The P-51C-11 “Evalina”, named after the girlfriend of 1st Lt. Oliver E. Strawbridge, was captured by Japanese forces in China on 16 January 1945 while being flown by 2nd Lt. Sam McMillan. As the first fully functional P-51 to fall into Japanese hands, it was quickly repaired and transported to Japan for extensive evaluation, including performance trials and mock dogfights against domestic fighters. Evalina became a valuable tool for developing counter-strategies against the Mustang, one of the few Allied aircraft tested this thoroughly by Japan. Eventually, her generator failed during training, and with no replacement parts available, she was abandoned and reportedly bulldozed into a lake before the war’s end.

I had such confidence with this P-51 that I feared no Japanese fighters.

Introduction

By early 1943, the skies over the Pacific had changed. The Japanese Imperial Army Air Service (IJAAS) now faced a new and formidable adversary — the North American P-51 Mustang. While initial engagements still favored Japanese pilots flying nimble craft like the Ki-43 or the Ki-61, the balance began to tilt sharply as the Allies introduced the Merlin-engined P-51B, C, and eventually D models.

The P-51 quickly proved itself as a high-altitude escort, dogfighter, and ground attacker. Its range, speed, and reliability overwhelmed many Japanese fighter squadrons. Though Japan had recovered a few wrecked Mustangs from battlefields, none had survived in a condition that would permit real technical study.

That is, until early 1945 — when fate delivered a flyable Mustang nearly intact.

P-51C-11-NT “Evalina”

Japanese Capture

On January 16, 1945, during operations in Hubei Province, China, a P-51C-11-NT, serial number 44-10816, piloted that day by 2nd Lt. Sam McMillan Jr., was struck by Japanese anti-aircraft fire and forced to emergency-land in a rice field near the Japanese-held Suixian (隨県) airfield. The aircraft belonged to 1st Lt. Oliver E. Strawbridge of the 26th FS, 51st FG, 14th AF, and had been affectionately named “Evalina” after his girlfriend.

While reports aren't detailed about the "crash landing," the fact that the plane remained mostly functional and the underbelly radiator was undamaged suggests that the landing was performed with the landing gear down.

McMillan was captured and later became part of the infamous group of POWs known as “The Diddled Dozen,” sent to Japan for special interrogation. But for the Japanese, the bigger prize was the Mustang itself — their first intact P-51.

Upon hearing of the aircraft’s capture, the Imperial Japanese Army Aviation Headquarters ordered it transported to the home islands for testing. Though initial plans called for sea transport, the loss of control over the East China Sea rendered that route too risky. Instead, a covert overland airlift was planned.

The Army Inspection Department Fighter Squadron assigned two key figures to the mission, familiar with inspections on liquid-cooled aircraft:

- WO Etsuji Mitsumoto — Pilot (Ki-60)

- 2nd Lt. Masao Sakai — Maintenance & repair (Ki-60 & Ki-61)

They were accompanied by an interpreter, captured pilot McMillan, support mechanics, and 30 infantrymen for security. Evalina, already partially dismantled for concealment, was moved by rail and truck to Hankou. Despite nearly a dozen P-51 interception attempts during transit, the aircraft survived undamaged.

After being reassembled in Hankou, Evalina was flown to Fussa Airfield (present-day Yokota) by early March 1945, setting the stage for one of the most thorough evaluations of an Allied aircraft conducted by the Japanese military during the war.

Technical Evaluation in Japan

Once in Japan, she was quickly evaluated alongside other aircraft at Fussa including:

- Fw 190 A-5 (Imported)

- P-40E (Captured)

- Ki-61 “Hien”

- Ki-84 “Hayate”

All aircraft lined up at 5,000 meters. While the Fw 190 leapt ahead at first, by the end of the 5-minute test, the P-51C had pulled far ahead of all others. Pilot impressions included:

It’s easy to fly, has excellent speed and maneuverability, and it’s hard to find any flaws. — It’s similar to the Ki-61 prototype, which doesn’t have any weapons or radios or other equipment.

A harmonized, superb fighter. Compared to the Ki-84 in horizontal turns, it was evenly matched at +200mmHg boost, but if you use high-octane fuel, which is out of reach in Japan, with +400mmHg, the P-51C wins.

The Army Evaluation Board concluded that only the Ki-100 could match Evalina’s performance.

Evalina Goes to War — Again

By April 7, 1945, following the first P-51D incursions over Japan, Kuroe was ordered to take Evalina on a domestic tour of fighter units across Japan. Her mission: to act as an aggressor aircraft in mock combat training — helping Japanese pilots understand how to fight the Mustang.

Evalina was flown across several bases:

- Chōfu (244th Sentai)

- Kashiwa (18th, 70th Sentai)

- Shimodate (51st, 52nd Sentai)

- Akeno Army Flying School

- Itami (56th Sentai)

- Ōsaka Taishō (256th Sentai)

In one mock engagement, Capt. Masashi Sumita of the 18th Sentai attempted to intercept Evalina together with Lt. Nakamura in two Ki-100s. Starting from a lower altitude, the Ki-100s managed to get behind Evalina briefly — but the Mustang executed a dive and climbing loop, regaining the advantage and slipping behind its pursuers.

You need to remember your opponent’s speed and climbing ability well. If it had been a plane of the same level, you might have won, — but if the opponent was a P-51, that’s what happened, so be careful.

One other pilot of the 18th Sentai, 1st Lt. Masatsugu Sumita, recalled that he learned “how to take his aircraft out of the P-51's axis when being chased…”.

“Low-altitude fights are dangerous against it — but with altitude advantage, I think we have a chance.”

— Cpt. Haruo Kawamura

before being taken aback by the words:

“That Mustang was only running at 80% power… It wasn’t even giving everything, so be careful in actual combat.”

— Maj. Sakai

Even Instructor Yohei Hinoki of the Akeno Flying School, the “iron-legged ace” who shot down the first Mustang, flew Evalina and remarked:

Major General Imagawa asked me to master the P-51 and then demonstrate it to other fellow pilots. I did not have a great deal of confidence in my ability to fly such an advanced aircraft with my disabled leg, but I made up my mind to do my best.

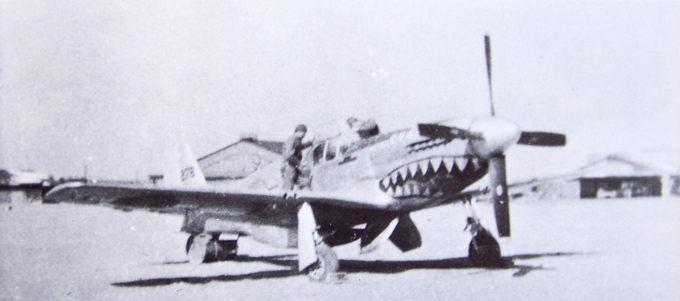

I flew to Omasa airfield and finally got a look at the P-51. I could see the superiority of its equipment, and its shiny fuselage with the open red mouth of a dragon. I saw several red dots on the side of the cockpit, probably recording Japanese aircraft the pilot had shot down. With the radiator under the fuselage, it looked very sleek and deadly.

It reminded me of the day I had first seen the P-51 in the sky above Burma on 25 November 1943. Major Kuroe, who brought the P-51 back from China, told me how easy the P-51 was to fly. Getting in, I was very impressed by the roomy seat and I did not have any trouble with my artificial leg on the rudder pedal. For me there were several new things about the aircraft. First of all there was the bulletproof glass, with a better degree of transparency than the thin Japanese glass; secondly, the seat was surrounded by a thick steel plate which I had never seen in a fighter before; there was an automatic shutter for the radiator, and an oxygen system which was new to me. Overall, it was better equipped than any Japanese airplane I had ever seen.

The End of Evalina

Tragically, while performing exercises at Taishō Airfield, Evalina’s generator burned out and forced an emergency landing. With no replacement parts, it was abandoned until the end of the war as it was unable to fly. Major Kuroe was still undergoing inspections for the Ki-102 and Ki-106, so it was planned to hand it over to the Akeno Army Flying School for research and training, but it never made it there with the end of the war.

She was likely abandoned or buried, possibly bulldozed in a lake or hidden field, her fate sealed like many relics of the Empire’s final days.

Legacy

Evalina remains one of the most thoroughly studied Allied aircraft in Japanese hands. Her capture provided the IJAAS a unique glimpse into the technological edge they faced — and offered a rare training opportunity for elite pilots in Japan’s waning months of war.

While rumors exist of additional P-51D Mustangs being captured late in the war, none were ever tested, evaluated & trained on as extensively — or left behind such a story.

Aftermath

Oliver E. Strawbridge & Sam McMillan

For decades, it was widely assumed that 1st Lt. Oliver E. Strawbridge, Evalina’s namesake pilot, had been the one flying the P-51C when it was captured. This belief remained unchallenged until the mid-1990s, when Sara Strawbridge, his granddaughter, clarified the record. Despite never having met her grandfather, Sara confidently stated that Strawbridge was not flying Evalina on January 16, 1945, nor was he ever a prisoner of war in Japan. In fact, she explained, he had survived the war, remained in the U.S., and died in 1987.

While he had named the plane after his then girlfriend—Evalina—the relationship had ended, and he later married a woman named Ruth Anne.

This revelation prompted aviation historian Henry Sakaida to dig deeper. His research ultimately identified 2nd Lt. Sam McMillan, a close friend of Strawbridge’s and fellow pilot from the 26th FS, as the actual pilot that day. McMillan had been shot down, captured, and held as a POW in Japan. He survived the war and returned to Connecticut, though by the time of Sakaida’s inquiry around 2000, he was elderly and in poor health, unable to recount the incident further. Sakaida published these findings in Flight Journal, thanks in large part to archival assistance from Susan Strawbridge-Bryant, a family relative.

Yasuhiko Kuroe

Major Yasuhiko Kuroe, the ace who brought Evalina to Japan and led its evaluation and combat training missions, was officially credited with 30 aerial victories, including three B-29 bombers. Beyond Evalina, he was involved in evaluating key late-war interceptors like the Ki-102, Ki-106, Ki-109, and the rocket-powered Ki-200.

Following Japan’s surrender, Kuroe returned to his rural hometown and took up farming, raising horses and cultivating the land. Like many in postwar Japan, he struggled with poverty and food shortages, eventually falling into debt through a series of unsuccessful business ventures including peddling and salvage work.

His fortunes changed in 1954 when he joined the newly formed Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF). He regained his health, resumed flying, and rose rapidly through the ranks. As a jet pilot and later a squadron commander, Kuroe even studied with the Royal Air Force in the UK, gaining international experience.

By 1965, he had become a Colonel of the 6th Air Wing stationed at Komatsu Air Base, a candidate for future high command. Yet fate intervened again. Ignoring weather warnings, Kuroe went fishing off the Echizen coast of Fukui Prefecture on December 5, 1965, and was tragically swept away by high waves. He was just 47 years old.

His funeral was conducted with full military honors. During the ceremony, the song of the 64th Sentai, written by Kuroe himself during the war, was solemnly performed—an echo of a man who had once danced through the sky in Evalina.