In 1943, the Japanese recognized an imminent threat on the horizon: the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Development of this powerful bomber had begun in 1939, and the Japanese were certain it would eventually be deployed against their homeland. However, they faced a significant challenge—they lacked an effective way to counter the B-29 and feared they wouldn’t have a solution ready in time. The answer to this problem came in the form of one of the most innovative interceptors ever to see operational use.

Japanese representatives in Berlin

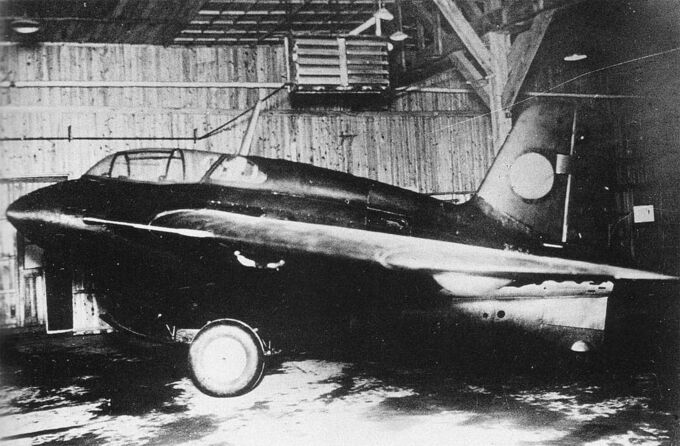

By mid-1943, Japanese military representatives in Berlin were informed about the progress of the Messerschmitt Me 163, a rocket-powered point-defense interceptor. Their interest was immediate. Soon after, military attachés from both the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army visited Bad Zwischenahn, Germany, where Erprobungskommando 16 (EKdo 16) was based. This unit, established earlier in 1943, was tasked with developing combat tactics, deployment strategies, and training for the Me 163, as well as coordinating efforts between contractors and test centers involved in its production.

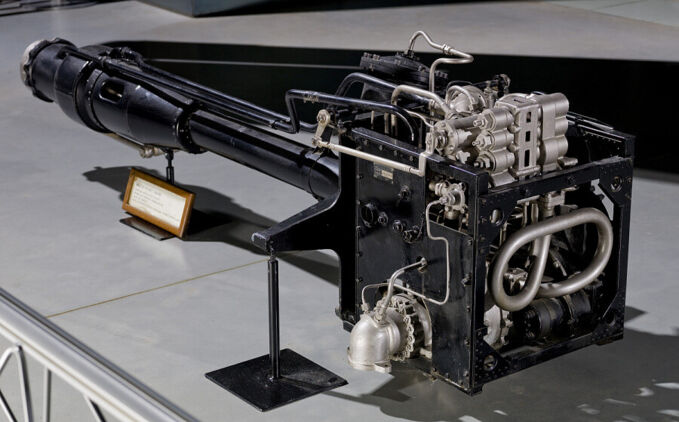

During the visit, EKdo 16 personnel explained the challenges of the Walther HWK S09A rocket engine, including its temperamental nature and the hazardous, explosive properties of the two fuels it used. However, these warnings did not deter the Japanese. They saw the Me 163’s ability to climb rapidly and achieve incredible speeds as the perfect solution to their defense needs, outweighing any concerns about the engine or fuels. Without hesitation, the Japanese began negotiations to acquire the Me 163B.

Not everyone agreed on the value of the Me 163. While detailed reports from the Japanese attachés in Germany were generally positive, some raised concerns. They argued that producing the specialized fuels needed for the aircraft in sufficient quantities to meet operational demands would be difficult. Others criticized the Me 163’s unconventional design, suggesting that developing the aircraft and its engine would consume vital resources. Despite these objections, the proponents of the Me 163 ultimately prevailed.

Negotiations

The Japanese quickly and successfully negotiated licenses to produce both the Me-163B aircraft and its HWK S09A rocket engine, paying 20 million Reichsmarks for the engine license alone.

As part of the agreement, Germany committed to providing full blueprints for the Me 163B and the HWK S09A, detailed manufacturing data for both, one fully assembled Me 163B, three HWK S09A engines, and two sets of subassemblies and components, all to be delivered by March 1944.

Additionally, the agreement stipulated that Japanese military attachés in Berlin would be informed of any improvements to the Me 163 design so they could incorporate updates into their version. The Japanese also requested permission to oversee the manufacturing processes for both the aircraft and the engine, as well as to study and review Luftwaffe operational procedures for the fighter.

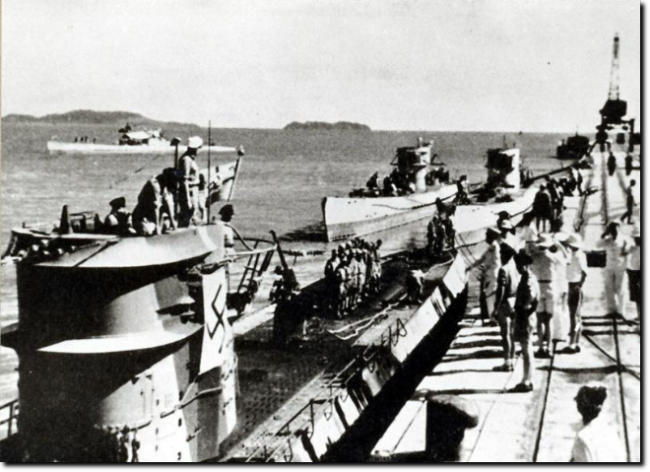

German submarines U-511 and U-1124

The submarine U-1224 was built by Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, with its keel laid on November 30, 1942. It was commissioned on October 20, 1943, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Georg Preuss. Initially assigned to the 31st U-boat Flotilla for training, U-1224 was intended from the start to serve as a training vessel for Japanese sailors.

This submarine became part of the technological and tactical exchange between Germany and Japan during World War II. The plan involved training a full Japanese crew to operate a U-boat, after which the submarine would be transferred to Japan. This initiative was led by Vizeadmiral Paul Wenneker, the German naval attaché in Tokyo, who supported sharing German submarine expertise with Japan. In August 1943, Lieutenant Commander Sadatoshi Norita and a 48-man Japanese crew traveled to Germany after arriving in France aboard the Japanese submarine I-8. They began their training with German sailors in the Baltic from October 1943 to February 1944.

U-1224 was the second German submarine designated for transfer to Japan, following Adolf Hitler’s 1943 decision to send two U-boats to aid in disrupting Allied shipping in the Indian Ocean. Although Großadmiral Karl Dönitz opposed the idea, citing the need for U-boats in the Atlantic and concerns over German-Japanese crew relations, Hitler’s decision prevailed.

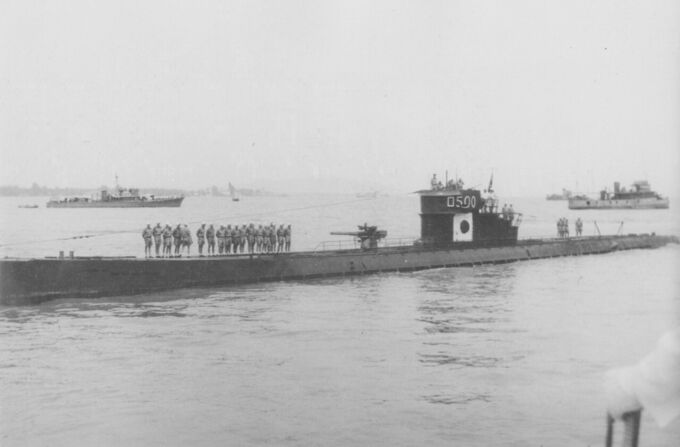

After completing three months of training, U-1224 was officially recommissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy as Ro-501 on February 15, 1944. Lieutenant Commander Sadatoshi Norita was appointed as its commanding officer. The Japanese crew gave the submarine the nickname “Satsuki No. 2” and continued their training at the U-boat anti-aircraft school in Swinemünde from late February to late March 1944. Ro-501 was slated to join the 8th Submarine Squadron, stationed in Malaysia.

Marco Polo I

The first submarine, U-511, code-named “Marco Polo I,” left Germany in May 1943. Its German crew transported supplies, engineering officers, and key passengers, including Japanese naval attaché Naokuni Nomura and diplomat Ernst Woermann, to Penang, Malaysia. After unloading supplies for the Indian Ocean-based Monsun Gruppe, U-511 arrived in Japan, where it was commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy as Ro-500. U-1224, similarly designated as “Marco Polo II,” followed in this exchange program.

Transport and renaming of German Submarines

Three submarines—Ro-500, Ro-501, and I-29—were assigned to transport materials to Japan. The Ro-500, still in service under the Kriegsmarine as U-511 at the time, departed from Lorient, France, on May 10, 1943, en route to Penang, Malaysia.

Onboard were four Japanese passengers, including Vice Admiral Naokuni Nomura and Major Tamotsu Sugita of the Imperial Japanese Army Medical Service, as well as data related to the Me 163B.

During the voyage, U-511 was renamed Satsuki I (meaning “May”). It arrived in Penang on July 16, 1943, where Nomura, Sugita, and the other Japanese passengers disembarked and traveled to Japan by air. U-511 left Penang for Kure, Japan, on July 24, 1943, arriving on August 7, 1943. Upon arrival, the submarine was formally transferred to the Imperial Japanese Navy and renamed Ro-500.

The Ro-501, originally the German Type IXC/40 submarine U-1224, was officially handed over to the Imperial Japanese Navy on February 15, 1944. Renamed Satsuki 2 by the Japanese, it was commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy as Ro-501 on February 28, 1944, with Lieutenant Commander Norita as its captain.

On March 30, 1944, Ro-501 departed Kiel, Germany, carrying manufacturing data, blueprints for the Me 163B, and other cargo. However, on May 13, 1944, at 7:00 PM, northwest of the Cape Verde Islands, the USS Francis M. Robinson, a Buckley-class destroyer escort, detected the submarine at a range of 825 yards. The Francis M. Robinson launched a coordinated attack, deploying 24x Mark 10 Hedgehog bombs and five salvos of Mark 8 depth charges. Sonar reported four explosions, confirming the destruction of Ro-501.

I-29

The Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-29 departed Lorient, France, on April 16, 1944, carrying critical technology and components. Among its cargo were an HWK S09A rocket motor, the fuselage of a Fieseler Fi 103, and a Junkers Jumo 004A turbojet, along with various other materials. Onboard were Technical Commander Eiichi Iwaya and Captain Matsui. Iwaya carried blueprints for the Me 163B and Me 262, while Matsui had plans for rocket-launching accelerators. Together, they also transported schematics for a glider bomb and radar equipment.

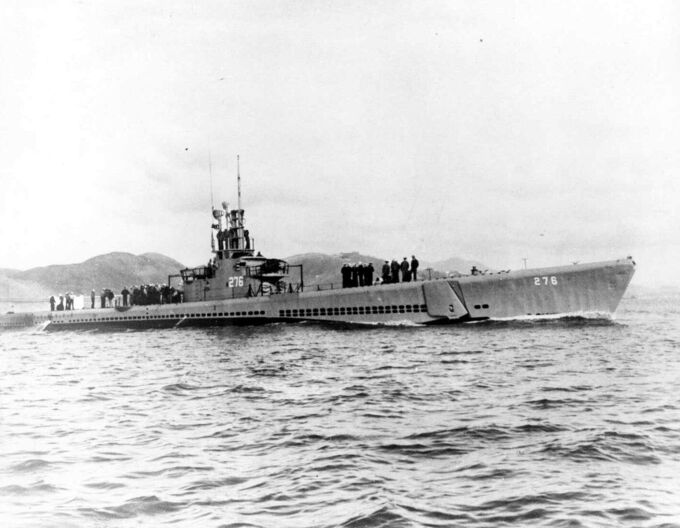

The submarine arrived safely in Singapore on July 14, 1944. There, Iwaya and Matsui disembarked with part of their documents and continued to Tokyo by air. However, Allied codebreakers intercepted a message from Berlin to Tokyo detailing the I-29’s cargo. On July 26, 1944, at 5:00 PM near the western entrance of the Balintang Channel in the Luzon Strait, the USS Sawfish spotted the I-29 on the surface. The submarine fired four torpedoes, three of which struck their target. The I-29 sank almost immediately, with only one survivor, who swam to a nearby Philippine island and reported the loss.

After disembarking from the I-29, Technical Commander Eiichi Iwaya left behind part of the documentation for the Me 163B and Me 262. The loss of the I-29, along with the earlier destruction of Ro-501, dealt a significant setback to Japan’s development program. However, the information that Iwaya had preserved, combined with the data received from Ro-500, was sufficient to keep the project moving forward. In July 1944, the Imperial Japanese Navy issued a 19-shi specification for a rocket-powered interceptor.

This decision was driven by an analysis of the available documentation for the Me 163B, Japan’s current industrial capabilities, and the determination of Vice Admiral Misao Wada, who strongly supported the development of a rocket aircraft. The Imperial Japanese Navy assigned the project to Mitsubishi, which was initially hesitant to take it on. However, further consideration, including the need to adapt the Me 163B design to Japanese production methods, led Mitsubishi to agree.

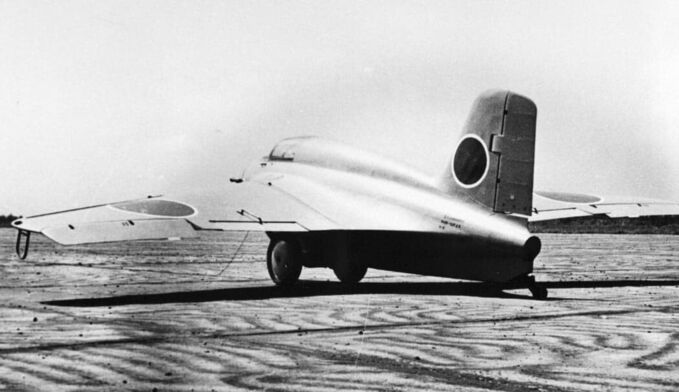

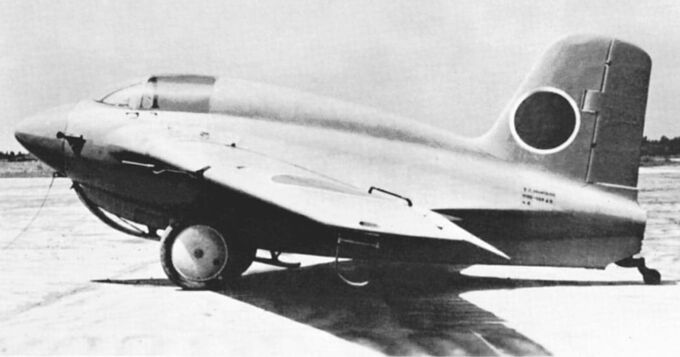

Although the Imperial Japanese Navy spearheaded the project, the Imperial Japanese Army also became involved in the development of both the aircraft and its rocket motor. The resulting Japanese rocket interceptor was named J8M1 Shūsui (meaning “Autumn Water”) for Imperial Japanese Navy use and was designated Ki-200 in Imperial Japanese Army service.

First variant

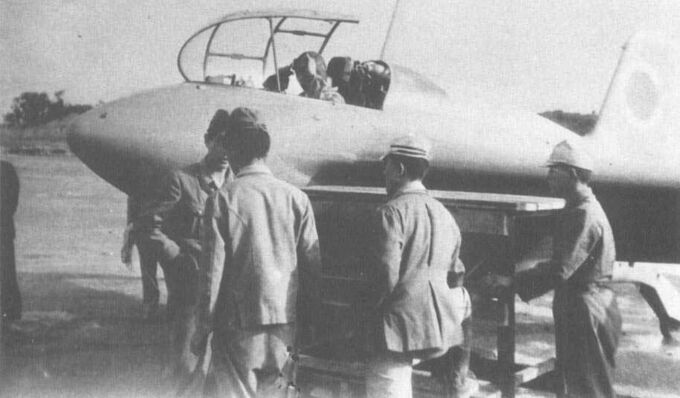

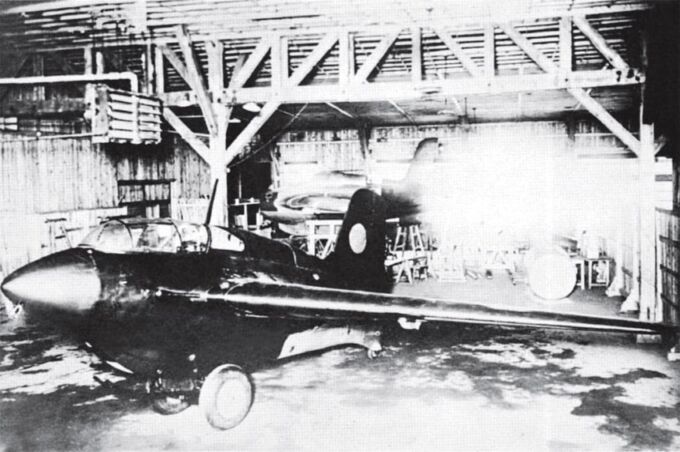

In July 1944, the Japanese Navy issued the 19-Shi specification for the development of a rocket-powered interceptor, assigning the task to Mitsubishi. The project rapidly evolved into a joint venture with the Army, which had plans for its own version. Mitsubishi, led by Otsujiro Takahashi, completed a mock-up by September 1944, which was approved for prototype construction.

To gather data on handling the tailless design and train future pilots, the Navy initiated the development of a glider version, the MXY8 Akigusa (Autumn Grass), at the Dai-Ichi Kaigun Koku Gijitsusho in Yokosuka. The MXY8 was first flown in December 1944 at Hyakurigahara Airfield by Lieut-Cdr Toyohiko Inuzuka, the J8M1 project pilot. The glider demonstrated satisfactory handling, which bolstered confidence in the upcoming powered variant. Additionally, heavier training gliders, designated Ku-13 Shusui, were developed with water ballast to replicate the J8M1’s weight.

Powered prototypes

Mitsubishi began construction of powered prototypes, designated J8M1 for the Navy and Ki-200 for the Army. The first prototype was completed in June 1945 and underwent checks at Yokosuka. The maiden flight took place on July 7, 1945, but the engine failed during a steep climb, leading to a crash and the death of Lieut-Cdr Inuzuka. The investigation identified fuel system flaws that were being addressed in subsequent prototypes when the war ended, halting further tests.

Despite the limited success, the production of J8M1s was underway at Mitsubishi, Nissan, and Fuji. The Navy intended to arm the J8M1 with two 30 mm Type 5 cannons, while the J8M2 Shusui-Kai was designed to replace one cannon with extra fuel tanks for a longer range. The Army prioritized an advanced variant, the Ki-202, as their top interceptor project, but none of these plans came to fruition before Japan’s surrender in August 1945.

- Francillon, René J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam & Company, 1970 (2nd edition 1979). ISBN 978-0-370-30251-5.

- Mitsubishi J8M — Wikipedia

- https://planesoffame.org/aircraft/plane-J8M1

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/U-Boot-Klasse_IX

- https://www.cdvandt.org/Tel-data-S406S.pdf

- https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/messerschmitt-me-163b-1a-komet/nasm_A19530072000

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “The Type IXC/40 boat U-1224”

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2017). “IJN Submarine RO-501 (ex-U-1224): Tabular Record of Movement (Revision 4)”. combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_submarine_U-1224

- https://dubm.de/the-voyage-to-the-far-east/?lang=en

For Pictures:

- https://testpilot.ru/japan/mitsubishi/ki200/

- https://www.airwar.ru/enc/fww2/j8m.html

- https://planesoffame.org/aircraft/plane-J8M1

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Mitsubishi_J8M

- https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/messerschmitt-me-163b-1a-komet/nasm_A19530072000

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2017). “IJN Submarine RO-501 (ex-U-1224): Tabular Record of Movement (Revision 4)”. combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_submarine_U-1224

- https://dubm.de/the-voyage-to-the-far-east/?lang=en