buy the eagle, stating that he wanted to blow it up into, “a thousand pieces.” However, this sale never materialized. On June 17, 2023, the Uruguayan government announced that the eagle would be given to artist Pablo Atchugarry to be melted down into a dove. A day later, Uruguayan president Luis Lacalle Pou said this plan would not be carried out, citing a lack of consensus on the decision. Currently, the eagle still sits in a warehouse, awaiting a decision by the Uruguayan government.

Conclusion

The Battle of the River Plate may have been a tactical failure, but it nonetheless remains an important part of the history of the Second World War. It was the first major naval battle of the war, a propaganda success for the British, and a loss for the Germans, both strategically and in terms of what the Admiral Graf Spee represented as a symbol of the Third Reich’s power. Recounting and analyzing the history of this engagement and its ripple effects serves not only to deepen understanding of how actions early in the war had larger consequences across and beyond it, but also to shine a light on the often neglected role of South America in the war.

Sources

- House of Lords. (1947, January 29). Transfer Of Naval Vessels. Hansard, vol. 145, col. 281-302.

- House of Lords. (1948, June 1). H.M.S. “Ajax”. Hansard, vol. 156, col. 18

- House of Commons. (1948, September 22). H.M.S. “Ajax” (Sale). Hansard, vol. 456, col. 870.

- House of Commons. (1948, December 8). H.M.S. “Ajax”. Hansard, vol. 459, col. 381.

- House of Commons. (1948, December 15). H.M.S. “Ajax”. Hansard, vol. 459, col. 1179-1180.

- House of Commons. (1949, March 23). H.M.S. “Ajax”. Hansard, vol. 463, col. 358-359.

- House of Commons. (1949, April 6). H.M.S. “Ajax”. Hansard, vol. 463, col. 2027-2028.

- Aircraft of Ajax and the Ships at the River Plate. (n.d.). HMS Ajax & River Plate Veterans Association.

- de los Reyes, Ignacio. “What Should Uruguay Do with Its Nazi Eagle?” BBC News, 2014.

- H.M.S. Ajax (1934). (2021, February 26). The Dreadnought Project.

- HMS Ajax, British light cruiser, WW2. (2011, June 3). Naval-History.net.

- HMS Ajax VII — The Cruiser. (n.d.). HMS Ajax & River Plate Veterans Association.

- Konstam, A. (2016). River Plate 1939: The sinking of the Graf Spee. Osprey Publishing.

- Lissardy, G. (2022). ¿Cómo se vende un águila nazi? El problema que debe resolver Uruguay en medio de una controversia internacional. BBC News Mundo.

- Supplement to the London Gazette, 20 March, 1940. (1940, March 20). The London Gazette, 1702.

- Schuetze, C. F. (2023). Uruguay Will Turn a Bronze Nazi Eagle Into a Dove. The New York Times.

- Warship Reported in the Atlantic. (1939, October 3). Liverpool Daily Post.

- Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Naval Institute Press.

- Zimm, A. D. (2019, August). A Battle Badly Fought. Naval History Magazine, 33(4).