So you know that weird, fugly boat tank that looks like an M18 and a Ka-Chi had a kid and then went to the store for milk? Let’s talk about that.

Table of contents

Who needs an amphibious tank destroyer?

In 1943, as the M18 was still in development, America was beginning to kick its Pacific island-hopping campaign into full gear. Tank destroyers, generally speaking, were not particularly well received in the Pacific Theater, nor was there much of a demand. The Japanese armor threat was minimal anyway and American tank destroyers with their open tops were highly vulnerable to the very potent anti-armor tactics of the Japanese infantry. Nonetheless, America did still deploy them to the Pacific, 6 divisions in total across the entire war, and in May of 1943, the desire for an amphibious tank destroyer was raised.

The concept of an amphibious tank destroyer made a lot of sense. While tank destroyers may not have been generally well received in the pacific, an amphibious one could have cleared up some logistical hurdles for their deployment and could have acted as amphibious fire support for landing forces. Thus, America began building a prototype.

A failed floatation device

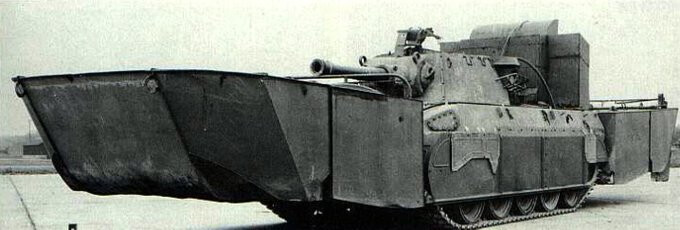

The original plan was to take the T70 GMC (officially the Carriage, Motor, 76mm Gun, T70)—the prototype that became the M18 GMC (officially the Carriage, Motor, 76mm Gun, M18), and attach to it the new T7 Ritchie floatation device, which comprised two large pontoons attached to the front and back that could be jettisoned. In November of 1943, Buick was handed a contract to build a pilot vehicle. The pontoons weighed a combined 7,700 pounds and could be jettisoned by a switch in the vehicle that triggered an electrically fired cartridge that removed a clevis pin holding them to the vehicle.

The pilot was first tested on 29 December, 1943 at the Ford River Rouge Plant. The tests were… rocky. The vehicle demonstrated a swimming speed of 4.2 mph (6.8 kph), but issues were found with the jettisoning mechanism for the floats and the lack of any form of gyrostabilizer made firing while in the water—one of the main uses of an amphibious tank destroyer—difficult. Buick was given the authorization to build four more prototypes with improved versions of the T7 on 1 January, 1944. These new, improved T7 kits featured a new mechanical release that made the jettison mechanism more reliable. Tests were conducted in February and on 16 March, the production of 250 T7 kits was approved. However, none of them would ever be used in combat. An attempt was also made to fit the T7 to the T88 GMC—an M18 fitted with a new 105 mm T12 howitzer—but this too died along with the T88 project in 1944.

The T86 GMC

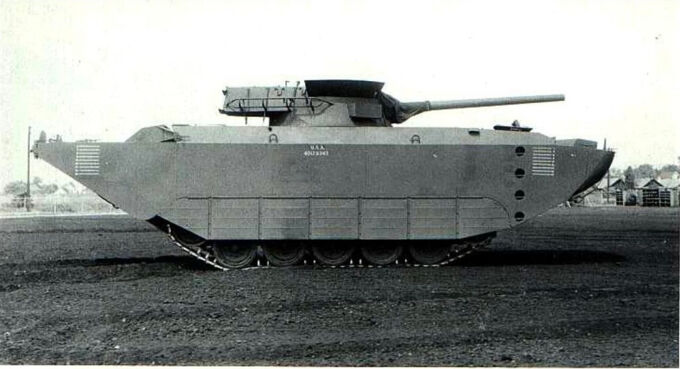

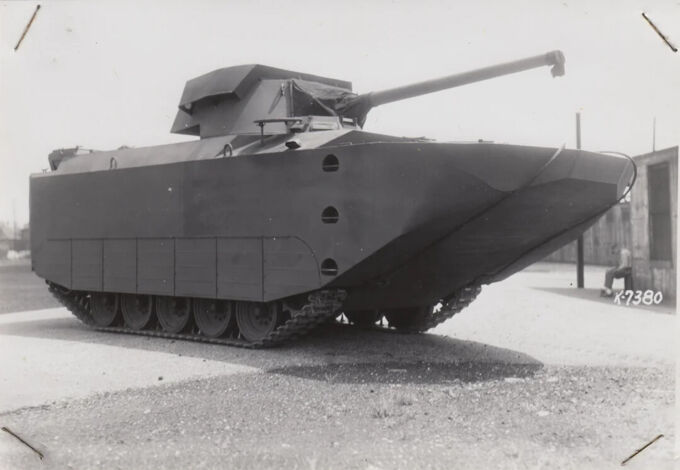

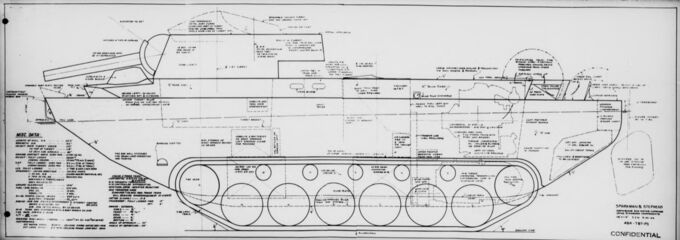

Meetings about the project in December of 1943 and January of 1944 resulted in the conclusion that the T7, while adequate, was far from ideal. Thus, in February, the National Defense Research Committee’s Armor and Ordnance Division initiated the development of the T86 GMC (officially the Carriage, Motor, Amphibious, 76mm Gun, T86). The T86 was derived from the T70 + T7 combination project, but it was distinct.

The T86 was based on the production M18 and instead of using the T7 Ritchie pontoons, the T86 used a new, lighter system meant for it. Unlike the T7 which could be jettisoned, these were fitted more permanently. The system could still be removed, but they were not easily jettisonable like the T7 was. This new tank also saw the addition of a single-plane vertical gyrostabilizer which finally allowed it to accurately fire on the move while in the water.

Additionally, another prototype—the T86E1—was built. The T86 used just tracked propulsion in the water. However, the T86E1 had 2 propellers in the rear for amphibious propulsion. There was also a plan for the T87 which would have been the same, but with a 105 mm howitzer. However, the Army chose to delay the construction of the T87 until the T86 and T86E1 had undegone trials to determine which amphibious propulsion mechanism was better.

Modifications and improvements

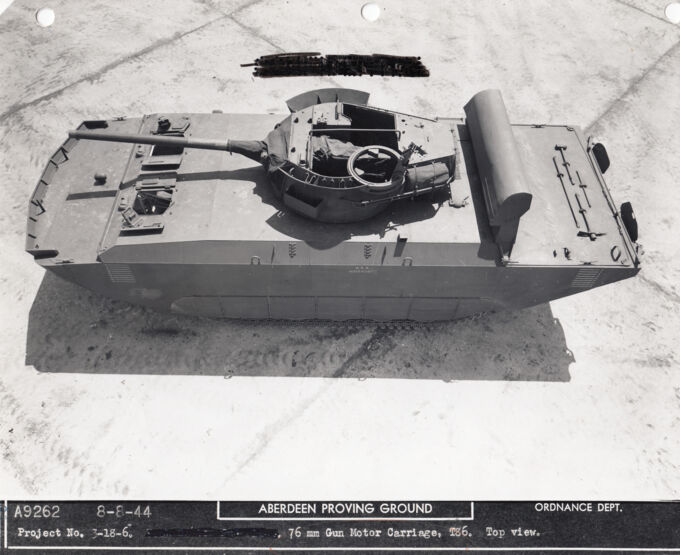

On 10 August, 1944, the T86 began its testing at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland as well as in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. During the tests, some modifications were made to the vehicle. The most major of them was the addition of a new steering station, primarily for use in the water, situated just forward of the turret. This new steering station had the same seat as the driver’s seat in the M18, track steering levers, a foot-operated throttle, and a wheel to control the vehicle’s rudder. It also had an experimental gyro-compass installed, though in rough waters it did not provide accurate readings. This new driving station also required a dome light to be moved and rewired.

The tests also trialed 3 different cupola arrangements for the driver. One was the commander’s cupola ripped straight from the M24 Chaffee with 5 vision blocks spaced by 60º (measured from the center of the cupola to the center of the vision block), another was a cupola with view provided through three 8-inch periscopes which provided 27 feet of view, and the third was a lighter cupola designed to combine the vision of the M24's cupola with the low profile of the periscope cupola. It featured 5 vision blocks spaced by 55º and provided 46 feet of view. It was especially advantageous when the waterline was only 12 inches-or-so below the rim of the bow and when the waves were small enough that what was beyond them could be seen, though this was only a minor consideration because most water driving would be handled by the third, central steering station and the height of the periscopes was useful for land driving. Only the M24 cupola configuration provided a hatch for the driver in the cupola. A 4-inch periscope cupola meant to increase the transverse field of vision for the driver compared to the 8-inch periscopes with a vision range roughly equal to that of the 5 vision block cupola was also considered. The 8-inch periscope was also modified during trials, repositioning the periscopes 2 inches forward and 2 inches outboard to better the driver’s view.

Several other modifications were made too. The forward corners of the deck trunk were cut off and replaced with 2 vision ports to increase driver visibility. 2 different positions were tried, one on each block, and it was found that the more forward position used on the vision port closer to the driver’s side provided better visibility. These vision ports also necessitated the sockets for the headlights being moved inward and rewired. Several rudder configurations were also tested, with a relatively large rudder found to be most effective due to the vehicle’s size and slow swimming speed. The rudder controls were also reworked. Originally controlled by a spool and crank, the mechanism was replaced by 2 steering wheels and a steering box taken from a Jeep. One steering wheel was placed in between the driver and co-driver for equal access and the second was placed at the third driving station. Each wheel’s upright spoke was painted to give an indication of the rudder position and access to the first wheel was improved by moving the track control rods from the overhead position to the driving compartment’s floor. Additionally, the forward deck was strengthened with stiffening rings and the siren was moved 3 inches aft to not interfere with the gun’s depression angles, though this new position was more exposed.

In terms of safety, many small changes were made:

- The priming line was enlarged to extend out from the hull to avoid a buildup of mud.

- Metal shrouding was provided for many open regions of the vehicle to avoid discarded shell casings falling into moving parts.

- Access to the bottom escape hatch was improved through the moving of the carbon dioxide system that was used for firefighting to reduce obstruction and adding a light to illuminate it.

- New hatches for the driver and co-driver were added that had reduced wear and a more effective quick release mechanism.

- A new stack cap for the exhaust was fitted. The stack cap is the piece on top of the tower that raises over the exhaust on the engine deck to direct the exhaust upwards and shield it from water when swimming. The new stack cap directed all of the exhaust backwards instead of the previous arrangement in which part of the exhaust was directed forward which caused recirculation of the gasses through the turret when in the water. Both stack caps limited gun depression over the rear, but the new cap limited it slightly more.

- A new channel was added running perpendicular to the vehicle’s centerline. This channel connected to the tip of the exhaust stack cap to prevent deterioration from engine heat. The channel was sealed with several layers of asbestos. While intended to be a safety measure, this was actually dangerous because, though unbeknownst to the designers of the T86, asbestos causes cancer.

- The frames around the turret had air louvres added to allow for the passage of engine air which, during swimming, was pulled through the turret.

- The drain holes from the bow cell to the main hull were enlarged to prevent clogging.

- The surf shield was strengthened to protect it from muzzle blasts.

The engine also had a couple changes too. The screen that engine cooling air passed through when in water was replaced with a new, less obstructed one. Meanwhile, the differential’s ring and pinion gears were upgraded which provided the engine 26% greater torque compared to the M18's, and with this, the torque converter release values were changed to prevent excessive pressures. Thermocouples were also added for temperature testing, though they were later removed. Furthermore, the vehicle’s uneaven ground clearance was fixed by removing one serration on each of the first and second torsion bars which made clearance even within 1/8 of an inch (0.3 cm).

August tests

The T86 was tested from 10 August to 31 August. The following is a list of the test dates and their purpose:

| Test date | Test location | Test purpose | Miles traveled |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Rehearsal for tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 15 miles (24.1 km) |

| 11 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Firing tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 5 miles (8 km) |

| 12 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Steering and general performance tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 4 miles (6.4 km) |

| 14 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Firing tests | Land: ? Water: ? |

| 18 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Cooling, vision, and steering tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 5 miles (8 km) |

| 23 August, 1944 | Rehoboth Beach | Surf and vision tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 2 miles (3.2 km) |

| 24 August, 1944 | Rehoboth Beach | Surf, vision, sand, steering, and rough water tests | Land: 3 miles (4.8 km) Water: 3 miles (4.8 km) |

| 31 August, 1944 | Aberdeen | Steering, vision, and bilge pump tests | Land: 2 miles (3.2 km) Water: 6 miles (9.7 km) |

Note: The distance traveled and potential additional purposes of the 14 August testing date are not known because the report does not describe this testing date in the list of testing dates, but instead only mentions it when describing the firing tests.

Cooling tests

The cooling tests were performed to determine 2 things: cooling of the turret and cooling of the engine. Turret cooling tests were meant to determine the effect of the turret canvas cover on the turret cooling when in the water. This was done in the water because it was during swimming that the engine gasses were routed through the turret. This was the entire reason the new, rearward-facing stack cap was added. Tests found the difference in temperature with and without the canvas turret cover to be negligible.

Engine tests found another cooling issue. The running temperature for the engine oil was 5-10º F hotter than the safe limit stated by the manufacturer. It was determined that, though a change on the pilot vehicle was not warranted, it would be a serious flaw in the production vehicle unless addressed. All other engine cooling tests went well. Oil temperatures in the torque converter and differential were very low and the cylinder head temperatures were normal to below normal in cases where excess bilge water from the after compartment was being picked up and blown onto the lower right cylinders.

Steering tests

In the water, steering ability was found to be greatly aided the third steering station. The third steering station was found to be effective in allowing the driver to maintain a steady course even when spray from rough waters or surf was being thrown onto the vision ports of the other 2 drivers. It was also found to allow the driver to determine exactly when the vehicle began to turn while still having clear all-round vision—something difficult for the other 2 drivers due to their sights concentrating their vision primarily forwards, though the third driving station was still only a partial solution.

The rudders were found to have issues, however. The attempt to balance them was found to cause the vehicle to oversteer. Balancing a rudder is designing it so that the center of pressure exerted on the rudder by the water when the rudder is deflected is aligned with the rudder’s axis of rotation. The benefit of a balanced rudder is that it requires less torque to steer the vessel. In the T86, the rudder was balanced because the lesser torque requirement would help relieve mechanical stress, but it caused the issue of oversteering and was noted to be a mistake.

Vision tests

The vision tests found a couple of issues. One of them was that the surf shield made the driver’s forward vision block entirely useless as even its stored position still blocked it. Another issue was found when going over hills. The grade of a hill is how many feet the hill rises per every 100 ft (30.5 m) of horizontal distance (e.g. 10% grade is 10 ft (3 m) up for every 100 ft (30.5 m) forward). On hills of greater than 30%-50% grade, the driver was completely blind in the forward direction and could not see at all to the other side due to the length of the bow. In these circumstances, the driver actually had to climb out of the hatch and onto the bow to look forward and see what was ahead. The test report noted that even limited vision would be a significant improvement.

The vision ports on the forward corners of the deck trunk were effective. They were roughly 2 inches too high for land driving and a little too far out for the drivers to take full advantage of them, but they were nonetheless effective.

Surf, rough water, and sand tests

Surf tests went more or less exactly as hoped for. The vehicle performed as desired with no design issues, though the bilge pump that had been steadily wearing down for a while did finally break with the sprocket chain jumping the sprocket because the chain had been misaligned and that wore down the teeth over time. However, before it broke, it too was functioning as desired.

Rough water tests—an opportunity brought about by strong winds on the second day of testing in Rehoboth Beach—also went well. Waves started at 3 ft (0.9 m) tall and only got worse from there, but the vehicle handled it well. It handled the waves, the drivers and crewmembers were more or less comfortable, and the drivers' vision was never completely blocked, especially from the third driving station. The only issue was that the hatches turned out to not be watertight which is really, really funny.

Finally, sand tests also went well. The 21-inch (53.3 cm) tracks had no problem on sand with no noticeable digging behavior. Even on dunes of 30%-50% grades, the vehicle crossed them well with functionally negligible digging behavior, though the dunes' grades did create the aforementioned vision issues.

Firing tests and other findings

Firing tests on the ground went well, but the water tests were a more mixed bag. 2 months before these tests, the T86 had performed firing tests at the same site and firing range. From 2,300 yards (2,103 m), 3–4 shots fired in succession were all hits. However, this time, from a distance of only 1,500 yards (1,371 m) at maximum and closing as low as 800 yards (732 m) and with calmer seas (waves of roughly 1 ft (0.3 m) from crest to trough), the firing accuracy was very low. Every shot except the first fired too high and the gunner claimed that the stabilizer was not keeping up with the vehicle’s rolling in the waves. Those in charge of the testing attributed this to the gunner’s inexperience.

The gunner also reported a lot of friction in the turret traverse and stabilizer. This was found to be due to corrosion, an issue which would need to be addressed. This almost certainly also contributed to the poor accuracy during the firing tests on 14 August.

The only other issues noticed were that there was a lot of water and oil buildup in the space between the main hull fashioned out of what was left of an M18 hull and the pontoons attached to it, and that accessing the engine for maintenance was quite difficult.

Additional recommendations

From these tests, a series of additional recommendations were made. These recommendations were:

- A hatch aft of the engine should be added for maintenance access as well as a carbon dioxide release.

- The cable shelves and turnbuckles would need to be made heavier if the suggestion of unbalancing the rudder was followed up on.

- New roof hatches for the driver and co-driver as well as 2 side escape hatches for them just aft of their seats should be added.

- The generator should be moved aft to avoid getting wet when spray entered the turret.

- The master switch box should be repositioned so the driver can more easily reach it.

- The instrument panel should be made waterproof and moved to a position where both drivers could see it.

- 4 boarding ladders should be added, 2 on each side, 1 near the bow and one by the stern.

- The stowage compartments, particularly ammunition stowage, needed to be rearranged.

- The forward end of the vehicle had to be strengthened.

September-October tests

That’s right, there’s more! From 26 September to 5 October of the same year, more tests were conducted in Fort Ord, California. These test results are, thankfully, much shorter.

General water tests occurred on a 4 mile (6.4 km) course with waves of 3-4 ft (0.9-1.2 m) and an additional wave chop of 1 to 1 and a half feet. Rolling from side to side never exceeded a maximum of 20º and pitch front to back never exceeded 10º, engine oil temperature peaked at around 225º F (107.2º C), and fuel consumption was around 6 gal/mi (30 gal/hr). The results were generally very favorable, the only issues being the unsatisfactory engine cooling—a stark contrast to the previous tests, excessive noise, and high fuel consumption. All but the latter were deemed fixable.

Water speed and maneuverability tests too went well. Average forward swimming speed was 5.16 mph (8.3 kph) and reverse was 3 mph (4.8 kph), with saltwater speed being slightly lower than freshwater speed, likely due to the greater density of saltwater, and the theoretical max reverse speed being 4 mph (6.4 kph). Rudder steering only provided a turning circle of 33 ft (10.1 m), track steering yielded 75 ft (22.9 m), and both combined produced 23 ft (7 m). This was considered acceptable. Finally for the water trials, surf tests went well too. The vehicle performed very well, never rolling or pitching too much, breaking waves, and generally staying course in surf as high as 10 ft (3 m).

On land, the vehicle performed as desired. Turning radius was 35 ft (10.7 m) from both drivers' stations and the vehicle never pitched above 35% grade in soft, dry sand. It was also able to get onto the beach well from the water in every instance. Those tests were conducted with a beach grade of 20%.

When compared with the LVT(A)(4), the army’s primary amphibious landing support and assault vehicle in use at the time, the T86 exceeded its performance in every single aspect, both on land and in the water, except for top forward speed in rough water.

The additional, non-maneuverability-focused tests did not go as well. The gun held on target, the surf plate shed water as desired, though the deck’s construction already did most of the work, the stack cap effectively stopped water from entering the engine, and the electric bilge pump was found to be effective. However, the turret’s canvas cover was insufficient as it let too much water in, the chain-driven bilge pump was unreliable, the engine ran too hot, with an improved air inlet pan and repositioned engine oil cooler both being recommended, the hatch seals were not fully watertight, the carbon dioxide fire fighting system was ineffective at putting out fires, and the stowage was difficult to access. Despite the prior test report finding that the third steering station greatly improved visibility and vehicle handling in the water, the test report for this round of tests recommended its removal on subsequent pilot vehicles to improve stowage accessibility.

Overall though, the vehicle was found to be satisfactory. The assessment was that any of the remaining issues could be worked out rather easily.

During these tests, 4 track designs were tested (tracks “A” through “D”). The most effective was the “B” track. The “B” track was a cast steel, 21 inch (53.3 cm) wide track modified from the M24's tracks with a new grouser (the structure on the track’s metal plate that aids in providing traction) that featured an outwards-facing wing extension cast as part of it, as well as weight-saving holes in the base track plates.

The T86E1 GMC and T87 HMC

There is still more though. The T86 GMC was the first pilot, but 2 more were built. Pilot No. 2 was the T86E1 GMC and Pilot No. 3 was the T87 HMC. The T86E1 was nearly identical to the T86, except for it using propeller propulsion instead of track propulsion in the water. These propellers were 26 inch (66 cm) screws run in tubes to a rear transfer case. They sat right behind the twin rudders. Track propulsion was found to be the superior method, though track steering when used without rudder steering was still noted as unsatisfactory and the screws did increase the swimming speed to 6.2 mph (10 kph). Additionally, the T86E1 was a foot shorter than the T86—28 ft and 3 inches (8.6 m) instead of 29 ft and 3 inches (8.9 m)—though test reports did propose that it be lengthened to 29 ft and 7 inches (9 m). Its cruising range in the water was also rated as 10 miles (16.1 km) less than the T86—60 miles (96.6 km) instead of 70 (112.7 km)—and it weighed 46,600 lbs (21,137 kg) which was 1,600 lbs (726 kg) heavier than the T86, though a proposed modification would have reduced that weight to 46,000 lbs (20,865 kg). One proposed modification would also have increased its cruising range on land and in water by 25 miles (40.2 km) each to 175 (281.6 km) and 85 miles (136.8 km) respectively.

Unlike the very similar T86 and T86E1, the T87 HMC (officially the Carriage, Motor, 105mm Howitzer, T87) was much different. The biggest difference was that, instead of the 75 mm M1 cannon sitting in a T1 mount that was present on the T86, T86E1, and the common ancestor M18, this vehicle featured a 105 mm T12 howitzer taken from the T88. In fact, the entire vehicle was almost more T88-derived than it was M18-derived, especially given that its hull was even shorter than the T86E1 at 27 feet and ¾ inches (8.2 m). The 12.7 mm M2 machine gun was also repositioned and one fit of it seems to have had twin 7.62 mm machine guns with a combined 5,000 rounds instead of the M2 with 1,000 rounds. Furthermore, its weight returned to the 45,000 lbs (20,412 kg) of the T86 and its land cruising range increased to 175 miles, the same as the proposed range on the T86E1, though the water cruising range reduced to 40 miles (64.4 km).

The T87 incorporated many of the improvements recommended from the T86's and T86E1's testing such as more outboard side vision ports, front panel periscopes, and a waterproofed engine and electrical systems.

All 3 vehicles were rated for inclines of up to 60% grade.

Though all of the prototypes had centrally-mounted turrets like the M18 and T88, a rough design was drawn up for a potential frontally-mounted turret that could have aided in gun depression, though it had the potential to make the vehicle very front-heavy which could have been quite dangerous for an amphibious vehicle. This may have been why this proposal was never followed through on.

Why was the project killed?

The T86 and T87 projects had been progressing well and were looking promising. However, nothing could save the project from factors beyond its control. On 15 August 1945, Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan to the Allies and it was formally signed on 2 September. The war was over and America was shifting its attention towards Europe and the USSR. The T87 was still in testing, but the M18 was already obsolete in the US military. The gun was not up to the standards of more modern ones, the open top nature posed danger to the crew, better equipment was rapidly coming along, and US tactical doctrine was shifting away from light, fast tank destroyers. The M18 was gone from US service by the end of 1945. The T86 and T87 were slower, larger, more cumbersome, amphibious versions of a vehicle America did not need as it was preparing for a hypothetical European war that would not be fought with amphibious fire support. Soon after the end of WWII, the project was killed.

References

- Harold_Biondo. “T86 and T86E1 76mm GMCs — Amphibious Hellcat.” Reddit, 2025.

- Hecker, Lawrence G. “Amphibian Based on 76mm Gun Motor Carriage M-18.” Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, Division 12-Transportation, 1944.

- Hecker, Lawrence G. “Amphibious 76mm Gun Motor Carriage, T-86. Report of Landing Vehicle Board Trials at Fort Ord, California.” Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, Division 12-Transportation, 1944.

- Nuttall, Clifford J. “Report on Tests and Modifications on the Amphibious 76mm Gun Motor Carriage T-86, in the Period August 10, 1944 to September 1, 1944 at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Maryland and Rehobeth Beach, Delaware.” Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, Division 12-Transportation, 1944.

- Williamson, Mitch. “76mm Gun Motor Carriage T86, T86E1, and T87 (Amphibious) — War History.” War History, 2020.