Chaff (also known as “Window” in World War II) are small strips of radar reflecting material (aluminium, metallized paper, fiberglass or metallized polymer based films) that are released in large quantities by an aircraft’s countermeasure dispenser which create a cloud of false radar targets.

Game Usage

Introduced in Update 2.5 “Ixwa Strike”, chaff countermeasures are available to almost all aircraft that feature countermeasure dispensers.

Chaff operates in a similar way to flares, creating false signatures which can throw off radar missiles, trigger fuzes, and make aircraft radars lose lock of an aircraft. However, different types of missiles and radars require different deployment techniques in order for chaff to be effective.

Against Pulse radars and missiles, simply dropping chaff is often enough to cause them to lose lock of your aircraft. While there are some aircraft that use Pulse radars with chaff rejection systems, those systems are easy to defeat by simply reducing the closure rate of your aircraft to them.

Defeating Pulse Doppler radars and missiles is a bit more difficult. Pulse Doppler radars detect the closure rate of an aircraft so chaff will be rejected as a target in most cases. In order to defeat this type of radar, you need to make your aircraft’s closure rate be as close to zero as possible. This can be achieved by turning to 90 degrees from the radar source in any direction (vertically and horizontally), known as “notching”. If done correctly, the radar will not be able to tell the aircraft apart from the ground or any chaff that is released.

Chaff launch can be performed with either the “Fire countermeasures” keybind which releases the selected pattern of countermeasures (both flares and chaff by default) but also using the “Fire chaff” keybind to only drop chaff. It is possible to use the Weapon Selector menu to choose between firing a mix of both flares and chaff, only flares and only chaff when using the “Fire countermeasures” keybind.

Chaff development and usage

Radar technology which allowed for the detection of aircraft long before they could be seen or heard had already began development in the late 19th century, with more and more countries gradually starting to participate in its development. The USA, USSR, Great Britain, Germany, France, Japan and many others were some of the most notable pioneers of radar at that time.

They were interested in radar for many reasons, primarily military ones. For example, it could be used to detect ships even through fog at sea. The need for detecting aircraft was also becoming more and more pressing with the rapid advancements in aviation and the success of aircraft in World War I that left no doubt their use would increase in following wars.

Due to such high interest in this technology, the first industrial prototypes of both stationary and mobile radar stations began to appear in the second half of the 1930s and because of that, the need to counter these new systems became a necessity.

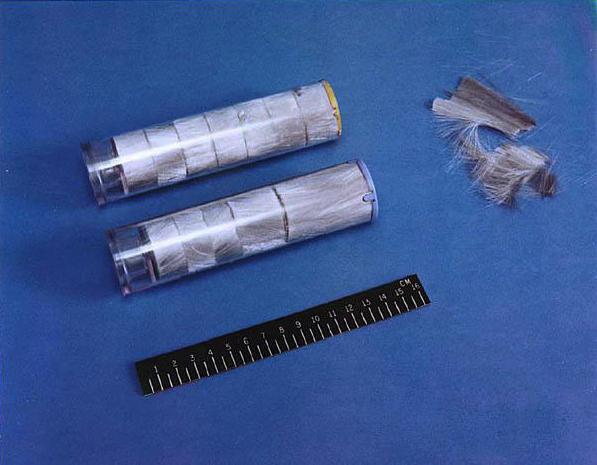

The primary way of decoying a radar emitter is by jamming it using a separate emmitter. However, while this method may be effective, it is complex, dangerous and most importantly, very expensive. Decoying a radar using its own emissions was proposed in the 1940s as a simpler and cheaper solution. By dropping a large number of aluminium strips from an aircraft, the length of each strip being about equal to half the radar’s wavelength, they can be made to reflect the radar signals in a very similar fashion to the aircraft itself, creating multiple false blips on the radar operator’s screen which are virtually indistinguishable from the blip of a real aircraft.

The idea of creating such decoys was initially dubbed “Window” and was proposed in 1942 by British physicists R.V. Jones and J. Curran. In 1943, this new type of countermeasures was for the first time used en masse during the bombing of Hamburg with astonishing results. The radars of German fighters and anti-aircraft guns were overwhelmed by the decoys and were completely unable to distinguish the bomber formations from them. As a result, only 12 of the 791 American and BRitish aircraft were shot down on the first night, while Hamburg itself was left in ruins by the raid.

Although such a large-scale use of radar decoys took the Germans by surprise, this technology was no secret to them as a similar type of countermeasures called “Düppel” was in development by German scientists. However, even though both sides not only knew about the advantages of using radar decoys, a very peculiar situation arose where their use was very sporadic, fearing that if one side used them, the other would respond in kind, leaving them with no ability to counter.

Today, such decoys are most commonly referred to as chaff. While their operating principle remains the same almost a century later, their design has evolved. Modern chaff are primarily composed of lighter aluminum-coated glass fibers, allowing them to linger in the air for longer and therefore jamming radars for a longer amount of time. Their use has also expanded outside countering ground-based radars, being used against aircraft radar systems as well as being used to protect against radar homing missiles. Radars however have not lagged behind, with modern radars using the Doppler effect to measure the speed of objects, they can easily distinguish between a slowly decending chaff cloud and a rapidly approaching aircraft. Therefore, modern chaff reflectors are only effective in conjunction with other airborne defenses and on their own are no longer as significant of a hindrance to radar as they were to early radar designs during World War II.