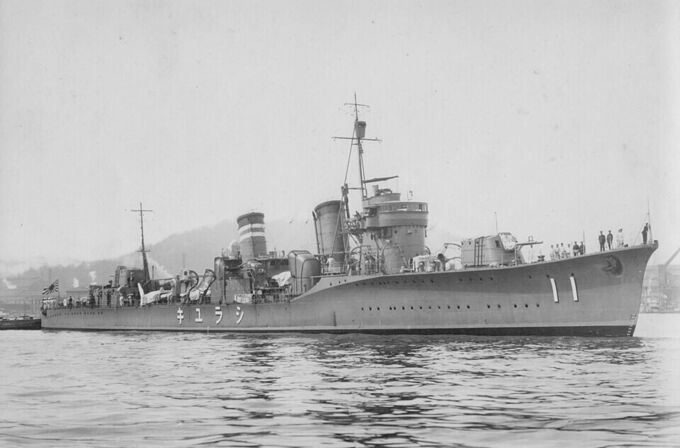

In 1928, a newly commissioned Japanese destroyer would change the way the Imperial Navy, and navies across the world viewed their destroyers. At 1,750 tons standard displacement, the IJN packed their new ship with six 5-inch guns in three waterproof mounts and three 24-inch triple-torpedo tube mounts with a reload for each tube for a grand total of eighteen torpedoes, a significant increase in armament compared to her contemporaries. The world had been introduced to IJN Fubuki, first of the so-called special-type destroyers.

Background

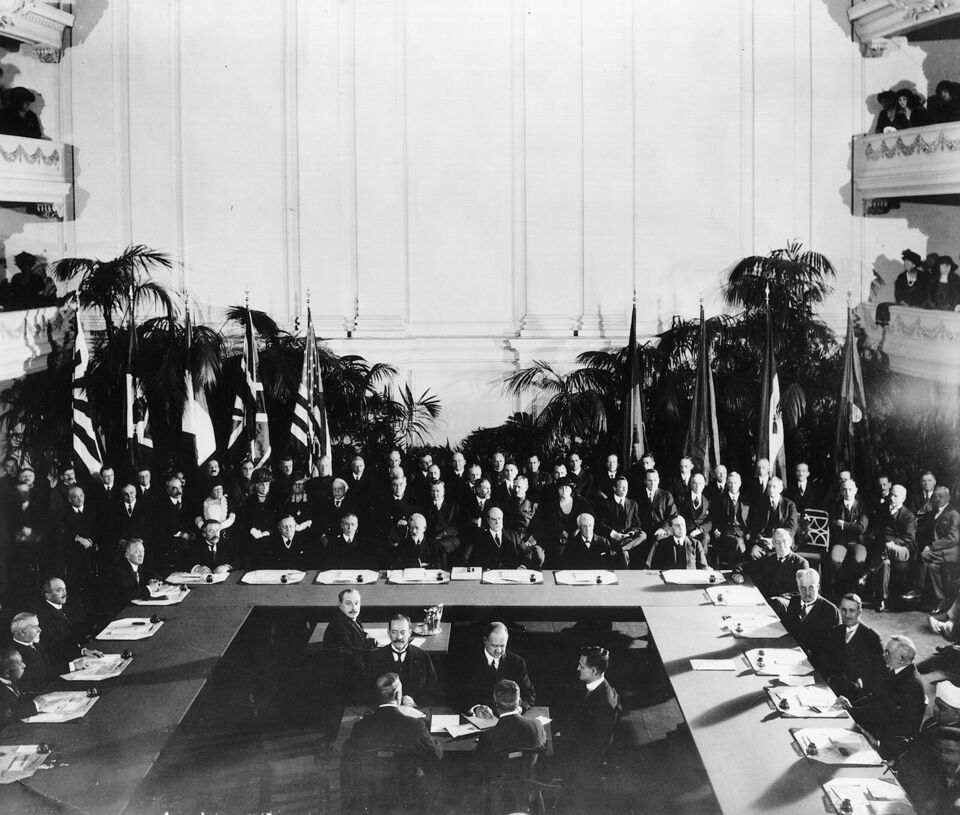

The year is 1922 and the world’s foremost naval powers have gathered together in Washington to sign the Treaty for the Limitation of Naval Armament, also known as the Washington Naval Treaty. The United States, the British Empire, the Empire of Japan, the French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy agreed to set hard limits on capital ships in order to prevent a naval arms race. Japan, then the third largest navy globally, left negotiations with some pretty heavy concessions. The United States refused negotiations unless the Anglo-Japanese Alliance was ended and the tonnage for capital ships Japan was allowed to retain was lower than the United States and Britain. The Imperial Navy was only allowed a combined capital ship displacement of 315,000 tons while the US Navy and the British Royal Navy were each allowed 525,000 tons.

It should be noted here that the treaty, and this article, is discussing standard displacement. Standard displacement is what the ship displaces when manned, armed with ammunition and loaded with stores but critically not including boiler feed water or fuel. This distinction is very important when it comes to the British, which would use water filled torpedo bulges to save more of their tonnage allowance under the treaty. This form of “evasion” was not unique among signatories, and Japan themselves would also engage in similar techniques to push what was allowed under the rules. But with a deficit of over 200,000 tons, the Imperial Navy were faced with a problem. The tonnage limits locked Japan, who viewed the United States as a likely enemy in a future war, into an uncomfortable position of inferiority, leading to many inside the IJN to wonder how to bring the balance back in their favour.

The answer was deceptively simple. The Washington Naval Treaty focused on aircraft carriers, battleships and battlecruisers, but did not set as many limits on smaller surface combatants. There were no limits on how many cruisers or destroyers a navy could have, only that they were to be kept under 10,000 tons each and have a gun armament calibre no greater than 8 inches. The Japanese would seize upon this and surmised that their best hope was by building their smaller surface ships with as heavy an armament as possible.

And so by October 1922, just months after the treaty was finalized, the designers of the IJN got to work.

Design and Construction

The design the IJN settled on was of 1,750 tons displacement, which was quite a bit heavier than the Mutsuki-class destroyers, which preceded Fubuki, at 1,315 tons. The Fubukis were also no slouch either, with a maximum speed of 35kts which, while slightly slower than her younger cousins, was by no means slow. Where the Fubuki class really shone, however, was with their considerable arsenal.

Starting with the torpedoes, each ship of the Fubuki class had three triple-mounted 24-inch torpedo tubes. If that wasn’t enough, each torpedo tube could be reloaded once each for a total load of eighteen torpedoes carried, per ship. Japanese destroyers where quite unique in that aspect, as many other navies, such as the Royal Navy and the US Navy, would only reload torpedo tubes in port, whereas the Japanese could do so at sea. The torpedoes fired by the Fubuki Class were in fact the infamous Type 93s, also known as the Long Lance, which probably deserve their own article to do them justice.

The Fubuki class’s gun armament was a step up as well. The 5-inch calibre were the largest guns fitted to a destroyer at the time, and they carried six of them in three double-mounts. These mounts were also an innovation for being the first enclosed weatherproof mounts for guns fitted to a destroyer. Gunnery crews until that point were in fact exposed to the elements, so one can imagine they appreciated that design aspect! The mounts, however, were not shell or even bulletproof, being only 3mm thick at its thickest.

Earlier ships of the class would be fitted with the Type A mount, a boxier design with a maximum elevation of 40 degrees, suitable only for low angle targets or surface targets only. Later Fubuki-class ships would employ the Type B mount, which had a maximum elevation of 75 degrees and theoretically could allow for dual anti-surface and anti-air usage of the main battery. However, in practice, the mounts were too slow to be trained and elevated against aircraft. The Type B’s can be distinguished by the flatter look compared to the Type A’s. In War Thunder IJN Ayanami is equipped with the Type B mount.

However, as impressive as the Fubukis' anti-surface armament were, their anti-air capability was rather underwhelming. Initially they were armed with only a pair of 7.7mm machine guns. This would quickly prove to be completely ineffective, and over the course of the Pacific war multiple refits across the class would attempt to fix this by either bolting on more machine gun mounts, including 13mm machine guns and the ubiquitous Hotchkiss style Type 99 25mm guns, often with surface armament removed to make more space. While initially envisioned that the main 5-inch guns were going to be able to engage air targets, it was soon found, as previously mentioned, unsuitable for the task.

The Fubukis would be built between 1926 and 1932, with the IJN Fubuki being completed first in October of 1928. The class would undergo several modifications in design over the course of construction, resulting in the ships being broken into three groups. Group 1s were typically the earlier built ships equipped with the Type A mounts, with the last ship, IJN Uranami, being built in 1929. The Group 2 ships were built with the Type B mounts, a larger bridge, and also had a modified air duct and ventilation system, however some later Group 1 ships like Uranami would also have this. A third group was also in existence, however these are generally considered its own separate sub class known as the Akastuki class, which we won’t be covering as they are rather different compared to the rest of the Groups.

The original design of the Fubuki class had the standard displacement at 1,750 tons, however they often came out of the shipyard overweight. This issue was most notable in the Groups 2s with their enlarged bridge and heavier Type B mounts. Overall across the class ships would be approximately 200 tons heavier in terms of displacement however this would vary from ship to ship.

The Fubukis would be built in shipyards across Japan, from Sasebo to Osaka, to Tokyo and Yokohama. However, it would not be long after Fubuki was completed that a few issues began to materialise. The Fubukis were coming up overweight, 200 tons overweight, and their impressive armament was making them rather top heavy. This was a major stability concern. This issue would come to a head during a typhoon on September 26th, 1935, when two special type destroyers of the design lost their bows and a further three received severe damage. As a result of this incident the entire class between 1935 and 1938 would return to the yards for hull-strengthening and top weight reduction measures. Whilst these changes would improve overall stability, it would ultimately increase overall weight with some of the Group 2 ships topping out at a standard displacement of 2090 tons.

In total 20 ships would be built, excluding the Akastuski sub-class, and the names and groups were as followed:

| GROUP 1 | GROUP 2 |

| Fubuki | Ayanami |

| Shirayuki | Shikinami |

| Hatsuyuki | Asagiri |

| Miyuki | Yugiri |

| Murakumo | Amagiri |

| Shinonome | Sagiri |

| Usugumo | Oboro |

| Shirakumo | Akebono |

| Isonami | Sazanami |

| Uranami | Uraga |

Service

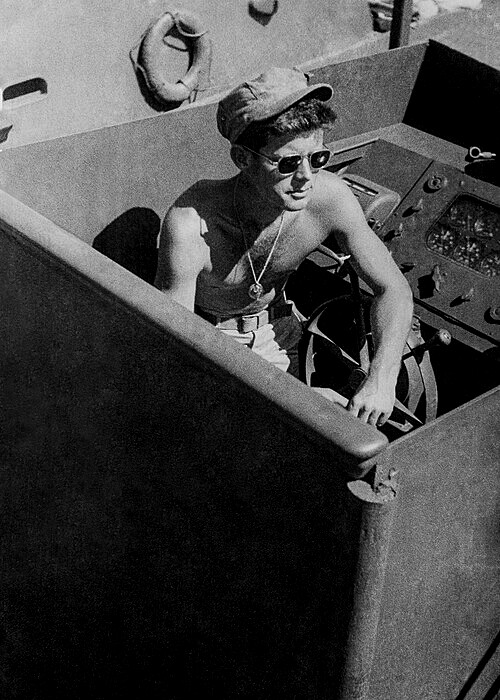

The Fubuki class, like many of the IJN’s destroyers, served wherever the Japanese fought. From the beginning, ships of the Fubuki class participated in the opening bombardments of Allied forces across the Pacific and escorting initial invasion forces in the East Indies, with the first loss to an air attack as early as December 18th in the case of IJN Shinonome. As the war dragged on, the Fubuki’s would be pressed into dropping supplies off for the army in Guadalcanal in what would be later known as the Tokyo Express. It was during one of these missions were the IJN Amagiri would ram and sink PT-109, commanded by future president John F. Kennedy.

As the course of the war worsened for Japan, the ships of the Fubuki class began to be thinned out more and more, with surviving units being pushed back with the rest of the IJN further and further North towards the Philippines. The lack of anti-aircraft armament certainly didn’t help with the attrition rates as the US began to dominate the Pacific skies, leading to further losses in-keeping with many other IJN ship classes at the time.

By the war’s end, 19 of the 20 ships were sunk, with only IJN Ushio surviving, albeit in an unrepaired state from a previous air attack in late 1944. The leading cause in ships being lost was air attack, with seven ships being sunk in this way, followed closely by submarine activity with six losses.

The Fubuki class design would be adapted, updated and upgraded by the IJN and its future destroyer programs until the lack of resources brought on by the Pacific War halted its ambitions. However, the pioneering design of the Fubukis, especially with its enclosed mounts and the intent of a dual purpose gun, would be seen in other navies efforts around the world, including, ironically enough, the United States, which had been the reason the Japanese pursued this design in the first place!

Sources:

- Imperial Japanese Navy Destroyers 1919-45 (1) by Mark STILLE ISBN 878-1-84908-984-5

- The Washington Naval Treaty

- Combinedfleet.com