Aerial Infrared Countermeasures also known as “flares” are pyrotechnic devices that produce a powerful signature within specific wavelengths. When a flare is detected within the FoV of an IR Guided missile, the stronger signture of the flare will cause the missile target it instead of the aircraft that launched it.

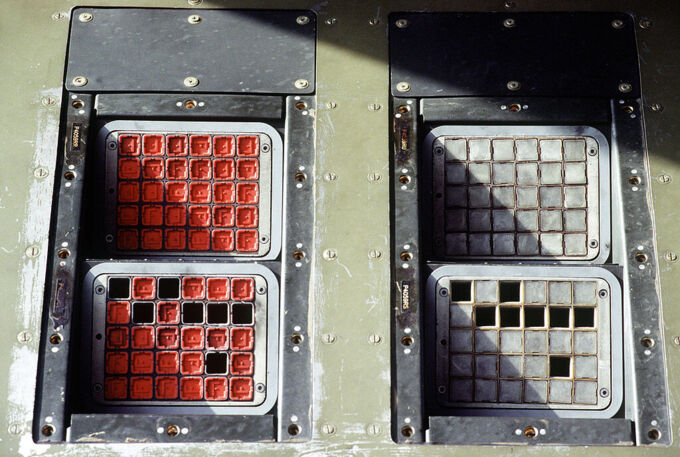

Flare cartriges are usually housed in special devices called “Countermeasure Dispensers” which can individually ignite and launch the flare cartriges once an electrical signal is sent to them. On more modern aircraft, systems like the RWR and MAW can independently control the dispensers, automatically firing off countermeasures when a threat is detected.

The flares cartriges consist of two parts. A smaller pyrotechnic cartridge or gas generator which is used to eject the flare from the dispenser while the flare itself is a larger special pyrotechnic charge, usually composed of magnesium or any other metals with high combustion temperatures which exceed the aircraft’s exhaust temperature.

Tactics and in-game uses

Due to their nature, IR guided missiles are very hard to detect. Only helicopters and modern jet fighters are capable of detecting this type of missile utilizing either IR sensors which detect the missile’s rocket motor or radars which detect the incoming missile’s radar signature.

When a missile launch is detected, it is crucial to deploy flares as soon as possible in order to distract the missile from the aircraft’s own IR signature. The closer a missile is to an aircraft, the harder it is for it to be defeated using flares as not only do the flares require some time to reach their maximum heat output after launch but the aircraft also appears larger than the flares.

In the game, there are three types of flares with each having its own strengths and weaknesses. BOL flares sacrifice effectiveness for quantity while Large Caliber Flares sacrifice quantity for effectiveness.

| Type of Flare | Burn Time | Luminosity |

| BOL Flare | Very Short | Low |

| Regular Flare | Long | Medium |

| Large Caliber Flare | Long | Very High |

After launching flares, it is advised to turn off the aircraft’s afterburner and try to point the engine’s hot exhaust nozzle away from the incoming missile. Disabling the afterburner significantly decreases the aircraft’s IR signatures and pointing the exhaust away from the missile creates a smaller IR signature, making it more likely the missile will follow the flares instead.

Many modern missiles however use Infrared Counter-Countermeasures which significantly reduce the effectiveness of flares. These systems will either shrink the missile seeker’s field of view to reduce the chance of flares appearing inside of it or temporarily pause guidance when flares are detected within its field of view in order to minimize the chances of the missile being defeated by flares.

The creation of flares

Early experiments and the birth of heat-seeking threats

The idea of using heat as a guidance cue goes back to experiments during and after World War II, but it wasn’t until the electronics advances of the 1950s that practical heat-seeking missiles were realised. The AIM-9 Sidewinder is the classic example: introduced in the mid-1950s, it showed how deadly and reliable infrared guidance could be in combat. Once seekers proved they worked, it didn’t take long for engineers to start thinking about ways to fool them.

The first aerial infrared countermeasures

Early countermeasures ranged from towed decoys to electronic tricks, but the simplest workable idea was a small pyrotechnic flare, essentially a burning heat source thrown away from the aircraft. By the end of the 1950s, prototype flare designs were already being tested. Those first flares were basic, but they validated the concept: if you could put a hotter or more appealing infrared target in a missile’s field of view, you could save the aircraft.

Cold War proliferation and the MANPADS problem

Through the 1960s and 70s, infrared seekers spread around the world, and cheaper, shoulder-fired systems made the threat even more immediate. Weapons like the early Soviet MANPADS meant helicopters and transport aircraft that operated low and slow suddenly became tempting targets. Combat experience from Vietnam to the Middle East repeatedly showed how vulnerable aircraft were without countermeasures, and flares quickly became standard kit for many platforms.

How flare systems matured

From the 1970s on, flare technology improved on two fronts: what the flare burned, and how it was thrown. Chemists developed compositions that burned at different temperatures and spectral bands to be more attractive to seekers, while engineers built dispensers that could eject flares in timed sequences and at different angles. That combination, often tied into sophisticated missile detection and warning systems, allowed a more convincing and controlled thermal “scene” to be created to confuse incoming missiles.

The continuing role of flares

Today, flares are still widely used because they’re cheap, simple, and effective against older or simpler seekers. However, as missile seekers also continue to evolve, their role is increasingly one part of a layered defense: flares, radar/IR warning systems, and where possible, active DIRCM. Modern challenges imaging seekers, multispectral discrimination, and smarter signal processing have pushed research into multispectral pyrotechnics and other decoys, and into ways to protect civilian aircraft and helicopters from MANPADS attacks.